Two Births, Two Nations The Old Testament lectionary reading for

advertisement

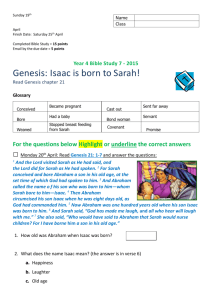

Two Births, Two Nations The Old Testament lectionary reading for this morning comes from Gen. 21. We don’t often have opportunity to spend some time in Genesis, so that is what I’d like to do a bit this summer. Though we join Genesis here almost in the middle of the book, this is where the lectionary picks up after initiating the reading of Gen 1 and a portion of Gen 2 last week. What makes this reading for today particularly interesting is that speaks to the two major holidays we are now in between. It has to do with family turmoil and provides something of a “reality check” after the focus on God as the ideal of fathers last Sunday. The reality is, no earthly father fully measures up to God’s standards, since we are all sinners. Notwithstanding, God can and does work out his purpose despite the frailties of the human condition. It also has a national focus, also something of a different check as we approach Independence Day on July 4. And it certainly has to do with the perennial issue of Mideast conflict and possibilities of peace. The chapter begins with the fulfilment of God’s promise to Abraham of an heir. You’ll remember that God had called Abram out of the polytheism of the land of Chaldeans to go to Canaan. God had said to Abram, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed (Gen. 12:1-3). Abram was 75 years old when he departed from Haran with his wife Sarai for Canaan (12:4-5). Along the way Abram becomes concerned when the promise of God will be realized. He asks God whether it will be realized through his servant Eliezer, since God has given him no children. God stipulates that a son coming from his own body will be his heir. God shows him the stars and says that’s how many his offspring will be. Gen. 15:6 then says of Abram, “he believed the Lord; and the Lord 1 reckoned it to him as righteousness,” words the apostle Paul cites in the NT for the doctrine of justification by faith. Abram believed God, but he didn’t understand what God was doing! Abram, Sarai, and their servants would be living in Canaan for ten years before the next major event, when Sarai tells Abram that since God has kept her from having children, he should sleep with her maidservant Hagar: “it may be that I shall obtain children by her.” So, Abram does as Sarai urged, and Hagar the slave-girl conceives a child to be named Ishmael, which means God hears. “He shall live at odds with all his kin” (16:12). Abram is 86 when Hagar bears this son and names him Ishmael. Thirteen years pass and God appears to Abram again, reminding him of the covenant and his promise and giving him the sign of circumcision for all the males of his house. God explicitly says he will give Abram a son through Sarah (17:16), to which Abram laughs. “Abraham fell on his face and laughed, and said to himself, ‘Can a child be born to a man who is a hundred years old? Can Sarah, who is ninety years old, bear a child?’” (17:17). It wouldn’t seem possible, but God assures Abraham it is so: “Your wife Sarah shall bear you a son, and you shall name him Isaac” (17:19), which means “he laughs.” “I will establish my covenant with him as an everlasting covenant for his offspring after him” (17:19). Ishmael will also be blessed and become great, the father of “a great nation” (17:20), but the covenant promise to Abraham is fulfilled in Isaac. It is in Gen. 21 that this all comes to a head! Sarah conceives and bears Abraham their promised heir, the son named Isaac, whom Abraham circumcises in obedience at eight days. Two or three years later perhaps, when Isaac is weaned, Abraham throws a feast, but Sarah “saw the son of Hagar the Egyptian, whom she had borne to Abraham, playing with her son Isaac” (21:10). The nature of the play can only be conjectured, but some suggest there was something sexual about it, since the Hebrew word is sometimes used that way. Others think it best simply to say that the word, which is the verb from which the name Isaac comes, 2 means that Ishmael was acting like he was the one for whom the party was held; he was “Isaacing,” so to speak, setting himself up as an equal to Isaac though only the son of a slave girl. Talk about family turmoil! Abraham is a model of faith, but he had some serious family issues! It was partly because he’d listened to his wife that he was in this pickle , but mostly because of doubting God! Now Sarah demands that Abraham cast out the slave woman with her son! Sarah is now the one contemptuous of “the other woman” she’d in fact invited into intimacy with her husband. Abraham is very disturbed about this, primarily because he has a genuine love for Ishmael. In addition, it may have been against custom to send him away, since ancient Near Eastern law held the son of a slave woman to have a claim on his father’s property. Abraham wants to do the right thing and it is up to him to issue the decision. God tells Abraham, however, “whatever Sarah says to you, do as she tells you, for it is through Isaac that offspring shall be named for you” (21:12). God can and does use the foibles of human beings to accomplish his purposes. “Here is an instance of God using the wrath of a human being to accomplish his purposes. A family squabble becomes the occasion by which the sovereign purposes and programs of God are forwarded” (Victor Hamilton). Sometimes it is hard to understand how God can be accomplishing his purposes through the frailties and foibles of sinful humanity. In another context, Rev. 17:17 says “God has put it into their hearts to carry out his purpose,” and so he does. There is some reason for why things occur. It is not all arbitrary and random, though to us it often seems that way. God remains in charge, carrying out his will, through all the idiosyncrasies and even evil of humanity. In the end, God’s will is done on earth as it is in heaven. Abraham and Sarah should have believed God more fully than they did, instead of taking matters into their own hands, but we can all certainly sympathize with their plight. Who of us would have done any differently? They remain remarkable paragons of faith, even despite their failings. That also should encourage us! We can be the same, faithful friends of God, despite our failings. 3 Abraham reluctantly sends Hagar and Ishmael on their way the next morning with some bread and water for a difficult journey in the wilderness of Beersheba. I can say from my brief time in the Holy Land that those wilderness areas would be difficult to survive in, with the tremendous heat, animals of prey, and little water. But God has also promised to make of Ishmael “a nation,” though he is not the one by whom the promise will come. Who are these nations? Well, the Jews are, of course, the children of Abraham through Isaac, while the Arabs and Muslims think of themselves as the children and progeny of Ishmael, according to Muhammad’s claim. In fact, we will see next week that the Qur’an replaces Isaac as the child Abraham is called to sacrifice with Ishmael. Indeed, the Qur’an conflicts with the Torah in just about every point as regards Abraham. And so it should not surprise us that Arabs and Jews have been in conflict from the outset, as we see yet today. Still, there is a deeper idea of nationhood involved here, a spiritual one. As Paul says, “not all Israelites truly belong to Israel, and not all of Abraham’s children are his true descendants; but ‘It is through Isaac that descendants shall be named for you’. This means that it is not the children of the flesh who are the children of God, but the children of the promise are counted as descendants” (Rom. 9:6-8). What Paul is saying is that it is not physical birth through the line of Abraham that counts one as a child of Abraham and heir of the promise, but spiritual birth in him who is the fulfillment of the promise: “If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to the promise” (Gal. 3:29). It is believers in Christ who are the true children of Abraham, “a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people” (1 Pet. 2:9). As much as we love America and wish the best for her, “our citizenship is in heaven” (Phil. 3:20) first and foremost. As much as we pray for and work for God’s blessing on America, let us recognize that we have a greater citizenship with all who belong to Christ throughout the world. We belong to that great nation whom no one can number, as many as the stars of heaven, who are blessed in father Abraham, the one by whom God achieved his promise of redemption in Jesus Christ. 4