Scholarly Papers

advertisement

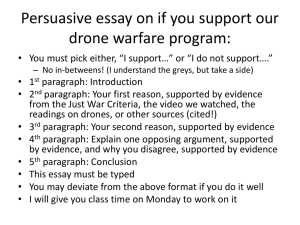

Guidelines for Writing Scholarly Papers Writing, even just a brief essay, is one of the most difficult tasks that you will face in college. It comes more naturally to some than to others, but it is almost never easy. And like everything else, writing clearly and effectively requires practice. This handout seeks to address the basics of writing, but there is no substitute for actually sitting down and putting your thoughts on paper in logical and coherent form. Scholarly writing has its own set of rules and conventions that are different from those of creative or technical writing. Formal academic writing is expected to conform to these standards, the most important of which are outlined below. Basic Structure: The introductory paragraph should engage the reader’s interest by setting out clearly the question that the paper is attempting to address, how you plan to address it, and why it is worth addressing in the first place. Often it is wise to begin with a brief story or anecdote, or a particularly powerful statistic, or an appropriate quotation. The key here is to make the reader want to keep reading. The thesis statement is a summation of your main point; this should generally appear at the end of the introductory paragraph. Before writing, try phrasing your thesis as a simple assertion (“The planet is running out of manganese”), and then develop it as you write by being as specific (and, indeed, as provocative) as you can: “Thanks to over-mining by American corporations, there is a very real possibility that the next generation will be forced to live in a world without manganese.” You should then provide background information, basic material about the subject, to provide context for the reader. Continuing the above example, you would want to say something about what manganese is and what it is used for. Depending on the amount of background you think is necessary, you might want to include this in the introductory paragraph; for longer essays a separate paragraph (or more) may be required. The real “meat” of your paper will be the actual points of discussion. These will be a series of paragraphs that support your thesis statement, with each point occupying one or two paragraphs, depending on the essay’s overall length. In this case, one might showcase statistics on how much manganese there is left in the world; another could contain statistics on how quickly the manganese supply is being depleted. The actual number of points, of course, depends on how much you have to say. One of the hallmarks of good writing is the ability to move back and forth smoothly between general statements and concrete details. Each paragraph should start with a generalization— sort of a miniature thesis statement. The rest of the paragraph should provide specifics to back it up; these might include reasons (Corporations have been over-mining manganese because….), examples (The supply of manganese in Zaire is at an all-time low….), expert testimony (Joe Baggadonuts, considered by some the father of the modern manganese conservation movement, says….), or statistics (In the past twenty-five years more than 20 million tons of manganese have been taken from the earth.). Always remember, however, that every sentence in any given paragraph should be devoted to making one individual point, and nothing else. “Manganese is a mineral element that is both nutritionally essential and potentially toxic. The derivation of its name from the Greek word for magic remains appropriate, because scientists are still working to understand the diverse effects of manganese deficiency and manganese toxicity in living organisms.” The concluding paragraph should flow logically from the rest of the essay, but it should be more than simply a restatement of what you have done. For a paper of more than three or four pages, you might want briefly to summarize your main points. The concluding paragraph might also offer some guidance for action (The time has come to stop the rampant depletion of the manganese supply….). In general, the same sorts of strategies employed in writing an introductory paragraph—using an anecdote, a quote, or a telling statistic—apply to conclusions as well. However, although your conclusion should refer back to your thesis statement, if should not merely be a rewording of what you said in the introduction. Ideally, your conclusion should convince the reader that he has not been wasting his time, and that there is something that he can take away from your essay. Things to Avoid: Contractions: Words like “didn’t,” “couldn’t,” and “wouldn’t” should not appear in scholarly writing. Instead use the full words. Apostrophes should only be used to indicate possession (for example, George Washington’s presidency). Passive Voice: “Washington chopped down the cherry tree” sounds a lot better than “The cherry tree was chopped down by George Washington.” The former is simple and straightforward; the latter is wordy and clumsy. Occasionally you will have no choice but to use passive—for instance, when the subject of the sentence is unknown—but in most cases you should use the active voice. First or Second Person: In scholarly writing, the author is assumed to have “distance” from his or her subject. You should therefore write as an outside observer, not a participant, and you should treat the reader in the same way. This means that pronouns such as “I,” “we,” or “you” are inappropriate. Note that this document is not an example of good scholarly writing (it is, rather, a piece of technical writing). Incomplete Sentences: Every sentence must have a subject and a verb, unless it is part of a direct quote. There are no other exceptions to this rule. Imprecise Language: Use words that express your point exactly. If you write, “Theodore Roosevelt was a good president,” the reader will probably be left wondering what you mean by that. You might have meant that he was an effective president, or a strong president, or a morally upright president. Therefore the words “effective,” “strong,” or “morally upright” are all far preferable to “good.” Slang: In conversational English it is perfectly acceptable to use phrases such as “bumped off” to describe a killing, or “laid back” to describe someone with a relaxed attitude toward life. However, such language has no place in scholarly writing (unless it is part of a direct quote). In general, try to imagine how a reader one hundred years from now would react to your words. What would your reaction be to a paper that referred to something as the “bee’s knees” (an expression that was in vogue one hundred years ago)? Words Out of Proper Proximity: We see sentences like this all the time, and they are frequently good for a laugh. For example, “Witnesses described the thief as a six-foot-tall man with a mustache weighing 190 pounds.” What weighed 190 pounds? This sentence would lead one to believe it was the mustache, when clearly the author meant the thief. Excessive Wordiness: Do not use more words than you absolutely need to in order to make your point. For instance, do not write “time period,” when either “time” or “period” will suffice. Do not write “due to the fact that,” when a simple “because” will do. Students do not get extra credit for using extra words. “Some students view the paper assignment as a chance to free-associate. They consider the question or task assigned by the professor as more of a suggestion (or "prompt") of something to talk about, rather than a focused request for discussion of a specific issue. Professors, especially ones who have spent hours writing up the assignment, don't view this kindly. In our experience, students lose more points from not answering the question than for making errors in what they write.” Excessive Quotation: Often writers who have yet to develop their own “voice” have a tendency to use a lot of direct quotes from other authors. This is tedious for the reader, and likely to leave him wondering whether you have anything original to say. Wherever possible, paraphrase the work of other authors instead of quoting them directly. Limit quotes to instances where the author uses a particularly striking turn of phrase, and where his or her precise meaning would be lost in a paraphrase. Dumb Mistakes: College students ought to know better than to confuse “its” with “it’s,” “there” with “they’re” or “their,” and “who’s” with “whose.” At the college level students should know that subjects must agree in number with verbs, and pronouns with their antecedents; for example, “Each of them had their own ideas” is wrong. “Each of them had his [or her] own ideas” is correct. Errors like this will cause the reader to question the basic intellectual capacity of the author. Plagiarism: Most are familiar with the notion that it is wrong to pass of another author’s work as one’s own. However, there are more ways of doing this than simply by copying another author’s words (or cutting and pasting from the Web). Some seem to think that by changing a few words one can avoid an accusation of plagiarism. This is wrong; avoiding plagiarism means citing every single source that you used in writing a paper—and “use” means draw any sort of fact (except those which are common knowledge) or interpretation. Plagiarism is the worst form of professional misconduct that there is in the discipline of history, and I will punish it to the fullest extent. Things to Do: Use Proper Style for Notes and Bibliographies: If a particular writing assignment requires the use of footnotes or endnotes, make sure they, as well as your bibliography, conform to the proper style. In the discipline of history that means Chicago style (sometimes referred to as “Turabian”). Your best bet is to obtain a copy of Kate L. Turabian, et al., A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses, and Dissertations (9th revised edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), and follow its standards rigorously. Pay Attention to Tense: By definition, historical events are things which happened in the past; therefore it only makes good sense to use the past tense when discussing them. The only exception to this rule comes when you are referring to a primary source of some kind, such as an important document, a book, or a piece of art. For example, you would write, “The Declaration of Independence states that ‘all men are created equal.’” Staple: Using paperclips, or folding back the pages on one corner, isn’t enough. I will not accept papers that are not stapled together. Use Page Numbers: This way, if your pages do become separated, I’ll easily be able to reassemble your paper. Proofread: If there is one rule that every writer (scholarly or otherwise) will agree on, it is that the first draft is never the last. Go back over what you have written again and again, until you are completely satisfied with the result. Ask yourself some hard questions: Is my introductory paragraph sufficiently enticing to the reader? Are all of my statements (and particularly my thesis statement) clear and easily understood? Have I given the reader enough background to understand my argument? Do all of my points of discussion back up what I said in the thesis statement? Does my concluding paragraph follow logically from the rest of the essay? Also, be sure to check spelling, grammar, and usage. Spell-check is a handy feature, but it will only get you so far. Matters like subject-verb agreement and word choice may sound petty, but they are vitally important. Sloppiness in this regard will suggest to your reader—even if it is only your instructor—that you have not taken your subject seriously. And if that is the case, why bother to read your work at all? If your scholarly work flows true with the guidelines provided here, you will, no doubt, be a successful academic writer in all your educational pursuits.