Intraoperative Anaphylaxis

advertisement

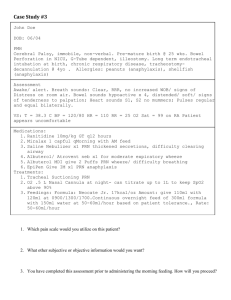

Running head: INTRAOPERATIVE ANAPHYLAXIS Intraoperative Anaphylaxis Angelique I Davis The University of Kansas 1 INTRAOPERATIVE ANAPHYLAXIS 2 Intraoperative Anaphylaxis Anaphylaxis is an immediate type I hypersensitivity response that is difficult to diagnose in the intraoperative setting. Anaphylaxis can present as a multitude of different adverse effects that occur in response to normal induction proceedings (Norred, 2012). “Immediate hypersensitivity reactions occur, however, only once in every 5,000 to 10,000 anesthetics” (Mertes et al., 2010, para. 1). The purpose of this paper is to review the pathophysiologic process of anaphylaxis, identify the signs and symptoms, recognize the common causes of anaphylaxis pertaining to anesthesia, and explore the proper treatment regimen. Type I hypersensitivity is further divided into IgE mediated and non IgE mediated. IgE mediated anaphylaxis is described as allergic and non IgE mediated immune response is defined as anaphylactoid. In the perioperative setting differentiating between the two is difficult; the focus of this paper will be on IgE mediated anaphylaxis (Norred, 2012). The pathophysiology of a type I hypersensitivity allergic reaction is IgE dependent. An individual is exposed to an antigen, and through innate and adaptive immunity, activates T-cells, B-cells, and produces allergen specific IgE antibodies. After reexposure to the antigen, IgE specific antibodies attach to the surface of the mast cells causing degranulation and subsequent release of inflammatory mediators into the extracellular fluid compartment. The release of histamine, tryptase, proteoglycans, carboxypeptidases, prostaglandin, leukotriene, and platelet activating factor are the cause of the life-threatening symptoms of anaphylaxis (Butterworth IV et al., 2013). Type I IgE hypersensitivity typically occurs immediately due to intravenous administration of induction agents, although an allergic reaction can be delayed for an hour or longer (Norred, 2012). INTRAOPERATIVE ANAPHYLAXIS 3 Due to the array of mediators released, it is imperative that anesthetic providers recognize and treat symptoms of anaphylaxis rapidly. Signs and symptoms for the anesthesia provider to be aware of are the results of mast cell and basophil degranulation. Mast cells are largely located in heart, vasculature, respiratory, gastrointestinal, and integument systems (Norred, 2012). The clinical presentation of surgical patients undergoing anaphylaxis may display early cutaneous symptoms that include pruritus, flushing, erythema, urticaria, or angioedema. Cutaneous signs are difficult to appreciate in the perioperative setting. The difficulty is due to patients being draped and the position necessary for the surgery (Mertes et al., 2010). Typically, the late signs of respiratory distress and cardiovascular instability are, at times, the only symptoms that the anesthesia provider may recognize. Respiratory symptoms that commonly occur are wheezing, hypoxia, hypercarbia, angioedema, and increased peak airway pressures. Cardiovascular symptoms present are hypotension, tachycardia, dysrhythmias, shock, or even death (Norred, 2012). Some of these symptoms can be mistaken for bronchospasm, pain, insufficient neuromuscular blockade, bleeding, or light anesthesia (Jacobson et al., 2001). With respect to symptoms of anaphylaxis, the anesthesia provider must consider the onset of symptoms in relation to allergens introduced to the patient (Mertes et al., 2010). The most common allergens in anesthesia are neuromuscular blocking agents, with emphasis on succinylcholine and rocuronium, followed by latex and antibiotics (O’Donnell, 2014). Causative factors that attribute to a potential latex allergy in the operating suite are the use of latex containing gloves, tourniquets, and catheters. Antibiotics that are of primary concern with anaphylaxis are beta lactams, such as penicillins and cephalosporins. While vancomycin and quinolones are known to cause anaphylaxis as well, they do so to a lesser extent (Ebo, Fisher, Hagendorens, Bridts, & Stevens, 2007). INTRAOPERATIVE ANAPHYLAXIS 4 Anaphylaxis is treated in accordance with the severity of symptoms the patient is experiencing. The severity of symptoms is quantified using the Ring and Messmer severity scale. Symptoms can range from mild cutaneous signs to cardiovascular collapse (Norred, 2012) Treatment of anaphylaxis begins with removing the causative agent, sending for help, and informing the surgeon of the change in patient status. Maintain or gain access to a patent airway is imperative, along with administering 100% oxygen. Control of hypotension with epinephrine is the foundation in anaphylaxis management. Epinephrine’s mechanism of action is primarily alpha 1, providing vasoconstriction, and beta 2, providing bronchodilation. If bronchoconstriction is persistent, administration of a direct beta 2 agonist may be indicated. Salbutamol or albuterol are common beta 2 agonists used in anesthesia. Fluid management with sodium chloride 0.9% or colloid administration is recommended for the rapid fluid shifts that occur due to vasodilation and capillary leakage. Management of histamine blockers, both H1 and H2, and corticosteroids are used to treat angioedema and cutaneous symptoms (Mertes et al., 2010). IgE mediated anaphylaxis in the intraoperative setting is primarily caused by neuromuscular blocking agents, followed by latex and antibiotics (O’Donnell, 2014). Recognition and treatment is crucial for optimal patient outcomes. The anesthesia provider must remain vigilant in patient assessment in accordance with medications administered to the patient. This vigilance will empower the anesthetist to appropriately provide the correct treatment. INTRAOPERATIVE ANAPHYLAXIS 5 References Butterworth IV, J. F., Mackey, D. C., & Wasnick, J. D. (2013). Anesthetic Complications. In Morgan & Mikhail’s Clinical Anesthesiology (5th ed. (pp. 1199-1229). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. Ebo, D. G., Fisher, M. M., Hagendorens, M. M., Bridts, C. H., & Stevens, W. J. (2007). Anaphylaxis during anesthesia: diagnostic approach. Allergy, 62, 471-487. Jacobson, J., Lindekaer, A. L., Ostergaard, H. T., Nielsen, K., Ostergaard, D., Laub, M., ... Johannessen, N. (2001). Management of anaphylactic shock evaluated using a full-scale anesthesia simulator. ACTA Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica, 45, 315-319. Mertes, P. M., Tajima, K., Regnier-Kimmoun, M. A., Lambert, M., Iohom, G., GueantRodriguez, R. M., & Malinovsky, J. M. (2010, July). Perioperative Anaphylaxis. Medical Clinics of North America, 94(4). Norred, C. L. (2012). Anesthetic-Induced Anaphylaxis. AANA Journal, 80, 129-140. O’Donnell, M. P. (2014). The Immune System and Anesthesia. In J. J. Nagelhout, & K. L. Plaus (Eds.), Nurse Anesthesia (5th ed. (pp. 1015-1035). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.