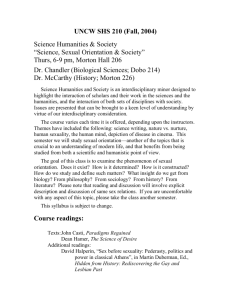

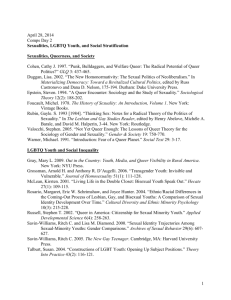

Microsoft Word 2007 - UWE Research Repository

advertisement