Wake Forest-Sullivan-Stirrat-Aff-Georgia

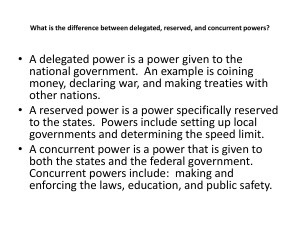

advertisement