4. Art NOW? - New Scholar

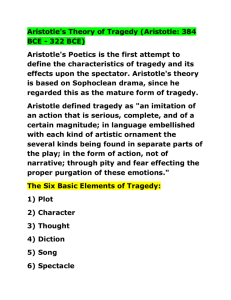

advertisement

TRAGEDY AT THE ROOT OF SCIENCE 1. some questions This paper attempts to cast some new light on the question of art’s relation to knowledge. The pedagogical (e.g. Brophy, 1998, pp. 201-243), epistemological (e.g. Carter 2005), and even economic (e.g. Haseman and Jaaniste, 2008, pp. 2326) significance of art’s contribution to knowledge has been much discussed over the last decade. One of the key sticking points, as far as higher degree research goes, has been the question of whether i) an artwork conveys knowledge in its own right, or ii) whether one needs an exegetical supplement to convey the knowledge the work betokens, which might include the knowledge that arose in the process of the work’s production (e.g. Vellar 2003; Fletcher and Mann, Eds. 2004).i I confess that I am not a fan of either of these positions: that there’s knowledge in the work for all to see; that there’s knowledge to be extracted from the work for all to see. What both positions foreclose is the possibility that work in the arts might be less concerned with the construction of knowledge than the framing of questions. I’m going to argue just this. The thing that modern art — the sort of art capitalist societies produceii — has to offer the research process is not a knowledge report, but rather an opportunity for the work’s reader or viewer to construct one. Art takes the form of a research question. I’ve said I want to shed new light on the question of art’s contribution to knowledge but actually the position I’ve just tabled is a very old one. What I really want to do is brush off an old lamp and light it. I’m referring to Aristotle’s Poetics (Aristotle 1995; 1997), a text which has received surprisingly little airing in this debate. We forget to our peril the similarity between Aristotle’s situation and our own. For Aristotle was labouring in the shadow of Plato’s extraordinarily powerful repudiation of art’s status as knowledge (e.g. Plato 1925). The answer Aristotle constructed in response to his master is embodied in the Poetics (Halliwell 1997, p.1). What’s striking about Aristotle’s answer is that it has nothing to do with treating an artwork as a knowledge report, whether explicitly, implicitly or otherwise, nor does it have anything to do with any ‘practice-led’ knowledge an artist might discover in the process of trying to communicate his or her ideas through the resistant material form of the work (pace Carter 2005, pp. 1-15). To the contrary, it’s all about how the work generates inquiry and investigation in others. It’s all about art’s status as research question, its tendency to confound its audience and thus instil in them a desire to make sense of just what has been so confounding. It creates scientists of us. In what follows, I’ll set forth something of Aristotle’s theory of the classical art of Greek tragedy, the art form which he believes most embodies the function of precipitating inquiry in others. I’ll show how Aristotle conceived of the matter in relation to the 4th century BC stage, and I’ll argue for the relevance of his views to the sort of art we ourselves produce in our function as contemporary artists / researchers. 1 But before I do any of that historical or theoretical work, I want to bring to your mind just what it is that we’re arguing over. I don’t want this to become, as we Australians say, a dry argument. To this end, I’m going to flick through the pages of ART NOW vol.2 (Grosenick 2008) and ART NOW vol.3 (Holzwarth, 2008), both of which were published by Taschen in 2008. Where possible I’ll include web links to these images, or to alternate versions of them. I’ll flick through a few other catalogues and websites that concern artists represented in these two volumes too. Forget about Aristotle for the moment, forget about inquiry and forget about knowledge. This is what people are producing right now:iii Blind Richard Attenborough (Black Eyes), Blind John Hurt (White Eyes), Blind Carol Lonely (White Eyes) and Blind Talullah Bankhead (Silver Eyes) comprise four works from Douglas Gordon’s 2004 series 100 Blind Stars. Each features a publicity still of a 40s or 50s Hollywood star, though the eyes have been excised and replaced with mirrored black or white paper (Grosenick, 2008, p.107). http://www.pedesign.co.uk/work/ngs/douglasgordon/highlights_4.html Jonathan Hernandez’ Estado Vacioso (2007) is a panel of 48 photos, cut from newspapers, of contemporary politicians, athletes, a conductor and various other iconographic figures. From each photo Hernandez has excised a perfect circle. This excision appears as a ball in the hands, hovering around the head, or spinning on the pointing finger of Perez Musharraf, Mahmoud Ahmadinajad, Tony Blair, a basketballer photographed from behind, an impassioned Colin Powell at the UN. The translation is ‘Vacant State’ (Holzwarth, 2008, p.234). http://www.taschen.com/lookinside/04431/index.htm [enter ‘234’ in the bottom menu] For the Love of God (2007), by Damien Hirst, is a platinum cast, with real human teeth, of a human skull covered with 8601 flawless diamonds (Holzwarth, 2008, p.249). http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x25f5k_damien-hirst-50m-diamondskull_news Santiago Sierra’s 10 inch Line Shaved on the Heads of Two Junkies who Received a Shot of Heroin as Payment (2000) is the photographic documentation of the transaction referred to in the work’s title. The junkies are photographed from behind, in tatty t-shirts, head to head so that the line will add up. http://www.santiago-sierra.com/200011_1024.php Marlene Dumas paints from Polaroids and newspaper photos. Her Chloriosis (Love Sick) is a 1994 work featuring 24 sheets of paper with ink, gouache and polymer paints. Each sheet presents a face, foreshortened to an awkward 2 closeness, so much so that you can’t work out if the subject is naked or clothed. The features range from anaemic to enraptured (Dumas, 2008, pp.100-101). http://www.moma.org/collection/browse_results.php?object_id=37856 Visitors entering the Guggenheim Museum of Modern Art, to visit Cai GuoQiang’s retrospective I Want to Believe in 2008, were met in the precipitous white foyer by an installation of nine new automobiles cascading in a chain from the ceiling. Sequenced multi-channel light tubes projected in all directions from each vehicle, pulsating on and off as if to register the impact. (Holzwarth, 2008, p.85). http://pastexhibitions.guggenheim.org/cai/cai.html A detail of an untitled installation by Robert Gober features the body of a gaunt Jesus, in crucifixion (2005). He has no head. The customary wound appears incised below his right breast. It is curiously free of blood. His loin cloth is neat and unrevealing. Where his nipples would be, Gober has installed two gushing streams of water, which fountain from Christ’s breasts and into the surrounding space (Grosenick, 2008, p.103). http://www.matthewmarks.com/index.php?n=1&a=141&i=841 [click on image for close-up] Couple was painted in oils over 2003-4 by Cecily Brown. At 228.4 x 203.2 cms, this massive canvas is at once an abstraction of a forest of greenery and silver trees, and a figuration of the couple within it. One appears naked, the other seems to be in red. Each embraces an indeterminacy (Grosenick, 2008, p.43). http://www.mfa.org/exhibitions/sub.asp?key=15&subkey=2591 Tim Noble and Sue Webster’s Puny Undernourished Kid & Girlfriend from Hell (2004) is a work in neon, in two parts, The puny undernourished kid looks like a cartoon version of Noble, with love and hate tattoos on the knuckles, up and down arrows on the arms, and the following slogans over the rest of his body: victim, so what?, sod off, stupid cunt, wanker, fuck up, nasty man, piss off. The girlfriend from hell has take my tits, cunt face, dick, G-B-H, fuck everything and angry bitch (Grosenick, 2008, p.220). http://www.saatchigallery.co.uk/artists/artpages/noble_webster_puny_undernourished_kid.htm http://www.saatchigallery.co.uk/artists/artpages/noble_webster_girlfriend_from_hell.htm Glen Brown’s Sex (2003) is an oil portrait of a man in ruff. The background is totally black. He looks like a Rembrandt, though his face has the elliptical 3 dissymmetry of an El Greco saint on the way up. His face is in varying tones of congealed blue (Grosenick, 2008, p.47). http://www.artnet.com/Galleries/Artwork_Detail.asp?G=&gid=414&which=&Vi ewArtistBy=&aid=3162&wid=423887347&source=artist&rta=http://www.artn et.com Deepak Chopra is 2 metres high and 8 metres long. A 2003 oil on canvas by Richard Phillips, the painting is based on the relaxation entrepreneur’s own advertising portraits, only here are seven of him, lined up head to head and caught on the angle, each an identical images of openness and success (Grosenick, 2008, p.252). http://www.artnet.com/artwork/423780359/140527/deepak-chopra.html From October 2003 to March 2004, the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern became the site of Olafur Eliasson’s The Weather Project. A spherical arrangement of mono-frequency lamps was installed just below the ceiling, which itself was covered in foil to mirror everything below. A haze machine and the impossibly yellow-red glow of the sphere above flooded the Hall like a ‘giant mock solarium’ (Grosenick, 2008, p.86). Documentation shows viewers become participants as they lie on their backs on the floor of the hall and appear reflected in the ceiling above. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-dFOphuPqMo 2. the plot of Oedipus Rex These are the sort of artworks contemporary capitalist societies produce. How could they possibly relate to Aristotle’s poetics? How, given that almost nothing of what I’ve just described or shown to you would have been imaginable when Aristotle was writing in the 4th century BC? Classical art simply wasn’t produced this way. Well, that’s not entirely true. I’m going to argue that Aristotle’s Poetics offers the most cogent theory we have for just what is going on in works like these, not to mention modern poetry, high-art cinema, theatre, dance and so on. Specifically, it has most to tell us about how such works implicate the emotions of their viewers to engender shock, wonder and — at length — knowledge. Such works do so by taking the form of a question, a question addressed to their respective audiences. What the artist learnt in the process of producing any one of them is comparatively irrelevant. Their most significant epistemological function is to induce those who encounter them to think. But more on that later. For the moment, let’s focus on the Poetics’ classical relevance. I’m going to recount the plot of a play you might have seen: Oedipus is the King of Thebes. A plague has befallen his city. He sends an emissary to the God Apollo to inquire what he must do. The message from Apollo’s temple at Delphi is imperative: there is ‘an unclean thing’ on Theban soil: the plague will not cease till a killer is removed from the land (Sophocles, 4 1947, p.34). The person who killed Oedipus’ predecessor, Laius, must be found out and banished. Teiresias is summoned and his advice sought. Teiresias simply wants to leave. ‘Ask me / no more. It is useless. I will tell you nothing.’ (p.35) Oedipus, who had warmly welcomed the blind man, becomes angry at these ‘insults to the state’ and peremptorily accuses Teiresias of having been involved in the murder. The prophet hurls the accusation back at Oedipus: ‘I say that the killer you are seeking is yourself’. The attacks and counter-attacks continue till Oedipus, catching something Teiresias has said, falteringly replies OEDIPUS: What’s that? My parents? Who then . . . gave me birth? TEIRESIAS: This day brings you your birth; and brings you death. (p.38) Oedipus casts the prophet out and now begins wildly accusing his brother-in-law of having bribed Teiresias to name him as the killer. The Chorus, and then Oedipus’ wife Jocasta intervene. Oedipus will unravel the plot, and learn what happened to Laius. Only — ‘my wife, what you have said troubles me’ — Jocasta’s tale of Laius’ murder at a crossroads, with four of his servants, begins to plant seeds in his mind (p.46). He starts to recall a similar incident from his past: obstructed by an old man and his entourage on the road to Thebes, and in a rage, Oedipus killed them all. The king begins to worry that the ban he has pronounced upon Laius’ killer might well apply to himself. At this point, a messenger arrives from Corinth, the land of Oedipus’ father Polybus and his mother Merope. Polybus is dead. The news instantly brings relief to Oedipus who has long laboured under the curse he received from Apollo’s oracle at Delphi: that he would kill his father and marry his mother. It was for this reason that Oedipus, while still a young man, fled Corinth, only to arrive at Thebes, win Jocasta in marriage and thus become king. Only the news is not totally comforting. His father may well be dead, Oedipus tells Jocasta, but while his mother Merope lives he is still not safe from the curse. The Corinthian messenger overhears Oedipus say this. Aristotle regards the exchange that follows as the properly tragic moment of the play: MESSENGER: Was that the fear that has banished you all this while? OEDIPUS: Yes. I was determined not to kill my father. MESSENGER: Then let me rid you of this other fear. I came to do you good. (p.53) 5 The messenger now tells Oedipus that he need not worry about returning to Corinth. His mother Merope is not his mother. Nor was Polybus his father. ‘You were given to him — by me’ (p.53). The messenger explains that he in turn was given Oedipus by a shepherd from Thebes, a former servant of King Laius’. OEDIPUS: Is he alive? And could I see him? MESSENGER: Your people here should know. The chorus reply that the shepherd is the same servant who has already been sent for, the sole survivor of Laius’ entourage when he was killed. Jocasta begins to beseech Oedipus to cease his inquiries. She leaves the stage and kills herself. Oedipus is about to learn that his mother instructed a shepherd to leave him to die on Mount Cithaeron. Oedipus blinds himself with the golden brooches which fastened Jocasta’s dress. On his return to the stage the chorus tell him that he should have killed himself too. 3. Aristotle Aristotle sees Sophocles’ Oedipus as one of the prime examples of ‘the pleasure peculiar to tragedy’ (1997, p.97). He cites it accordingly. The Oedipus shares with Euripides’ Iphigenia in Tauris in receiving more references in the Poetics than any other play. As such, it constitutes a privileged point of entry into the Poetics, Aristotle’s notoriously difficult, beguiling and fragmentary theorisation of the intellectual and emotional impacts of tragic drama. I’m going to address Aristotle’s general argument about art and knowledge by way of these specific references. I’ll attempt, in due course, to show the relevance of that general argument to our present debate, up to and including how we might theorise the epistemological properties of the contemporary works displayed above. The bulk of these10 references to the Oedipus occur over chapters 11 to 15, which concern tragic ‘plot-structure’ and the way reversal ( [peripeteia] in the Greek) and recognition are structured into it. The first reference is to the scene I’ve just recounted, the messenger scene at the end of the play: Peripeteia is a [sudden] change [over] of what is being done to the opposite in the way we have said, and — as we have [also just] said — according to likelihood and necessity; as for example in the Oedipus, the [messenger] who has come to cheer Oedipus and free him of his fear about his mother, by disclosing who he is [actually] does just the opposite. (1997, p. 87) 6 So Aristotle fleshes out a distinction he has just made between simple tragic plots, which feature a ‘change in fortune’ for the protagonist, and complex plots, like that of the Oedipus. Complex plots have two other factors, in addition to the ‘change in fortune’. The first is peripeteia or sudden reversal, where a character performs an action intended to do good, for example, only immediately to find it result in disaster, as here. The second feature is recognition, ‘a change from notknowing to knowing’ one’s tragic fate (p.87). We’ve just seen how Oedipus recognises his fate, following upon the reversal cited above. Aristotle’s second reference to the play draws attention to this: ‘the finest recognition is when it happens at the same time as the peripeteia as in the Oedipus’ (p.87). A third reference immediately follows, in which Aristotle adds that this very combination of reversal and recognition is what produces the customary emotions of pity and fear in an audience. Which is to say, this combination of reversal on the one hand, and recognition of one’s catastrophe on the other, is what engenders the ‘pleasure peculiar to tragedy.’ Tragic pleasure is not, Aristotle will proceed to tell us, just a response to indiscriminate suffering. Nor can it be elicited through masks and costumes, though they may serve to elicit an inferior sort of ‘shock’ (p.99). As for the sort of plot that splits its cast into ‘the good guys’ and the ‘bad guys’, and apportions appropriate fates to them, that’s more akin to comedy, and the distinct regime of pleasure it affords. None of the above concern what is essential: the tragic character’s structure of expectations, the way they are suddenly disrupted, and discovered to be wrong. It is all, in effect, about the subversion of the tragic hero’s knowledge. The easiest way to flesh out this thesis — that Aristotle believes tragic pleasure is about the subversion of the hero’s knowledge — is to ask, of scenes like the one singled out above, just what does the tragic hero recognise as he comes to grief? What does Oedipus recognise, as a result of the messenger’s ‘good news’? It is not merely a catastrophic fate. Specifically, it’s a catastrophic fate he did not expect. What the tragic hero comes to recognise is a catastrophe that his knowledge and awareness of the world did not equip him to grasp. It might have. That one might well have worked it out is essential: The best recognition of all is the one [that comes about] from the events themselves, when the shock of surprise arises from likely circumstances, as in Sophocles Oedipus Rex, and in the Iphigeneia – naturally she wanted to send the message. For recognitions of this kind are the only ones [that work] without invented signs and amulets. Second [to these] are the ones [drawn] from inference. (p.91) There are two things to note in this passage which comes from the list Aristotle gives in chapter 16 of the various types of recognitions tragedies can feature. Recognitions involving ‘invented signs and amulets’ would be, for instance, the sort of recognition that occurs on sighting another’s birthmark — which tells you who you’re sleeping with. Recognitions involving logical inference can be 7 witnessed every night on CSI, NCIS and virtually any other television detective show, where an investigator’s capacity to put two and two together serves the thoroughly comic end of separating criminal from law abiding normal people like the police. The main thing to note here, however, is Aristotle’s qualification of the idea that the hero’s fate should involve a sudden unexpected reversal, as seemingly good news turns to bad. This is true, but it’s not the sum total of what he’s saying. Not only should such reversals be unexpected. The catastrophes they betoken should be likely. That is to say, a tragic play needs to be plotted in such a fashion that the hero’s unravelling is entirely plausible. The messenger needs to have a real motivation for coming with this particular news at this time, and even more than that, it needs to be plausible for Oedipus to have killed his father and slept with his mother. The catastrophe cannot come from nowhere, it needs to be built into the very structure — albeit unbeknownst to him — of the hero’s world. I want to hone in on the relentless logic of the tragic universe for it really is integral to everything Aristotle is saying. It receives an even more precise formulation in chapter nine, where we read that tragedy concerns itself with events that are terrifying and pitiful, and […] events are especially [so] when they happen unexpectedly and [yet] out of [inner] logic — for that way they will be more wonderful than [if they happened] all by themselves or […] by chance. (p.85) ‘[O]ut of [inner] logic’: tragic catastrophe does not come from divine whim, nor is it a matter of chance as so many of our own personal catastrophes — i.e. car accidents — in fact are. To the contrary, it could have been expected. The issue is, I repeat, one of knowledge, or rather intellectual blind spots. It’s about the things one might well have known, but didn’t. In short, it’s about reality. It’s in this light that we have to understand Aristotle’s famous reference to the ‘tragic flaw’ in chapter 13. The ideal tragic hero, Aristotle writes, is the one who comes upon disaster not through wickedness or depravity but because of some mistake — [one] of those men of great reputation and prosperity like Oedipus. (p.95) This is George Whalley’s translation. Whalley offers ‘mistake’ as translation for the Greek αμαρτια [hamartia]: who comes upon disaster not through wickedness or depravity but because of some αμαρτια — [one] of those men of great reputation and prosperity like Oedipus. 8 Now αμαρτια was the word used by New Testament writers to render the Christian concept of sin, and it’s that usage of the word — a usage thoroughly foreign to Aristotle — which has coloured many modern receptions of this passage. So people talk of the tragic flaw as if it were a moral flaw, something close to sin, such as Macbeth’s ambition, or his malleability. Really, the word just means error, which is how Halliwell translates it (1995, p.71). Think of Oedipus: he’s paranoid and abusive, but that doesn’t alter the fact that he has no intention at all of killing his father, nor or sleeping with his mother. His failure is not a moral one. As he puts it, now blind and old, in Oedipus at Colonus, ‘The law/ acquits me, innocent, as ignorant, / of what I did’ (p.88). Aristotle’s word αμαρτια focuses us rather on a cognitive failure. Oedipus failed to realise what he was doing, even though there was an inner logic to it. He simply didn’t get it. The more you dig into Aristotle’s text, whether by way of these references to the Oedipus or otherwise, the more you come to realise that tragedy is overwhelmingly a question of knowledge. This knowledge takes a very particular form: tragic characters are ignorant of things they might well have known about their very own world. The reason they might well have known is that that world is a thoroughly logical one. Hence Aristotle’s repeated, even obsessive, references to the need for actions in tragedy — but not, mind, in epic or comedy — to occur ‘according to likelihood and necessity,’ a phrase which comes up again and again; it occurs 3 times in one sentence in chapter 15 (p.111). As Stephen Halliwell puts it, in his close study of the Poetics, ‘intelligibility must be preserved even at the heart of tragic instability’ (1998, p.104). Tragic heroes are not ignorant of the supernatural or the unlikely. Or rather, if they are, it doesn’t matter. The real danger lies in what they have failed to grasp about their own world, the things they might have made sense of, but didn’t. The catastrophe comes about ‘unexpectedly and [yet] out of [inner] logic.’ Tragedy aims directly at its hero’s ignorance, an ignorance he or she might well have remedied through science. 4. Art NOW? I’ve suggested that the Poetics will help cast light on the slew of contemporary artworks with which we began, and I’ve made that claim specifically in relation to their status for knowledge. I’ll turn to that shortly. But first, and as a way of bringing this text into the present, I want to say a little more about the two emotions Aristotle associates with the pleasure of watching Oedipus, and characters like him, come to grief: pity and fear. Recall our quote from chapter 9. Tragedy concerns itself with events that are: terrifying and pitiful […] events are especially [so] when they happen unexpectedly and [yet] out of [inner] logic — for that way they will be more wonderful than [if they happened] all by themselves or […] by chance This passage closely links the arousal of pity and terror in an audience to their observation of the hero undergoing what is essentially an experience of cognitive 9 dissonance, a clash between whatever was within his or her structure of expectations, and whatever exceeded them (and yet is undeniably real). But why do we respond in this way — pity and fear — to Oedipus’ horrible recognition of what he failed to realise? Why does it effect us when Creon, in the Antigone, learns that he has inadvertently caused his son and wife’s death, and could well have seen it coming too (1947, pp.155-161)? Why do we enjoy these symptomatic moments? One way to begin to answer is to unlock what Aristotle means by ‘pity and fear’. Now the Poetics doesn’t offer a theory of pity, nor of fear. It simply presents them as developed concepts. Aristotle’s Rhetoric, however, does offer such a theory. If we draw on this text we can start to reconstruct why pity might be a natural enough emotion to feel when witnessing tragic reversal and recognition. In chapter 8 of book 2 of that volume Aristotle articulates the following ‘general principle’: ‘what we fear for ourselves excites our pity when it happens to others’ (1952, p.633). We pity what we’re afraid of experiencing ourselves. We pity great men’s misfortune, for instance, because ‘their innocence … makes their misfortunes seem close to ourselves.’ (p.633) That is to say, we fear that a basically nice guy should suffer horribly, because we’re basically nice guys too and can imagine how it would feel if it happened to us. Likewise, we pity those experiencing ‘evil coming from a source from which good ought to have come’ (p.632), we pity reversals that is, because we can imagine ourselves on the receiving end of such thwarted blessings as well. Pity, for Aristotle, is really a form of self-regard — what if this were me? It has strong overtones of fear as well, which is doubtless what the conjunction ‘pity and fear’ is really getting at. What pity is not is an altruistic, or undifferentiated response to ‘sheer human vulnerability’ (Halliwell, 1998, p.174). Sheer human vulnerability only touches us if we can imagine ourselves suffering in a similar way. In short, these passages suggest that insofar as we feel pity and fear at Oedipus’ downfall, it’s because we can imagine ourselves the innocent and unrealising sufferers of all these things we didn’t know about our world too, though we might have. Ignorance as to who one was really sleeping with might be one example. Really it’s the theme of failed knowledge that gets us in, those moments where one simply does not recognise the trap one has entered and is now in. In Halliwell’s fine summary, ‘the emotional experience of tragic poetry does not take the spectator out of himself, but entails a deeper sense of the vulnerability of his own place in the world’ (1998, p.183). Insofar as it concerns the limits of knowledge, the Oedipus makes an Oedipus of all of us. What of Gober’s crucifix? I described it above as follows: A detail of an untitled installation by Robert Gober features the body of a gaunt Jesus, in crucifixion (2005). He has no head. The customary wound appears incised below his right breast. It is curiously free of blood. His loin cloth is neat and unrevealing. Where his nipples would be, Gober has installed two gushing streams of water, which fountain from Christ’s breasts and into the surrounding space (Grosenick, 2008, p.103). 10 http://www.matthewmarks.com/index.php?n=1&a=141&i=841 [click on image for close-up]) I’m trying to make sense of the visceral reaction I have whenever I encounter this work. It’s not disgust, that wouldn’t be true. There’s no real pity either, but I’d say an element of fear. I’m shifting, by the way, from the Oedipus to contemporary art, though I’m retaining Aristotle as my guide. For what these supplementary passages from the Rhetoric on the nature of pity tell us is that our pleasure in the Oedipus is all about being Oedipus — at least a far as ignorance and knowledge goes. It’s all to do with imagining ourselves totally vulnerable to what is unexpected and yet undeniably real. I’m suggesting that work like Gober’s puts us in precisely in that position too. There’s no room for pity of course, because we’re no longer talking about someone outside ourselves, that Oedipus over there. Pity can now take on its true form, which is fear, or at least an intimation of it. This was not expected and yet it’s real. In fact, the reality of Gober’s sculpture increases the more you think of it. What I mean is that when I start to think about this work what I realise is that I do find an inner logic to it. For my gut reaction might be to imagine that crucifixes have never appeared this way, but actually, that’s not quite true. The medieval historian Carolyn Walker-Bynum has traced a veritable tradition of 12, 13th and 14th century images of Christ — I’m referring to totally orthodox imagery here, works in churches and monasteries — which show him lactating, often so as to suckle others. She’s backed that archive up with letter from abbots, who describe their relation to junior monks as not just a nurturing but even a suckling one. They refer to themselves as ‘mother’, which incidentally reflects the title of Bynum’s collection of essays on the topic, Jesus as Mother, Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages (Walker-Bynum, 1984). As for the present, I am reminded by Gober’s sculpture of a conversation I had with the Australian prose-poet, Ania Walwicz. Ania’s father was a Polish army officer and she once told me that, growing up near the barracks, around that all-male environment, she frequently witnessed relationships of surprising tenderness and nurture between certain of the men. I recall this sort of maternal masculinity too from my days in an all-male secondary school — in fact I recall it even on the sports field. In Gober’s sculpture the tap’s up on full, of course, but that doesn’t stop it eliciting all these thoughts about an otherwise little-discussed aspect of the logic of gender within our cultures. It reminds you of maternal masculinity, however little you expected it. unexpectedly and [yet] out of [inner] logic In other words, when I look at this work it’s like the whole tragic theatre has been pared down, all the characters stripped away to the point where nothing remains but the audience member, their knowledge of the world and their encounter with a work that at once defeats that knowledge and yet demands to be recognised as real. This is the experience that Aristotle is getting at in the precise formula above and is one of the chief reasons I stated at the start of this lecture that Aristotle’s Poetics offers the most cogent theory we have for just 11 what is going on in works like these, not to mention modern poetry, high-art cinema, theatre, sculpture and so on. Let me table this as a massive historical thesis, that I submit can be tested on each one of the works presented above. Each in it’s own way defeats the viewers’ immediate approach: it is unexpected, and yet deeper acquaintance betrays an inner logic that might well have been recognised. That’s because these are tragic arts. Modern art has ‘the tragic pleasure’ at its core, and Aristotle is our prime theorist of it. That’s my thesis. Here’s some instances: http://www.nytimes.com/slideshow/2008/02/22/arts/22cai-slideshow_3.html It is unexpected that 9 actual cars suspended in a cascading chain from the ceiling should greet you as you enter New York’s Guggenheim Museum. And yet there is an inner logic here, which would be something like we see this sort of thing everyday on television and movies, or even: isn’t this what traumatic accidents feel like, those moments of infinite slowness and suspension, when all the world seems slowed to a single traumatic freeze frame? https://www.tate.org.uk/servlet/ViewWork?cgroupid=999999961&workid=81 203&searchid=14567&tabview=text It is unexpected that anyone will swap heroin for the chance to shave 10cms of hair off two junkies’ heads. Why would you sell your body in such an absurd way? And yet there is an inner logic here, which would concern the fact that we sell our bodies in absurd ways every day. Think of the part-time jobs our students do: is asking every customer would you like 3 mars bars for 2$ with every petrol purchase really that much more meaningful? Is it really less exploitative to engage people to perform such work? As for what we buy with the proceeds, how sure are we that we aren’t addicted to those purchases, to our own detriment: cigarettes, alcohol, house mortgages. Who are we calling junkies? http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/For_the_Love_of_God It is unexpected that we’ll die without taking at least some of this with us. I submit that what for Aristotle was the specific province of tragic poetry has now, in advanced capitalist societies, become the logic of high-art in general. It’s all about what defeats our knowledge and yet demands to be recognised as real. I’ll go even further: Aristotle’s formulation is measuring stick, by which you can measure up most any contemporary work you can name that aspires to being seen as real high-art, whether it be painting, installation, literature, theatre or even tattooing. Does it offer a scenario that is at once unexpected, and yet bears within it an inner logic, one we are compelled to recognise as real? There is an emotional component to this as well. As Aristotle tells us, if the work is merely unexpected, but has no other logic to it, it’s not likely to render us much pleasure. ‘[W]eak tragedy’ leads to rapid ‘satiety’ (p.131). On the other hand, you know you’re in the presence of something that is not merely unexpected but also 12 real when it continues to create that flutter of fear and wonder, long after the initial acquaintance with the work: http://www.pedesign.co.uk/work/ngs/douglasgordon/highlights_7.html These are tragic arts. This is where we are, blinded by them. 5. A Substantial Contribution to Knowledge terrifying and pitiful […] events are especially [so] when they happen unexpectedly and [yet] out of [inner] logic — for that way they will be more θαυμαστον [thaumaston] than [if they happened] all by themselves or […] by chance But why should this experience of our own incomprehension lead to knowledge, to a learning? On the other hand, why shouldn’t we hold that the artworks here surveyed do indeed bear knowledge within them, a very precise knowledge of just what is likely to do an audience’s heads in? We’re coming to the title of this paper, the tragedy at the root of science. Look at the phrase I’ve left in Greek above. Whalley translates θαυμαστον, thaumaston as ‘wonderful’ but adds a note to the effect that it means something more like ‘productive of wonder’ (1997, p.84-5). Aristotle is referring to the sort of plot that makes your head split with amazement as you try to imagine, in fear and pity, what it would be like to be in Oedipus’ situation at the moment he finds out. That Aristotle sees a scientific dimension to this is suggested by the gloss he makes on wonder in the Rhetoric: ‘wondering implies the desire of learning’ (1952, p.614). The plot-structure that is ‘productive of wonder’ will also be productive of learning. There is a simple reason for this: ‘the object of wonder is an object of desire’ (1952, p.614). Aristotle argument is that the tragic plot taps into the pleasure we feel in making sense. For ‘learning’, as he puts it in the Poetics, ‘is a very great pleasure, not just to philosophers, but in exactly the same way to any ordinary person.’ (1997, p.57). The tragic plot holds the pleasure of making sense out as a goal to us, precisely by luring us into a world in which our conceptual powers fail us. It inspires a research project in us. That is Aristotle’s riposte to Plato. It’s also, mutatits mutandis, Charles Saunders Peirce’s theory of ‘the circumstances which render an explanation of a phenomenon desirable or urgent’ (Peirce, 1992, p.91). Commenting that philosophers of science almost never stop to define this crucial component of scientific method — just what is it that calls for investigation? — Peirce adds that the ‘majority of them seem tacitly to accept that any one fact calls for explanations as much as any other’ (p.91). His analysis, on the other hand, makes clear that what lies at the root of science is the experience of what was unpredicted, and yet undeniably real: 13 In order to define the circumstances under which a scientific explanation is really needed, the best way is to ask in what way explanation subserves the purpose of science. We shall then see what the evil situation is which it remedies, or what the need is which it may be expected to supply. Now what an explanation of a phenomenon does is to supply a proposition which, if it had been known to be true before the phenomenon presented itself, would have rendered that phenomenon predictable, if not with certainty, at least as something very likely to occur. It thus renders that phenomenon rational, that is, makes it a logical consequence, necessary or probable. (p.89) In this statement we can already see how many worlds apart so much of science lies from the sort of art scientific societies produce. Or rather, we can see that contemporary art is a model of one pole of scientific process, the ‘evil’ one. For what modern artwork might be said to render phenomena predictable? On the other hand, a work that presents phenomena that comes at their audience ‘unexpectedly and [yet] out of [inner] logic’ clearly opens up the grounds for just such rationalisation. That is to say, it constitutes a research question. But this is already to suggest that we need to orient the much vaunted, and never adequately articulated, relation between art and science around a very particular moment in the scientific process: the originating one. Aristotle directs us there through his discussion of the pleasure in learning, Peirce through his discussion of science’s desire to resolve the unpredictable. In either instance, that which comes to us ‘unexpectedly and [yet] out of [inner] logic’ is the motor of inquiry. Peirce’s further comment that scientists have always had difficulty naming this is intriguing, and suggests a precise point of collaboration for scientists and university-based artist/researchers to explore in the future. They should both explore their indebtedness to tragedy — or rather, to give it is fuller name, trauma. I want to conclude by suggesting that such rejoinders to Platoiv constitute the grounds for a revivified theory and practice of creative research, whether at higher degree level or beyond. We should stop claiming — in opposition to the in-many-ways undeniable truth-claims of Cartesian science — that artwork in and of itself, and in contrast, provides privileged access to the truth of being (pace Heidegger, 2001). We should also abandon the ‘practice-led’ project of treating the scaffolding (research notes, odd theories, attempts and re-attempts) artists construct and then kick away to make their artwork as if it were more intellectually significant than the work itself. We need to start arguing that art’s intellectual significance lies in the learning process it seduces others into, by dint of its capacity to frame points of ignorance, in such a way that those points resound with a question: what was it about this that escaped my ken, and yet demands I acknowledge its reality? How can I make sense of this? Here is how I propose such works be assessed and judged for their contribution to knowledge. Of the next Doctorate in Creative Arts, or the next competitive 14 funding application in the Creative Arts — e.g. the next Australian Research Council (ARC) application for government funding of a work of art posed as research — the evaluative question should be: Does this work offer a scenario that is at once unexpected, and yet bears within it an inner logic, one we are compelled to recognise as real? In other words, is it likely to set off a research process in others? If so, it should be graded highly. An even finer way to delineate between the contribution such works have to offer knowledge would be to ask: In addition to the above, does it generate fear and pity? These should be the criteria the ARC adopt. This is the way we will get them to fund not simply, and peripherally, research about the production of art, but the actual art itself. 15 Bibliography Aristotle, Rhetoric in Aristotle II, trans. W. Rhys Roberts (Brittanica Great Books, 1952), pp. 593-679. —, The Poetics, in Aristotle XXIII, trans. Stephen Halliwell (Loeb Classical Library: Cambridge (Mass.), 1995), pp. 1-142. — , The Poetics, trans. by George Whalley (Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1997). Brophy, Kevin, Creativity: Psychoanalysis, Surrealism and Creative Writing (Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1998). Carter, Paul, Material Thinking: the Theory and Practice of Creative Research (Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing, 2005). Dumas, Marlene, Measuring Your Own Grave, catalogue (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 2008). Fletcher, J. and Mann, A. (Eds), TEXT: The Journal of Writing and Writing Courses, Special Issue on Illuminating the Exegesis, Website Series Number 3 April 2004, http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue3/content.htm Grosenick, Uta (Ed.), Art Now, Vol.2 (Cologne: Taschen, 2008). Stephen Halliwell, Aristotle’s Poetics, With a New Introduction (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). Haseman, Brad and Jaaniste, Luke, The Arts and Australia’s National Innovation System 1994-2008, Chass Occasional Papers No.7 (Canberra: Council for the Humanities and Social Sciences, 2008). Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought (New York: Harper Perennial, 2001). Holzwarth, Hans Werner (Ed.), Art Now, Vol.3 (Cologne: Taschen, 2008). See the on-line leaf-through version at http://www.taschen.com/lookinside/04431/index.htm Magee, Paul, ‘Is Poetry Research,’ in Text, The Journal of Writing and Writing Courses 13:2 (October 2009). Peirce, Charles Saunders, Reasoning and the Logic of Things, The Cambridge Conferences Lectures of 1898, Ed. K. L. Ketner (Harvard University Press, Cambridge (Mass), 1992). Plato, Ion, in Plato VII, trans. W.R.M. Lamb (Loeb Classical Library: Cambridge (Mass.), 1925). 16 Sophocles, Antigone, in The Theban Plays, trans. E.F. Watling (London: Penguin, 1947), pp. 126-167. —, Oedipus Rex in The Theban Plays, pp.25-69. Vellar, Richard, ‘Words and Music’, unpublished paper, CIRAC Colloquium on Creative Practice as Research, QUT, 19th September 2003. Walker-Bynum, Caroline, Jesus as Mother, Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984). Wu, Chin-Tao, ‘Biennials without borders?’ in New Left Review 57 May-June 2009, pp. 109-15. See also the list, which is appended to Fletcher and Mann’s special issue, of earlier contributions to the debate in Text: http://www.textjournal.com.au/speciss/issue3/exegesis.htm ii A brief discussion of this periodisation appears in this text at section 4. For further comment on the need for any discussion of art’s epistemological properties to distinguish the sort of artworks produced in capitalist societies from those of other social orders, see further the essay at footnote 3 of Magee 2009. iii This claim needs to be nuanced. The USA- and Euro-centricity of these two Taschen volumes is marked. For a critique of related problems at the Kassel Documenta and the Venice Biennale, see Chin-Tao Wu, ‘Biennials without borders?’ in New Left Review 57 May-June 2009, pp. 109-15. iv Peirce’s preference for Aristotle over Plato, which he poses as a preference for impartial method over ethics, is elaborated in chapter 2 of Reasoning and the Logic of Things (1998), pp.105-22. i 17