Second Sunday Before Advent, 2013 Feast

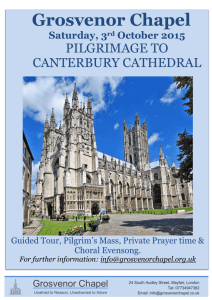

advertisement

Grosvenor Chapel 17th November 2013 – The Feast of the Dedication & Centenary of the Re-ordering of the Chapel by the architect Ninian Comper. John 2.21 He was speaking of the Temple of his body This Temple was not raised up in three days. Yet it was remodelled over a comparatively short period of three years – from planning stage to rededication – to the design of the architect, Ninian Comper. I am not as familiar as I might be with Comper’s work: he designed the east window of the church in Hackney Wick where I was until recently priest-in-charge. That window was destroyed by a V2 rocket in 1944 – a fact which stimulated my curiosity enough to buy what is undoubtedly the best compendium of Comper’s life and work: the beautifully illustrated book brought out in 2006 by your neighbour from Farm Street, Anthony Symondson SJ. The fine photographs capture only a proportion of the literally hundreds of churches in which Comper had a hand, but there is a comprehensive gazetteer at the back of the book – and the entry for the Grosvenor Chapel is one of the most extensive. I quote an extract: 1911 – 1912. Remodelling and planning of the chapel. The Grosvenor Chapel was the first English church of the twentieth century to have the high altar brought forward to be in visual relationship with the congregation. A consistory court case, which questioned the legality of a baldachino, or ciborium, above the high altar prevented the scheme from being completed. Two giant Ionic columns were erected at the east end, which were intended to be the first in a series extending west. Executed work includes altar screen and rood; ciborium over the high altar (only partly erected); altar hangings; decoration in white and gold.1 These notes are as tantalising in what they don’t tell us as in what they do. There was obviously a huge row. Grosvenor Chapel was pushing the boundaries not just of what was possible architecturally, but what was permissible doctrinally. In 1904, a Royal Commission on Ecclesiastical Discipline had been set up to examine deviations from what might be considered the norm of church layout and practice. Some saw this as an 1 Anthony Symondson and Stephen Bucknall Sir Ninian Comper (Reading 2006), pp. 281f. opportunity to hunt out and expose dangerously popish elements that were being introduced in a number of churches. Others saw it as an opportunity to recall the church to the riches of its inalienable catholic inheritance. For Comper, the idea of a ciborium over the high altar was more than a matter of decorative detail. It was a shelter for the radiance of the divine presence of the sort that Saint Peter had so longed to erect for the Lord on the Mount of the Transfiguration. A ciborium, or baldachino, was not just a tent or a canopy, but that part of the church which would draw a worshipping community irresistibly to recognise Christ at the centre of their devotion. Comper compared it to the Parthenon of Athens that had housed the great image of the virgin goddess Athene. Here at the Grosvenor Chapel, Comper’s ambitions for a ciborium were only partially achieved. Elsewhere, however, Anglo-Catholic style and practice was advancing on a number of fronts. By the nineteen-twenties, endeavours to accommodate the divine presence were focused not just on the altar and its immediate surroundings but more precisely on the small confine of space were Christ could be recognised and adored once the bread had been consecrated and our Lord’s coming among us made real. Comper himself envisaged the consecrated hosts being reserved a pyx that would hang from the top of his ciborium. Other Anglo-Catholics pressed for tabernacles to which the consecrated hosts could be borne in procession and from which they might then be taken on solemn occasions, such as Benediction, and revered with as much ceremonial and incense as circumstance allowed. These efforts were assisted by the growing organisational strength of AngloCatholicism during the inter-war period, exemplified by the five great AngloCatholic Congresses which packed out the Royal Albert Hall in 1920, 1923, 1927, 1930 and 1933. After a service at St Paul’s Cathedral and an expertly choreographed simultaneous celebration of mass at twenty London shrine churches, the second Anglo-Catholic congress wound up with an inspirational address by Frank Weston, the Bishop of Zanzibar. “I recall you”, he pleaded, in the last place to the Christ of the Blessed Sacrament. I beg you, brethren, not to yield one inch to those who would for any reason or specious excuse deprive you of your Tabernacles. I beg you, do not yield, but remember when you struggle, remember that the Church is the body of Christ, and you fight in the presence of Christ. I say to you, and I say it to you with all the earnestness that I have, that if you are prepared to fight for the right of adoring Jesus in his Blessed Sacrament, then you have got to come out from before your Tabernacle and walk, with Christ mystically present in you, out into the streets of this country, and find the same Jesus in the people of your cities and your villages.2 There was much in this that was admirable. There was much, too, that was exaggerated and over-contrived. The Congress movement had a provocative, teasing side to it: it pleaded solidarity with the poor but fostered division within the ranks of ordinary church people. It retailed candlesticks for burning “Ridley” and “Latimer” candles; it sent respectful greetings to the pope; it set up a printing house called the Society of Saints Peter and St Paul; it pretended this was the official publisher of the Church of England; and then brought out its reports in a neo-medievalist style. “No student in the history of advertising should neglect the notices of the Society”3, wrote a Church of England bishop, who secretly admired its pluck. But there were some who called themselves Anglo-Catholics who were uneasy with what they saw. “Rupert’s cavalry are dashing too far ahead”4, cautioned Eric Milner-White, the High Church but gentle Dean of King’s College Cambridge, who feared that the church as a whole would repudiate excess. He would rather Anglo-Catholics temper their enthusiasm, engage in dialogue with other Anglicans to show how essentially reasonable their outlook was, and demonstrate that their faith was not some sort of freakish throw-back but the best spirit of this as of every age. Milner-White joined with others of his stamp to take the edge off Anglo-Catholicism, working largely behind the scenes through clubs, committees and college high tables. They produced a fine volume of Essays Catholic and Critical, which I am afraid is largely forgotten today, as well as being instrumental in bringing out the first ever doctrine report of the Church of England as a whole. 2 Report of the Anglo-Catholic Congress (London 1923), p. x. Eric Kemp N.P. Williams (London 1954), pp. 34f. Kemp was Bishop of Chichester from 1974 to 2001. 4 Eric Milner-White Theology, Vol. 8 (1924), p. 160. 3 My favourite of these men, whom I researched for my doctoral thesis, was a Scottish layman called Will Spens who ended up as Master of Corpus Christi College Cambridge and who ran East Anglia from his college study as Regional Commissioner during the Second World War. Spens dearly loved the most elaborate sort of church ceremonial, but would not be seen dead tolerating it in his own college chapel. Using his extensive contacts among the bishops he met at the Athenaeum, Spens devised a scheme whereby advanced AngloCatholic churches could apply for licenses to hold devotions before the Blessed Sacrament. This was ingenious, as well as well-intentioned, but it failed completely to take account of the fractious and boisterous mood among the most advanced Anglo-Catholic parishes, most notably in London. When the then Bishop of London, himself an Anglo-Catholic, attempted to introduce the new rules within his diocese in 1929, twenty-one Anglo-Catholic churches rebelled against his authority. You might have thought, perhaps, that the Grosvenor Chapel was among them. Yet having a retired bishop on the premises undoubtedly curbed any appetite for anti-episcopal rebellion. Charles Gore, whose cope and mitre are somewhere in the building here, was profoundly suspicious of what he saw as Spens’s devious manoeuvrings and over-subtle cast of mind, but he was not himself in his late seventies going to raise the banner of revolt. The Priest-in-Charge at the time, Francis Underhill, was secretary the Federation of Catholic Priests, one of the main sponsors of the Anglo-Catholic Congress movement. Yet he also, in a position of some delicacy, declined to take up the cause. Within ten years, Underhill would himself become a bishop, but his stance ought not to be seen as one of guarded self-promotion. Not least because it helped define a special quality of church life and worship at the Grosvenor Chapel, and because it has contemporary relevance for the situation here today. Frank Weston’s type of Anglo-Catholicism was hot and fiery, rejecting accommodation with liberal and evangelical influences, rejoicing in a kind of beleaguered combativeness, relying much on its inner organisational strength. There are clear parallels with Forward in Faith, which can stage events every bit as impressive – if somewhat smaller in scale – than the original AngloCatholic Congresses. By contrast Will Spens’s type of Anglo-Catholicism was cold and calculating, relying much on the mental capacity for compartmentalising tastes and ideas, refined to the point of exquisiteness, subtle to the point of obscurity. If there is no obvious successor movement to Spens’s and Milner-White’s churchmanship, it is because it worked too carefully and too remotely to leave anything by way of permanent structures, or of disciples fired up for the cause. Both types of Anglo-Catholicism have something to offer, but both have to be rejected in their purest form, which is what Gore and Underhill understood in their different ways back in 1929. Our Catholicism has to be engaged with those other influences inside and outside the church which contribute to its vitality and help build up its life, so it needs an openness to dialogue and a capacity for reason, perspective and critical nous. On the other hand, that engagement itself has got to be real and vital – not desiccated over overabstracted – recognising the depth of the issues at stake and acknowledging how they stir our emotions and cause us variously to shudder or adore. You have it here at the Grosvenor Chapel, both sides – a Goldilocks type of AngloCatholicism; not too hot and not too cold; as it says in your strapline, “Unafraid to Reason; Unashamed to Adore”. It is these twin aims which, I believe, hold the line between those contrasting perils into which Anglo-Catholicism has sometimes drifted – flippancy on the one hand and over-earnestness on the other. We meet together neither as fanatics nor as heartless automata, but we strive for a characteristic type of worship which tempers absorption with lightness of touch. For “I know, my God, that you search the heart, and take pleasure in uprightness; in the uprightness of my heart I have freely offered all these things, and now I have seen your people, who are present here, offering freely and joyously to you”.5 Amen. 5 From the first reading: 1 Chronicles 29.18.