Notes bio rev

advertisement

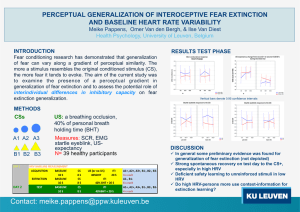

Problems: Participants selected shocks that were highly annoying but not painful. Maybe PTSD participants selected different shocks Is one day sufficient extinction recall interval? – not very helpful for improving treatment as time in between effects successful extinction – maybe PTSD just difference in time taken to overcome barriers of spontaneous recovery PTSD clinical classification system? (search) PTSD not all the same (extreme and lesser extents) There are two main theoretical perspectives on extinction. One is that the link from CS representation to US representation weakens over repeated extinction trials (e.g. Rescorla-Wagner predicts this). The other is that extinction trials create a new inhibitory association between CS and US representations that counteracts the excitatory one. Good points: The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) has proven to be a valid and reliable indicator of PTSD (Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). Neurobiological Basis of Failure to Recall Extinction Memory in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A review of the 2009 Milad et al. Study Extinguishing the fear responses associated with PTSD is of high importance in a clinical setting and so a better understanding of the neural correlates may help us to develop more efficient treatment programmes. A common way of studying fear responses, is by using a Pavlovian conditioning paradigm. This is where an unconditioned stimulus (US) which is innately aversive to the individual (e.g. an electric shock), is paired with an innocuous stimulus (e.g. a tone). After repeated instances of this pairing, presentation of the CS alone becomes sufficient for eliciting a negative response in the individual (CR). In relation to PTSD, the traumatic event (US) has a negative impact on the individual (UR). This leads to all stimuli associated with the event becoming conditioned to elicit a fear response (CR), despite the absence of any aversive effects themselves. However extinction would predict that the fear CR would disappear over time due to the lack of any negative consequence of the associated stimuli. Extinction of a fear response is the process in which the CS is presented without any negative consequence and thus gradually results in a decrease of the CR. In experiments such as that of Milad et al., the initial training of this dissociation is referred to as extinction learning, whereas the test for consolidation after a period of time is extinction recall. These are distinguished between as it is thought that they involve separate neural mechanisms. Specifically the amygdala is thought to be involved in the process of extinction learning. Conversely for recall, the hippocampus, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) have been implicated. WHERE Milad and colleagues investigated the neural correlates of impaired extinction in sufferers of PTSD by employing a two-day fear conditioning and extinction programme. They compared sixteen participants who currently suffered from PTSD, to fifteen who were trauma-exposed but who had not developed PTSD. One the first day, participants were habituated with images of three different colours of a lamp light depicted in two room contexts. They were then subjected to conditioning in one of the contexts, whereby two of the colours (blue and red; CS+) were followed by a shock 60% of the time (US). There were 8 trials for each, and 16 of the third colour (yellow) which was always innocuous (CS-). After about a minute the extinction training began where one of the CS+, the blue light, was shown during 16 trials within the other room context and without a shock. The CS- was also presented 16 times, without a shock as before. Finally on day 2, extinction recall was observed by presenting 8 blue, 8 red, and 16 yellow lights all within the extinction learning context and in the absence of any shocks. The experimenters measured participants’ skin conductance response (SCR) as well as blood-oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) data through a fMRI machine. They found that as predicted, there were no significant differences between the SCR data for the PTSD and TENC groups during extinction training on day 1. However on the second day, PTSD subjects demonstrated impaired extinction recall. fMRI data revealed greater activation in the amygdala of PTSD individuals during extinction learning, while for extinction recall, greater activation was evident in the dACC and lesser in the vmPFC and hippocampus. The researchers conclude by reiterating that the mechanism for extinguishing fear is compromised in sufferers of PTSD. One thing the researchers fail to acknowledge is that the type of trauma experienced by participants in their PTSD group was not matched with that of the TENC group. In their table of demographics (Table 1, p. 1076), the PTSD group are described as having 8 cases of sexual assault and 6 of childhood abuse. This compares with 2 sexual assaults and 1 childhood abuse in the TENC group. However research has suggested that type of trauma may be a fundamental risk factor for the onset of PTSD (Nemeroff et al., 2006). Specifically, these. Because the researchers do not provide individual demographic information about each participant it is difficult to determine the actual percentage of each group who were exposed to at least one of these trauma types. Also the mean age for the PTSD group was 17, while for the TENC group it was 22. Indeed they used a statistical test to determine this difference as negligible, but some developmental psychologists would argue that significant maturation may take place in these few years (Arnett, 2000). In fact, in his model Levinson (1977) proposed 17 to 22 years of age as a stage of early adult transition where we leave adolescence and begin to make choices for adult life. Understanding what mediates the development of posttraumatic stress disorder would help in the future development of effective treatment strategies. Also taking a pavlovian conditioning approach to PTSD is rather reductionist - the memory of a traumatic experience and the impact it has on an individual is more complex than what is possible to explain using US/CS associations. Firstly, PTSD can result from just one incident, whereas pavlovian conditioning emphasises repeated US/CS pairings leading to the learned association. The extinction process will not erase the complex fear memory, even if the basic CS/CR link is treated. And so due to such a detailed memory of the event and the feelings felt at the time, fear reponses will often reoccur (Quirk & Milad, 2010).Flashbacks and even nightmares may be just as effective at reinforcing the fear associations. So therefore the results of Milad et al.'s study may not have as much clinical application potential as one might have hoped. Instead studies have begun to explore ways in which to tackle the stored memory. It is found that when fear memories are recalled, they go through a reconsolidation process. Therefore directly disrupting this critical period may be more useful than simply extinguishing fear responses through repeated exposure to safe CS's. Researchers are now exploring drugs that do just this, for example Kindt, Soeter and Vervliet (2009) found that administering propranolol before reactivating a feared event memory led to a cessession in startle potentiated reponses upon exposure a day later. Preliminary studies with selective brain steroidogenic stimulants (SBSSs) suggest a new route to explore for treating PTSD, based on the finding that levels of allopregnanolone is decreased in sufferers, which SBSS's can counter (Pinna & Rasmusson, 2012). It has been shown that extinction may be more or less effective depending on the interval of time between the