Handout

advertisement

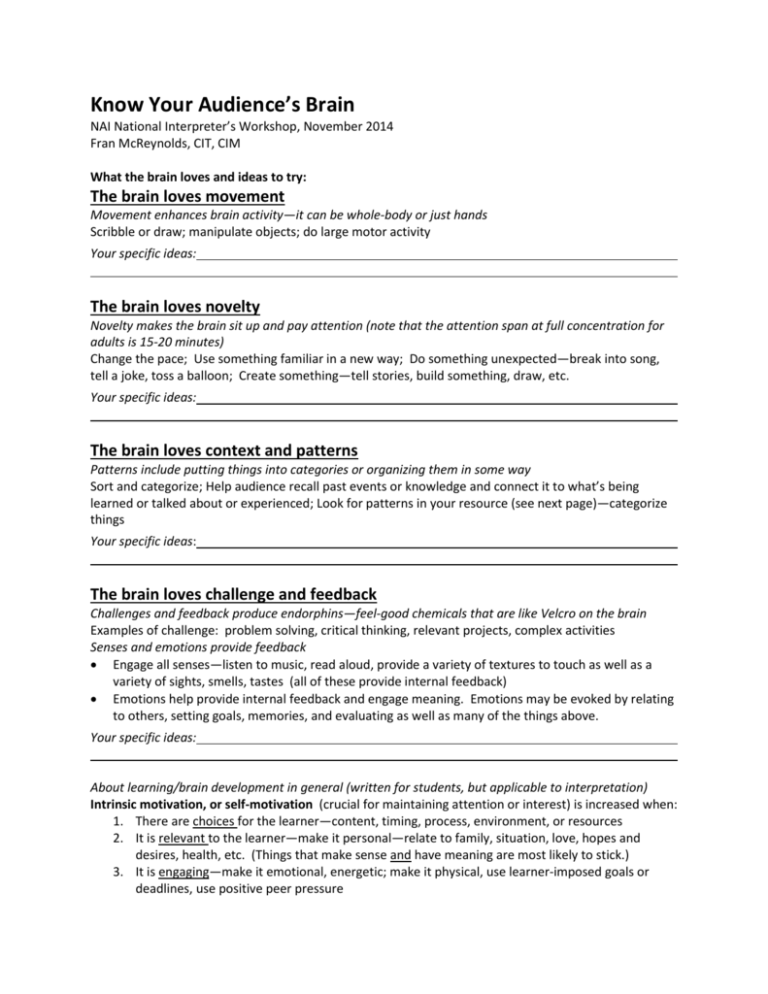

Know Your Audience’s Brain NAI National Interpreter’s Workshop, November 2014 Fran McReynolds, CIT, CIM What the brain loves and ideas to try: The brain loves movement Movement enhances brain activity—it can be whole-body or just hands Scribble or draw; manipulate objects; do large motor activity Your specific ideas: The brain loves novelty Novelty makes the brain sit up and pay attention (note that the attention span at full concentration for adults is 15-20 minutes) Change the pace; Use something familiar in a new way; Do something unexpected—break into song, tell a joke, toss a balloon; Create something—tell stories, build something, draw, etc. Your specific ideas: The brain loves context and patterns Patterns include putting things into categories or organizing them in some way Sort and categorize; Help audience recall past events or knowledge and connect it to what’s being learned or talked about or experienced; Look for patterns in your resource (see next page)—categorize things Your specific ideas: The brain loves challenge and feedback Challenges and feedback produce endorphins—feel-good chemicals that are like Velcro on the brain Examples of challenge: problem solving, critical thinking, relevant projects, complex activities Senses and emotions provide feedback Engage all senses—listen to music, read aloud, provide a variety of textures to touch as well as a variety of sights, smells, tastes (all of these provide internal feedback) Emotions help provide internal feedback and engage meaning. Emotions may be evoked by relating to others, setting goals, memories, and evaluating as well as many of the things above. Your specific ideas: About learning/brain development in general (written for students, but applicable to interpretation) Intrinsic motivation, or self-motivation (crucial for maintaining attention or interest) is increased when: 1. There are choices for the learner—content, timing, process, environment, or resources 2. It is relevant to the learner—make it personal—relate to family, situation, love, hopes and desires, health, etc. (Things that make sense and have meaning are most likely to stick.) 3. It is engaging—make it emotional, energetic; make it physical, use learner-imposed goals or deadlines, use positive peer pressure Examples of pattern types Linear repetition Linear patterns repeat indefinitely in any direction along a line Examples: beads on a necklace, woven materials, wallpaper borders, stripes on clothing, zippers, walking footprints, musical rhythms, the meter of poetry, the passage of a day, the changing seasons, cycles Spirals Spirals wrap around a fixed point at a changing distance Examples: spider webs, nautilus shells, watch springs, woven baskets, and coils of rope Many types, but 2 common: Archimedean (like a coiled rope) and the golden spiral (like a snail shell—differential growth due to more room to grow farther away from axis). Branching Branching patterns start from a single point and grow outward in many directions Branching patterns are economical—they reach a large surface area using the shortest path. Formed by organisms, systems, and structures that distribute or collect large volumes of material. Natural systems, especially those involving liquids, have branching patterns. Examples: river systems (water transport), lightning (electrical dissipation), and plants (nutrient, gas, and water transport), circulatory system, roads. Symmetry There are twenty-four two-dimensional symmetries; bilateral/mirror and radial/rotational symmetry are two common symmetries. Bilateral/mirror symmetry: halves that are mirror images. Axis can be vertical or horizontal. Mirror symmetry examples: human body, shapes and/or markings in many plants & animals. Radial/rotational symmetry: repeating pattern around a center point (3 repetitions is minimum). Radial/rotational symmetry examples: starfish, flowers, snowflakes, tile work, basket patterns, kaleidoscopes. Tessellation formations Regular tessellations are made by one repeating shape. There are only three shapes that create regular tessellations: triangles, squares, and hexagons. Irregular tessellations can be made from a variety of repeating interlocking shapes as long as they fit together without gaps or overlaps. Introduction Brain-Based Techniques to Think About When Developing a Program Good Practice Purpose Start with a hook Focuses the audience on the topic Novelty makes the brain pay attention State learning objective(s) ID what needs to be learned Know what they should learn and how they will know they’ve learned it Purpose/Theme Explanation of importance “So what?” Give information, sources, skills Builds interest and established meaning Most important information first Group information logically Body Chunk information Conclusion Relationship to Brain Research Establishes relevance and fosters transfer Practice Review information or practice what was learned Closure Allows participants/ audience time to mentally summarize and internalize new learning Helps audience remember/retain critical attributes Working memory sees a set of data as a single item because of past experience—easier to remember and learn. Enhances sense and meaning to help retention dendrites grow between nerve cells, increase connections and makes the neural network stronger (practice makes permanent) Last chance to attach sense and meaning, thus improving retention. Example Think about the last time you were bitten by a mosquito. During this program you’re going to learn about how habitat conservation helps to control mosquitoes. By the end of the program you’ll know at least 4 ways that your daily routines influence habitat conservation. Habitat conservation is key to human survival. Whatever it is that you want your audience to remember 5 years from now. Group items together when learning a procedure (see next page) Pair the familiar (peanut butter & jelly) Categorize (see next page) Use knowledge to create something, solve a problem, or apply it to another topic. “I’ll be quiet now while you think about (theme)” Thought question, asked rhetorically: “In the next minute, 4 acres of habitat will be lost. What will you do to help slow the pace?” “Think of one or two things you’ll take away from this program.” Chunking Information Group items together when learning something new Group items in a sequence, rehearse mentally, practice o Learning to canoe—what to do when getting in, what to do when moving, what to do when getting out o Learning to identify a plant—what parts to look at—vegetative parts, reproductive parts Create acronyms with familiar words or phrases Categorical chunking Advantages and disadvantages (energy sources, environmental actions, transportation, etc.) Similarities and differences (owls and hawks) Structure and function (parts with different functions—animal cell, short story) Taxonomies biological, learning (cognitive, affective, psychomotor) Arrays (less ordered than taxonomies, based on observable feature. Humans by learning style, personality type; dogs by size, shape, fur length; clothing by material, season, gender) A Few Cognitive Biases A cognitive bias is a pattern of deviation in judgment whereby inferences about the world are made in an illogical fashion. (We all do at least some of these things.) 1. Confirmation bias—we tend to give more credence to people or ideas who agree with our views; similar to ingroup bias 2. Ingroup bias—oxytocin, a neurotransmitter, helps us bond with people in our own group while making us suspicious, fearful, or disdainful of others 3. Neglecting probability—we do not properly assess risk. We tend to feel less safe in an airplane than in a car, even though it is statistically far more dangerous to be in a car 4. Observational selection—we suddenly notice things we haven’t noticed before and assume that the frequency has changed—contributes to thinking that things cannot be coincidences 5. Status-quo bias—we tend to be apprehensive of change, assuming that change might make things worse 6. Current moment—we would rather experience pleasure now and face the consequences later 7. Objects have essences—we often believe that there is an invisible value that an object gets from its provenance (John Lennon’s piano) 8. Symbols have power—we might believe that heavy things are more important, we gravitate toward people and things that share our names or initials, we anthropomorphize 9. Actions have distant consequences—superstitions, rituals, taboos Selected resources Hutson, Matthew. (2012). The 7 laws of magical thinking: How irrational beliefs keep us happy, healthy, and sane. New York: Hudson Street Press. Jensen, Eric. (1998). Teaching with the brain in mind. Alexandria: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Kahneman, Daniel. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. Sousa, David A. (2001). How the brain learns. Thousand Oaks: Corwin Press, Inc. Videos to investigate Fast and slow thinking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JiTz2i4VHFw Selective attention: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IGQmdoK_ZfY