mccorklelectures - Puget Sound Chapter of the Oncology Nursing

advertisement

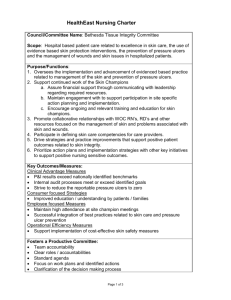

MCCORKLE LECTURES

2013

Challenges in Oncology: “Downstream Fluids for Thought.”

Assessment Guidelines and Standards

Mary Jo Sarver ARNP, AOCN, CRNI, LNC

Oncology & Infusion Services

Northwest Hospital & Medical Center/UW

Infusion therapy, like many things in the world of oncology, has morphed and changed over the years.

Changes are based on technological advances, the discovery of new therapies, and the availability of

multiple vascular access device options. Standards of care and guidelines have been slower in catching

up and some of the downstream effects of providing continuity of care present challenges and

opportunities in every health care setting. Novice nurses in infusion therapy frequently learn by the “see

one do one methodology” hands on mentoring at the bedside or in clinical settings post-graduation.

Seasoned nurses often learn of new products or therapies via short in-services, and reading materials, as

well as policies & procedures updates. As providers of care we dive in to meet the patients and care

facilities needs. Providing safe delivery of care within an expected time frame is often feasible until the

changes exceed the ability to educate during the course of a shift or capture everyone in a society where

full time status and localization to one type of patient or facility is increasingly rare.

Professionally, related to licensing and liability, nurses are held accountable to the standards set forth by

the infusion therapy experts. In 2010 and 2011, the “general” experts in infusion therapy, INS

(Intravenous Nursing Society) and CDC (Center for Disease Control) released new guidelines and

standards of care. ONS (oncology nursing society) participated in writing the INS and CDC guidelines

and updated their specialty specific guidelines related to vascular access devices and chemotherapy &

biotherapy administration. Healthcare providers that perform venipuncture and infuse via vascular

access devices must monitor & maintain devices, educate peers and patients, and are accountable for

knowing and implementing these updated standards and guidelines.

Patient safety is paramount, but where is the evidence showing a specific time frame related to

monitoring provides better outcomes? In infusion therapy, evidence is not in the form of a research

study, but tied to the number of suits filed and settled inside and outside the court room. In the United

States, infusion therapy related suits rank among the highest and most frequently settled healthcare legal

cases outside the court room. More often than not, staff directly involved in the event are rarely aware of

settlements unless the injury is severe and testimony is required. With bad healthcare outcomes, two

things are evident and rarely associated with a specific procedure and therapy.

First is the frequency of assessment and second is the patient’s ability to participate in care and decision

making related to education of the therapy or procedure being provided. Frequency and the content of

physical assessment have been ill-defined and challenging related to many things in healthcare. Policies,

procedures and guidelines specific to infusion therapy are a great example. Often guiding documents are

vague. For example, stating per shift, PRN (as needed), based on the access, based on the fluid being

administered, or periodically. Looking at the definition of a shift alone begs the question as to, is the

assessment time at four hours, eight, twelve, or twenty-four and is the frequency different dependant on

the patient or device?

Specific assessment time frames are ideally tied to the patient’s access, anatomy, infusion being

delivered and response to therapy. Standards and guidelines are generalized in an attempt to provide a

basis for “what the prudent nurse would do.” Experts in the field have taken patient factors into

consideration such as peripheral site location, ability to report and participate, prescribed therapy, health

care setting, age and established standards. Standardization allows for tracking of care and specific

documentation time frames providing a baseline for review of documentation and care provided.

Although not perfect, a safety net for improving outcomes and continuity of care by outlining what is

expected.

My first objective is to provide a brief over view of the new INS position paper: recommendations for

frequency of assessment of the short peripheral catheter site. The first position is related to the

assessment of the site when any IV is infusing. Next, I highlight several key points of the position paper.

Routine assessment: redness, tenderness, swelling, drainage, and/or presence of paresthesias,

numbness, or tingling at the specified frequency

Assessment should minimally include:

Visual assessment

Palpation

Subjective information from the patient and if there is tenderness the dressing removed

and site visualized

If there is tenderness at the site, the dressing may be removed to more carefully visualize

the site

Frequency:

a. At least every 4 hours

Patients receiving nonirritant/non-vesicant infusions, who are alert/oriented and able to

notify the nurse

b. At least every 1 to 2 hours

Critically ill patients

Adults with cognitive/sensory deficits or receiving sedative-type medications and unable

to notify nurse

Catheters placed in a high-risk location (e.g., external jugular, area of flexion)

c. At least every hour

Neonatal patients

Pediatric patients

d. More frequently: every 5 to 10 minutes

Patients receiving intermittent infusions of vesicants

Nurse should advocate for central access administration whenever possible

Peripheral infusion should be limited to less than 30-60 minutes

In addition to visual assessment of the site, a blood return should be verified every 5 to 10

mins during the infusion

Patients receiving infusions of vasoconstrictor agents

Nurse should advocate for central access administration whenever possible

Agents can cause severe tissue necrosis

e. With every home/outpatient visit

Peripheral infusions at home as overseen by home care or outpatient nurses

Patient & family education should include:

What to look for: redness, tenderness, swelling, or site drainage

To check site at least every 4 hours during waking

Ways to protect the site during sleep & activities

How to stop the infusion if signs/symptoms occur

To promptly report to the nurse an organization’s 24-hour contact number

Position Two: Intermittent infusions

Access site with every catheter access/infusion or at a minimum of twice per day

Position Three: Temperatures

Checked at a frequency according to organizational policy/procedure and more often

based on nursing judgment

The possibility of catheter associated bloodstream infection should be considered when

there is fever in any patient with a peripheral IV catheter even in the absence of site redness,

tenderness, swelling, or drainage.

Note that IV pushes are not addressed in the position paper and temperatures rely on organizations to set

time frames.

My second objective is to inspire new and innovative ways to assess central lines and expand our

physical assessment to include a history. The history includes “the life and conditions” the infusion

device is subjected to outside our limited time with patients. Often this approach reveals educational

needs for patients and healthcare providers to prevent infections and preserve the life of the line.

A general history should include:

•

When and where was the central line placed?

•

What type of central line is it and did you receive any paperwork?

•

Who takes care of your line?

•

What type of education did you receive related to potential complications and signs and

symptoms that need reporting?

•

What type of education did you receive related to protecting your line during everyday

activities?

•

Were you provided with a 24 hour number to contact?

Assessment should include:

Bilateral comparison of left to right upper extremities for chest asymmetry and/or contra

lateral circulation (may indicate a venous thrombosis, superior vena cava syndrome, prior

unresolved infiltration / extravasations)

Check for caps, ask “how frequently they are being changed or removed”? “Has one of

the caps ever fallen off”? “What did you do or would you do if it happened”?

Check for clamps and ask, “Were there ever clamps that were removed”?

Flush each lumen, does the patient complain of “whooshing, light headedness, jaw pain,

etc.”

If unable to flush, ask “when was the last time the lumen flushed without difficulty”?

Assess for cracks in the hub/valve/pigtail, leaking at the entry site

Ask “what would you do if fluid was leaking along the pigtail or catheter during flushing

or infusions”?

If it is a valved catheter, where is the valve located (by the hub or at the tip)?

Assess Dressing and catheter from wings to entry site

Note dressing change date and or needle access date greater than 7 days?

Is the dressing dry and intact?

What is the patient doing to keep the dressing dry during or after bathing?

Is there taping around the boarders or skin irritation?

How and where is the catheter secured? Stat lock, steri strips, sutures

Is there gauze under the dressing? If so, how often is the dressing being changed?

Is there a bio patch? Is it applied correctly?

How much of the catheter is exposed? Has it migrated in or out?

Is the catheter under the adhesive portion of the dressing? What are they using to remove

adhesive off the catheter?

Entry site

Erythema

Discharge and/or drainage

Pain with palpation

Pain with ROM

In summary, infusion therapy devices, whether peripherally or centrally located, serves as an access to a

patient’s bloodstream and delivery system for fluids, medications, blood products and or nutritional

support. Often, infusion therapy devices have been defined as the patients life line based on the potential

to save a life. The other side is the potential to cause secondary complications or death during insertion,

improper maintenance and or via infection. Currently there are over one hundred and fifty different

types of devices on the market. The association for vascular access offers a certification exam which

speaks to the complexities and knowledge base. Hopefully, my objective is met and this article provided

a stepping stone related to “fluids for thought” to be used in assessment, documentation and education of

the patient.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------2012

The Pathway to Becoming a Professional Nurse

Nancy Thompson, RN, MSN, AOCNS

I was informed by the Symposia committee that I had been selected for the 2012 McCorkle Lectureship award on a

beautiful autumn Saturday morning that just happened to be my 50th birthday. The timing of the award prompted me

to reflect on my life and career which in sharing with you, I hope will help you to reflect on your own nursing

journey.

I was not one of those little girls who always wanted to be a nurse. My parents were both school teachers and I

probably thought I’d be a teacher too. But in my teenage years, my rebellious side made an appearance and I decided

there was no way I was going to be a teacher. Now in my role as a nurse educator, I spend a good portion of my time

educating nurses and patients so I became a teacher after all. Which lead me to realize that we have to Celebrate

who we are.

Each of us brings our personal backgrounds, gifts, experiences, and personalities to our nursing practice. Rather than

rebel against it, as I initially did, we ought to celebrate the diversity it brings to our profession and to our patients. I

remember learning in nursing theory class about the “therapeutic use of self”. It is defined as the “the ability to use

theory, experiential knowledge, and self-awareness, and to explore one's impact on others”. (Miller-Keane

Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, Seventh Edition. © 2003 by Saunders) The

“therapeutic use of self” doesn’t mean sharing our personal lives with patients but it does mean bringing the essence

of who we are to our nursing practice. This provides depth and sincerity to our nursing practice.

I considered several other health care related careers but nursing is the only discipline that truly treats the whole

person. As Wikipedia states;

“Nurses care for individuals of all ages and cultural backgrounds who are healthy and ill in a holistic manner based

on the individual's physical, emotional, psychological, intellectual, social, and spiritual needs. The profession

combines physical science, social science, nursing theory, and technology in caring for those individuals.” (Wiki)

I remain happy with my choice of nursing and still believe that treating the whole person is one of the greatest gifts of

the nursing profession.

I graduated from Montana State University with my nursing degree, moved to Arizona and accepted a nursing

position in Sun City, Arizona at Boswell Memorial Hospital. Over the next few years I learned how to be a nurse and

I was introduced to two of my career nursing interests. The first of which was Gerontology.

Sun City is a combination of people from all over the country who have moved away from their families to retire in

the southwest and most of our patients were in their 70’s. I facilitated a cancer support group there and became very

fond of these people who shared their lives with me and with each other. This older age group met their cancer

diagnosis with a lifetime of experience. Some had learned much from their lives, had acquired wisdom and

developed inspiring life philosophies and coping skills. And some of them were angry, bitter and lonely. As we age,

our personality characteristics tend to become accentuated as we are shaped by our responses to life experiences.

The older people who were wise and generous had learned life skills and grown from the experiences life had thrown

their way. Those people taught me to “work on becoming the old person that I want to be”. We have a choice.

We can become bitter and angry or we can become thoughtful and generous, and it largely depends on how we

respond to our life challenges now.

The second nursing interest I developed at Boswell Hospital was oncology nursing. There are probably as many

reasons for choosing oncology nursing as there are oncology nurses. I was fascinated by the science of oncology and

I enjoyed the IV skills but it was the depth and openness of the patient to nurse communication in oncology that

captured my heart. For my psychiatric nursing internship in school, I completed Hospice volunteer training and was

assigned a patient. I loved the conversations I had with my Hospice patient. She told me about her life, her regrets,

her accomplishments and her fears. When people are in crisis, they talk about who they really are and what they truly

value.

I love this quote out of the Hospice handbook I received in my Hospice training. It is a child’s mother describing her

daughter’s death.

“But my little girl did have a message for everybody here: the only thing when the chips are down that really matters

is kindness. You can spell it anyway you want. Some people say love, some say compassion but when you act it out,

what is it, its kindness, and that’s the only thing you can give. My little girl didn’t need any more needles, any more

tests or anymore anything. What she did ask was for me just to be with her and hold her, and that’s the message,

when the chips are down what else have you got – its one human being communicating with another.” (A Hospice

Handbook, anonymous)

I cherish the privileged opportunity we have to share with others at this level.

While working as a geriatric oncology nurse, I attended every available education program regardless of the topic. I

learned a lot about gerontology, about nursing, and about various other medical conditions.

The Oncology Nursing Society refers to this as Lifelong learning. It is a crucial step in our pathway that never

ends. As the ONS position statement on lifelong learning states;

Nursing as a profession is called to lead change and advance health. To meet this challenge, nurses must practice a

commitment to lifelong learning. Lifelong learning is the notion that learning occurs along a continuum from

elementary and secondary education to undergraduate and graduate education, lasting throughout the end of one’s

career. (Oncology Nursing Forum, (39) 2, March 2012, pg 127)

Lifelong learning keeps us inspired and motivated as nurses. When you are bored with the conferences that you

usually attend, choose a conference of a different discipline or non-oncology to gain a new perspective on your

patient population.

After a few years I registered at Arizona State University for graduate school. There I learned critical thinking,

writing skills, systems theory and the value of the literature. But most importantly, I learned community health.

Health, including oncology, starts in the community. Community health includes cancer prevention, health care

policy, access to care, lifestyle choices and behaviors. Up to this point, I had spent my entire career working in a

very specialized area of cancer treatment but had ignored the basics behind why people came to be in our clinic.

Florence Nightingale recognized the importance of community health. She stated,

“Every nurse should keep this fact constantly in mind - for if she allows her sick to remain unwashed or their clothes

to remain on them after being saturated with perspiration or other excretion, she is interfering injuriously with the

national processes of health just as effectually as if she were to give the patient a dose of slow poison by the mouth.”

(Notes on nursing, 1860, pg 93)

According to Florence Nightingale, providing basic community health and hygiene is an equally important nursing

function to giving oral chemotherapy. When PSONS commits to community service projects, we are nursing to our

most vulnerable patients and explicitly following the directions of Florence Nightingale.

I became involved with the Oncology Nursing Society, both in my local chapter and later nationally. I was asked to

share the Phoenix chapter presidency with another member. We didn’t know each other very well but we

enthusiastically attended the ONS mentorship weekend which incidentally ONS still offers today. We became

lifelong friends and converts to ONS! We were amazed at all that ONS had to offer and the vision of oncology

nursing that they had.

An important aspect of ONS is that you get out of it what you put in. My involvement with ONS has made me

lifelong friends, opened doors and opportunities I would never have dreamed of, and challenged my thinking and my

nursing practice. Graduate school was necessary for academic skills but ONS taught me how to be an oncology nurse.

My activities in ONS have provided me a network of oncology nurse colleagues from all over the country. Not only

are they wonderful friends, but they are a wealth of wisdom whom I rely on for help and assistance every day. Don’t

underestimate the value of your professional organization; they have a lot to offer.

ONS recommends developing professional mentors. I’ve had 3 really amazing nurses’ help guide my journey. The

first is Debi Boyle. Debi was more of a role model than a mentor and served as my vision for the embodiment of

oncology nursing. All I could think of the first time I heard Debi speak was “Wow, I want to be LIKE THAT!”

Then I worked with Betty Gibson in Arizona who taught me about public health and education, about working within

health care systems, and about being authentic with patients. Betty knew how to get things done in a system by

knowing what to say and, just as importantly, what NOT to say.

When I moved to Seattle, I met Linda Hohengarten who taught me how to be a clinical nurse specialist and so much

more. Linda taught me the importance of people and relationships and gave me the space to develop those

relationships and I will be forever grateful for that.

Maybe you have a mentor; maybe it’s time for you to BECOME a mentor. My mentor Betty said, “I like to think

that mentoring is really a 2-way learning opportunity.” Many oncology nurses have a lot of knowledge, both clinical

and professional that younger nurses would derive great benefit from.

I applied for everything ONS offered and was accepted into the ONS/BMS Ambassador 2000 program. It was

described as;

“A media outreach program that promotes the role of the oncology nurse to advance the public’s knowledge about

the supportive care of individuals with cancer. Through the dissemination of this information, the oncology nurse

becomes the advocate for individuals with cancer, the public, and the oncology nursing profession.”

Professional educators taught us presentation and publication skills, how to interact with the media and tips for

advocating in the political arena. At the end of the program, I had gained professional skills, fabulous new

colleagues, some great stories and a couple of valuable lessons.

First, Patients need nurse advocates. They depend on us to be their voice. We advocate for patients by questioning

medication orders, calling for ethics consults, locating financing, writing to legislators about health care issues,

requesting interpreters and so much more. This is a vital role of nursing.

Second, Supportive care is the core of oncology nursing. This is where we truly add value to cancer care. Patients,

who get great supportive care, stay on treatment, receive full doses, and experience the best outcomes and the highest

quality of life. Supportive care includes symptom management, palliative care, referrals to other members of the

team and patient education. It means taking care of the whole patient and is what oncology nurses do every day.

Another ONS program that I attended was the ONS/GSK Leadership Development Institute. The goal of this

program was to “prepare oncology nurses to LEAD the transformation of cancer care.” This program challenged

me to think about my career and my professional goals. The Institute faculty raised questions that I struggled to

answer:

Why did you go into nursing?

Why do you stay?

What makes it a good day?

How do you keep going at the low moments?

What is your personal mission statement?

How do you add value to cancer care?

In 2000 I became the coordinator for the Sun City site of the Alzheimer’s disease Anti- Inflammatory Prevention

Trial (ADAPT). This was a big move personally as it was away from Oncology but I was attracted to it as it was a

very prestigious trial, funded by the National Institutes of Aging, and coordinated through John Hopkins University.

Our Sun City team was small and new to clinical research studies of this magnitude. The other trial sites were all

prestigious universities with well-known reputations and mature clinical research programs. The staff from the other

sites literally snickered at our Sun City team and probably expected us to fail.

When I left that position, our site had the highest recruitment and had received a commendation for the quality of our

data. This experience taught me that; It’s not about where you work, it’s about the work that you do. There is a

lot of competition in health care among health care institutions with mergers and affiliations happening every day.

To us in the front line of patient care, none of that is important. It doesn’t matter if you work in a large prestigious

institution or in a small community hospital or clinic. What is important is your relationship with your patient, your

therapeutic use of self, and the supportive care you provide to patients every day.

Much as I enjoyed my clinical research experience, I missed oncology nursing and the Pacific Northwest, so I

accepted a position at the Swedish Cancer Institute as the outpatient clinical nurse specialist. Here I have learned

many things but maybe the most important of these is: Keep your eye on the patient and you’ll never lose your

way.

It’s very easy to get distracted by hospital politics, conflict between nurses and with other disciplines, budget

problems and short staffing. It’s easy to complain about our work environment and to forget our purpose and our

goal. But if we keep our focus on what’s best for the patient, we will never lose our way.

Dr. Albert Einstein, our medical director at the Swedish Cancer Institute retired in January. In his final note to the

staff he said,

“We can put together a number of ingredients to provide high quality cancer care but the ultimate essential

ingredient is a staff of committed dedicated individuals working together as a team to make sure that each and every

patient receives the best medical care and service possible. “

When we all work together as a team, advocating for our patients, providing supportive care, treating each patient as

a whole person I believe we change people’s lives, we change the health of our patients and our community, we

change our world, and we cure cancer. That is why I became a nurse, that is why I get up every day to come back

and do it again, and that is what makes it a good day for me.

It’s been a far more fulfilling journey than I had ever dreamed possible. I’ve learned more, accomplished more, had a

lot more fun, met the most amazing people, made wonderful friends, and hopefully I’ve added value to patients’

lives, to the community and to cancer care.

And I wish the same for all of you.

2011

Adolescents and Young Adults:

Adrift in the Sea of Cancer Survival

Linda Cuaron, RN, MN, AOCN

Cancer treatment for children and adults today may be viewed as a “sea of success” with greater

awareness, earlier detection, and discoveries in genomics and personalized medicine leading to the

potential for cancer to become a chronic illness. Significant progress is being made in the area of

clinical cancer research, surveillance and prevention, resulting in cancer incidence and cancer death

rates that have declined in the United States.

The CDC defines a cancer survivor as anyone who has ever had cancer, from the time of diagnosis

through the rest of their life. There are 12 million cancer survivors in the United States today, according

to new statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and over 28 million

worldwide. That is an improvement from the official US figure in 2007 of 11.7 million survivors, 9.8

million in 2001 and just 3 million in 1971. About half of the nation’s cancer survivors have had either

breast, prostate, or colorectal cancer and slightly more than half are women. About 7 million survivors

are 65 or older, and 4.7 million were diagnosed 10 or more years earlier. Earlier detection,

improvements in diagnosing cancer, and more effective treatment and follow-up are some of the reasons

for the increase in the number of cancer survivors over the years.

Adrift in the Sea of Cancer Survival

However, the story is not as bright for the adolescents and young adult (AYAs) cancer patients and

survivors of childhood cancer. Survival improvement trends show a worse prognosis for AYA’s

diagnosed today than 25 years ago. Survival figures for children who have had cancer have improved

by 1.5% per year for children younger than 15 and adults older than 50 years, but cancer survival has

improved by less than 0.5% per year in 15- to 24-year-olds. This is in contrast to statistics seen at the

beginning of the last quarter century when the diagnosis of cancer in 15 -29 year olds carried a more

favorable prognosis relative to cancer at other ages. That is no longer the case, and moreover, cancer

survival has not improved at all in 25 to 34 year-olds. This deficit is increasing with longer follow-up of

survivors. These deficits appear to be global, and not just seen in the US. Figure 1 depicts the stark

differences in 5-year relative survival for invasive cancer based on US Seer data from 1975-1997.

The world of traditional cancer care is well-developed with multiple organizations, cooperative research

groups, advocacy and supportive groups, and numerous sub-specialties. Similarly for pediatric cancer

patients there are defined research organizations, hospitals, specialists, and palliation and survivorship

programs. There is active work in genetics and genomics for adult and childhood cancers, but this is

limited for the AYA group.

AYA Cancer Survivors and the Newly Diagnosed

There are two groups of AYA patients that warrant concern. There are those who are survivors and are

at increased risk for medical complications and/or cancer recurrence, and those who will become newly

diagnosed during the ages of 15 – 29. It was reported at last year’s American Society of Clinical

Oncology (ASCO) meeting that long-term risks for cardiac problems were found among children and

adolescent cancer survivors who were treated with anthracyclines and/or chest radiation. They were 6

times more likely to develop congestive heart failure than their siblings who did not have cancer.

Further, it has been shown that the late effects of childhood cancer substantially reduce life expectancy.

The incidence in cancer in the AYA age group increased steadily during the past quarter century. We

don’t know why……behaviors – smoking, sun exposure; environment; obesity, tumor biology,

decreased surveillance?

The AYA group represents about 6% of all new cancer diagnosis which means 1 in every 168

Americans between the age of 15 and 29 will develop cancer. This group is 8 times more likely to

experience cancer than those under the age of 15. Seer data showed that males in the 15 -29 year age

group are at higher risk than same age females for developing cancer, with the risk directly proportional

to age. Non-hispanic whites have had the highest incidence of cancer during this phase of life and

Asians, American Indians and Alaskan Natives, the lowest. The prognosis for males was worse than for

females, and African American/Blacks, American Indian/Alaska Natives had a worse prognosis than

white non-Hispanics and Asians.

The incidence of cancer in AYAs is increasing exponentially as a function of age, with approximately

half of the AYA group in the 25-29 year age range. With the exception of invasive skin cancer due to

ultraviolet light exposure, the majority of cancer types occurring in AYAs aged 15 to 29 years are not

readily explained by either carcinogenic environmental exposures or family cancer syndromes. The fact

that the AYA group has an exponential risk of developing cancer as they age suggests a possible

molecular basis resulting in a basic carcinogenic exposure that is age-dependent, such as telomerase

shortening or a mutation-to-malignancy rate that increases constantly with age.

The majority of research has focused on clinical trials for pediatric patients with an age limit for

participation of 18. Even when eligible for pediatric clinical trials, AYA patients are often treated by

adult oncologists. What is the result? Significantly worse outcomes and an event-free survival of 38%

versus 64% were seen when adolescents were treated on pediatric protocols at pediatric institutions.

Pediatric cancer patients had a greater than 75% event-free survival on the same protocols. When

clinical trials are not an option, AYAs with “adult” types of cancer, such as melanoma, breast cancer,

and colorectal carcinoma, may need the treatment expertise available at adult cancer centers.

“There is no other patient age group for which the time period to diagnosis is longer, clinical trial

participation lower, and fewer tumor specimens are available for translational research” (Bleyer, 2006).

The lack of clinical trial participation is particularly problematic with only 1-2% of all 20-29 year olds

with cancer participating in a therapeutic clinical trial sometime during their cancer experience. A

correlation exists between the level of clinical trial activity and improvement in survival prolongation

and mortality reduction. These factors explain much of the deficit in translational research and the lack

of tumor specimens available for studies assessing molecular and cellular mechanisms of cancer in

AYAs.

Prevalence and Distribution

of Cancer in AYAs

The top ten cancers affecting this age group are lymphoma, leukemia, melanoma, female genital cancer,

cancers of the breast, thyroid, sarcoma, testis, colon, and brain. The distribution of cancer differs by age

group with a higher incidence of hematologic cancers (40%) in the 15-19 year olds that decreases to

20% in the 25-29 year olds when melanoma becomes the predominant cancer (see figure 2).

AYAs are vulnerable to the challenges of an immature coping repertoire. They may have a limited

ability to look beyond the present, and the perils of uncertainty. The AYA years are a time to focus on

building the skills and a personal foundation that will support them as they become adults. This is the

time they learn to adapt to newly emerging intellectual abilities, to balance the influence of peers and

family, and to adjust to society’s behavioral expectations. This is the time when they internalize a

personal value system, investigate their sexuality, and prepare to become contributors to society, prepare

for their future and independent adult roles.

Uncertainty

Uncertainty can play a large role in the AYA cancer experience. Mishel’s “Uncertainty in Illness

Theory” provides a framework for looking at the AYA experience. This theory states that uncertainty in

illness situations can be experienced in four ways;

• ambiguity about illness and

symptoms,

• complexity of systems of care,

• lack of information about diagnosis

and serious of the illness, and

• the unpredictability of the disease.

The elements of this model ring true when reviewing of the literature about the AYA with cancer.

Consider the issues impacting a “survivor” of childhood leukemia. An 11-year-old female diagnosed

and treated in 2000. She may have received cytarabine, daunorubicin, etoposide, and prednisone.

Today she is 21 years old, a college grad but unemployed and uninsured and cancer-free. She may delay

or not seek health care for symptoms associated with prior chemotherapy because she does not associate

current symptoms with prior damage from chemotherapy, or she may not have the funds. She may

minimize or deny her symptoms. She might find the process of getting an appointment with a specialist

too daunting to pursue or she might actually fear that her cancer has returned and that she will not

survive further treatment. Because of her exposure to certain chemotherapy agents she is at risk for

cardiac damage, nerve damage, secondary malignancy and infertility. Add to that the potential for

insurance denial because of pre-existing condition and the challenges are overwhelming.

Long-Term Concerns

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study was a cross-sectional survey of 635 consecutive survivors

(approximately 5%) drawn from a group of 12,156 participants age 18 years or older, who at an age <21

years had survived 5 years from diagnosis of cancer. This study revealed that only 35% of AYA cancer

survivors realized that they could have significant health problems after being treated for cancer. The

survey asked about their knowledge of their cancer diagnosis and other associated therapies in a 3- to 5minute telephone survey. Overall, only 72% accurately reported their diagnosis while 19% were

accurate but not precise. Individuals with central nervous system (CNS) cancer and neuroblastoma were

more likely not to know their cancer diagnosis. The accuracy rates for reporting their treatment history

were 94% for chemotherapy, 89% for radiation, and 93% recalled that they had a splenectomy. Among

those who received anthracyclines, only 30% recalled receiving daunorubicin therapy and only 52%

remembered receiving doxorubicin therapy, even after prompting with the drugs’ names. When

prompted with choices of names of different diagnoses, 72% of the participants accurately reported their

diagnosis with detail and 19% were accurate without detail. When asked the question of whether past

therapies could cause a serious health problem with the passage of time, 35% of participants responded

yes, 46% responded no, and 19% did not know. Only 15% responded that they ever received a written

list of their disease diagnoses and treatment, including names of chemotherapy agents, to keep as a

reference in the future.

Developmental Issues

Caring for cancer patients of any age is never easy. But for the AYA there are unique challenges.

Certainly there are biomedical and genomic issues which are not yet fully understood. Cancer in the

AYA group has the greatest heterogeneity. But for any adolescent or young adult, regardless of health

status, this is a time of rapid change related to development and emotional health, a time when they ask

“who am I”. It is a time for examination and integration of values and beliefs with those of society as

well as a time to develop independence. This is when they form meaningful relationships outside the

family by establishing strong attachments to their peer group. Even as they strive to develop

independence they vacillate between dependent and independent functioning

Add cancer to the mix and you will find adolescents who are at risk for loss of control, loss of

independent functioning, devastating impact of alterations in body image, isolation from their peer

group, loss or change in goals for the future. Today there are many on-line forums, blogs, and websites

to help the AYA and the health care provider. Some of the comments from an AYA blog, when asked

to compare “real live” vs “cancer life” reveal their reality:

• “Doctors don’t trust me, I don’t trust

them”

• “I had to deal on my own with

things that no one may age knew

anything about”

• “I met a grand total of 4 young adults

in 18 months, all but one died”

There are key developmental milestones that are profoundly influenced by the cancer experience.

During adolescence and into young adulthood, the focus is on committing oneself to concrete affiliations

and partnerships. While in this developmental stage the young adult builds on the identity established in

adolescence. A young adult learns to develop reciprocity in an intimate, interpersonal relationship in

which it is possible to merge his or her identity with that of someone else without fear of losing the

sense of self. This individual begins to strive toward financial, psychological, and physical independence

and autonomous living. During cancer treatment, the young adult with cancer faces threats to achieving

these key developmental steps that include altered body image, isolation from school/work/community,

loss of ability to maintain or develop intimacy with significant others, change in a timeline for achieving

goals, and a loss of independent functioning.

Clinical Trial Participation

Historically, 90% of children younger than 15 years with cancer are managed at institutions that

participate in NCI-sponsored pediatric trials but only 21% of adolescents 15 to 19 years old participate

in clinical trials with far lower estimates for 20- to 29-year-olds. This probably reflects the fact that the

vast majority of AYAs with cancer are treated in community- based settings by oncologists who do not

regularly enroll patients onto NCI-funded clinical trials. Experts argue that this deprives AYAs access to

contemporary treatment approaches and clinical expertise that could improve outcomes and

consequently see increasing enrollment of AYAs on clinical oncology trials as a critically important

strategy for improving survival. The decreased number of AYAs participating in clinical trials also

results in under-representation of their tumor tissue in the national tumor banks. Without blood and

tissue from the cancers that affect AYAs, scientists are unable to advance our knowledge about these

types of cancer.

Research is needed to understand how these cancers differ in AYAs in terms of tumor initiation, their

biological features, and how they may vary in treatment response. Is there a difference in the AYA for

susceptibility to cancer and tolerance of therapy?

Fertility

Certain types of chemotherapy and radiation can put females at risk of acute ovarian failure or premature

menopause. These include total-body irradiation (TBI), and chemotherapy regimens containing highdose alkylators. Males are at risk of temporary or permanent azoospermia resulting in infertility from a

wide variety of chemotherapy regimens, TBI and radiation to the gonads (Levine et al., 2010).

Preventive measures should always be taken when possible. Shielding should be utilized when possible

to reduce scatter radiation to the reproductive organs. Other methods must be accomplished prior to

initiation of cancer treatment. These include for males, cryopreservation of sperm through banking,

testicular tissue freezing, or testicular sperm extraction. Strategies for females include embryo freezing,

egg freezing, and ovarian tissue freezing. Except for ovarian tissue freezing, the strategies for women

involve multiple challenges. Embryo cryopreservation, for example, requires several weeks of hormone

stimulation of the ovaries which may delay the initiation of treatment. Additionally, estrogen

stimulation can introduce additional risks to the female patient newly diagnosed with cancer.

There are also practical and ethical considerations and barriers to address. Unfortunately, according to

the NCI, fewer than 50% of oncologists follow national guidelines on fertility preservation published by

ASCO in 2006. Oncologists may lack knowledge about fertility preservation techniques and guidelines

and lack awareness of appropriate referral sites. There may be underlying concerns about the potential

delay in treatment posed by fertility preservation. It is the responsibility of the health care team to be a

key stakeholder in the preservation of fertility for their patients. Education, support, and planning are

critical to fertility preservation in the AYA at the time of diagnosis. It is recommended that cancer

centers create linkages to specialized teams to provide guidance to the AYA of either gender. It is

critical to plan ahead. If your facility does not have a plan in place today, research the ASCO guidelines

and develop a plan.

Key Components to a Successful

Program for Adolescents and

Young Adults

In 2005-2006 the NCI and the Lance Armstrong Foundation sponsored the Adolescent and Young

Adult Oncology Progress Review Group (PRG) who created the directive to develop standards of care

for the AYA patient with cancer (Zebrack et al., 2010). Their position statement lays the foundation for

creating nationally accepted criteria and standards of care for practice, which would lead to the

development of formal, certified training programs for the AYA healthcare practitioners. They

determined that “quality care for AYAs depends on four critical elements;

• Timely detection,

• Efficient processes for diagnosis,

initiation of treatment, and promotion of adherence,

• Access to health care professionals

who possess knowledge specific to

the biomedical and psychosocial

needs of this population, and

• Research that will ultimately derive

objective criteria for the development of AYA oncology care.”

Timely Detection

At the helm of the lifeboat to improve clinical care for AYAs with cancer or survivors of cancer is the

oncology health care team. The interval from onset of the first cancer-specific symptom to the first anticancer treatment is called “waiting time” and is longer in AYAs. The time to diagnosis is longer in

AYAs than in children. The “waiting time” may be influenced by factors related to the individual, the

health care system or the disease.

Make a commitment to increase awareness and education so that delays in diagnosis can be avoided.

Maintain a high index of suspicion for late effects of anti-cancer therapy or recurrence in cancer

survivors. Avoid failure to recognize cancer-related symptoms or recurrence of cancer. Be aware that

AYAs often deny symptoms, are too embarrassed to report them or attribute them to psychosomatic

manifestations.

Efficient Processes for Diagnosis,

Initiation of Treatment, and Promotion of Adherence

Encourage and assist AYAs to seek care at a comprehensive healthcare center. Know that there are very

few known causes of cancer during early adulthood and it “just happens” regardless of the health of the

person. Realize that AYAs are least likely to have adequate health care insurance and that they should

not allow themselves to “age out” of insurance.

Convey that what is done at the time of cancer diagnosis is important and that the best outcome is

determined by the initial evaluation and therapy. Optimal cancer management means doing it right from

the start! Provide social and emotional support, inquire about social needs at time of diagnosis. Refer to

a social worker or mental health professional as indicated.

Access to health care professionals who possess knowledge specific to the biomedical and psychosocial

needs of this population

Plan to provide adequate social support and prepare for fertility conservation. Help to reduce risk of

medical complications following treatment by providing a summary of the diagnosis, types of treatments

provided (including surgical procedures, names and doses of anti-cancer agents and amount of radiation

delivered).

Be aware of the medical complications of cancer treatment in AYA cancer survivors. Provide riskbased survivorship care and symptomatic surveillance for late effects of cancer therapy. Don’t fail to

educate regarding health promotion, wellness and cancer prevention (diet, physical activity, stress

management, smoking cessation, sun protection). Have a plan for transition of care for survivors

entering young adulthood.

Comprehensive Cancer Research

Once diagnosed, suggest clinical trials. Help the AYA find centers that participate in trials suitable for

their age. Once enrolled in a clinical trial, the AYA needs understanding and support in order to best

adhere to the trial’s requirements. Refer patients to a center with NCI funded clinical trials, or refer to

oncology center that has an AYA focus and environment.

Ask the Patient!

A review of AYA responses to the question of what they would want to see in their cancer treatment

program provided insights and suggestions that center around peer interaction and developmental tasks.

• “Break the rules on my visiting hours, if my friends can come at 8:30 p.m., let them in.”

• “Do not comment about my diet, I have cancer, I’m in the hospital. Heart disease is not my main

concern. If I want McDonalds, let me have it.”

•“I want my oncologist to think of me in terms of my whole “person”, not just my cancer. I have a life,

and I want to live it.”

• “I want you to talk to me about sex. I may be too embarrassed to bring it up, so I’m begging you to.”

• “Tell me the truth, even if it’s bad or scary. Let me know if it’s going to hurt.”

•“Figure out a way to let me have Facebook! It’s my lifeline to the outside world.”

When asked, “Where did you want support but did not find it?” the AYAs identified childcare issues,

financial issues, health insurance navigation, access to clinical trials, a place to study or work at the

hospital and information about fertility and sex.

Ferrari et al, (2010) describe key elements to consider when starting an AYA program. These include:

• Access to the newest Children’s

Oncology Group protocols

• Collaboration with adult institutions

• Links to organizations involved in fertility preservation

• Close monitoring of patients to encourage treatment adherence and clinical trial participation

• Group adolescents on the inpatient unit in designated rooms together, when possible

• Group adolescent patients into designated clinic times

• Convert clinic playroom to teen room during this time

• Engage adolescents in monthly support groups held during clinic

• Engage parents in monthly support groups held during clinic

Remember that adolescents with cancer experience multiple distressing symptoms including pain, nausea,

appetite changes, mood disturbances, sleep disturbances, and fatigue. Fatigue has been identified as the

most prevalent and distressing symptom experienced by adolescents with cancer and places an extra

burden on patients trying to participate in normal activities during treatment.

Research, Support & Advocacy

There is a lifeboat standing by, thanks to the support of The Lance Armstrong Young Adult Alliance, the

Comprehensive Cancer Center Adolescent and Young Adult (AYA) Coalition - National Cancer Institute

of the National Institutes for Health and many independent non-profit groups such as the “I’m too young

for this” Foundation, Cancer Care “The Stupid Cancer Show” and Planet Cancer.

Is that a Lighthouse Ahead?

There has been significant increase in awareness of the AYA cancer survival gap since NCI, SEER and the

Children’s Oncology Group published an epidemiological monograph in 2006. There has been research

primarily conducted by oncologists, oncology nurses, pediatricians and psychologists. Research has been

focused on identification and description of the issue but there is much more to do. Fortunately there are

dedicated funding sources and the issue “fits” with ONS research objectives.

Call the Pilot!

Is it time for an AYA Navigator? Evaluate the way you provide care and services to the adolescent and

young adult. Would an AYA Navigator provide the missing link necessary to help “bridge’ the AYA

survival gap? Consider creating or adopting pathways and standards of care for this age group. With an

increased awareness of the issues surrounding the care and treatment of this unique group a dedicated

navigator could make a significant difference in their cancer treatment outcome.

Take the Helm, Mate!

This is a call to action. The problem is significant and well-defined. Oncology nurses are well-suited to

take the helm in the development of nursing care guidelines and programs. The Live Strong-NCI strategic

plan included a call for core competency curricula and continuing education programs for the AYA group.

Education on the issues related to appropriate care of AYAs with cancer is a need that has been identified.

Prepare for fertility preservation of AYAs who trust you with their cancer treatment. Utilize technology to

educate, support, and promote adherence. Be aware of developmental issues that underlie the responses

and behaviors of the AYA with cancer. Familiarize yourself with the many internet resources that AYAs

are utilizing, and participate where you can. Embracing the technological tools of adolescents and young

adults may provide health care providers with powerful instruments to reach and support the AYA

survivors and those undergoing cancer treatment. Remember that for most oncology practitioners

oncology care is a disease of the aging population and oncology culture is not geared to the culture or

communication styles of the young…yet.

References

Bleyer A, O’Leary M, Barr R, Ries LAG (eds): Cancer Epidemiology in Older Adolescents and Young

Adults 15 to 29 Years of Age, Including SEER Incidence and Survival: 1975-2000. National Cancer

Institute, NIH Pub. No. 06-5767. Bethesda, MD 2006.

Butow, P., Palmer, S., Pai, A., Goodenough, B., & King, M. (2010). Review of adherence-related issues

in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(32), 4800-4809.

Ferrari, A., Thomas, D., Franklin, A., Hayes-Lattin, B., Marcarin, M., van der Graff, W., & Albritton, K.

(2010). Starting an adolescent and young adult program: some success stories and some obstacles to

overcome. Journal of clinical Oncology, 28 (32), 4850 -4857.

Kazak, A.E., DeRosa, B.W., Schwartz, L.A., Hobbie, W., & Ginsberg, J.P. (2010). Psychological

outcomes and health beliefs in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer and controls.

Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28(12), 2002-2007.

Kondryn, H.J., Edmondson, C.L., Hill, J.W., & Eden, T.O. (2009). Treatment non-adherence in teenage

and young adult cancer patients: a preliminary study of patient perceptions. Psycho-Oncology, 18(12),

1327-1332.

Levine, J, Canada, A., & Stern, C. (2010) Fertility preservation in adolescents and young adults with

cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 28(32) 4831-4841

Manne, S.L., Jacobsen, P.B., Gorfinkle, K., Gerstein, F., & Redd, W.H. (1993). Treatment adherence

difficulties among children with cancer: the role of parenting style. Journal of Pediatric Psychology,

18(1), 47-62.

Morasso, G., DiLeo, S., Caruso, A., Decensi, A., & Contantini, M. (2010). Evaulation of a screening

programme for psychological distress in cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 18(12), 15451552.

Smith, M., & Hare, M.L. (2004). An overview of progress in childhood cancer survival. Journal of

Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 21(3), 160-164.

Taddeo, D., Egedy, M., & Frappier, J.Y. (2008). Adherence to treatment in adolescents. Pediatric Child

Health, 13(1), 19-24.

Zebrack, B., Bleyer, A., Albritton, K., Medearis, S., & Tang, J. (2006). Assessing the health care needs

of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors. Cancer, 107(12), 2915-2923.

2010

The Patient’s Voice

From the Kitchen Table to the Clinic

Donna L. Berry PhD, RN, AOCN, FAAN

McCorkle Lecture 2010

This lectureship started in 1987 as a special tribute to Ruth McCorkle, a founding member of PSONS. This

award is given in recognition of a member’s significant contribution to cancer nursing. The chapter

member is nominated by other chapter members and selected by the symposium committee.

The face-to-face time we spend with our patients in the clinic and the hospital is a small slice of life

from their perspective. The cancer journey and experience is much larger than what we observe in our

clinical settings. An individual’s experience is, metaphorically, more relevant to what happens at the

kitchen table than what happens in our institutions. In order to provide excellent navigation and

guidance, we need to find out what that conversation and experience is all about and address the areas

where help is needed.

In 1989 and 1990 when I was conducting my dissertation research, I was talking to a group of men and

women who each had had a diagnosis of genito-urinary cancer. I interviewed them about what it was

like to go back to work after their cancer diagnosis. I expected to hear a lot of complaints and a lot of

sadness. I heard some of that, but I also heard stories about the benefits of going back to work; how

normal it made them feel. What an important lifeline their job was for them! And interestingly, the men

who had prostate cancer reported that going back to work gave them an opportunity to listen to their

colleagues and co-workers talk about their experiences with cancer. These conversations helped these

men understand that they weren’t alone.

During my research I heard other important things as I listened to their stories. One of the amazing

things I heard was what a terrible and terrific decision it had been to choose a treatment.

Prostate cancer is somewhat unique from other cancers because we don’t have large medical clinical

trials that tell us what is the best treatment overall. As I talked to these gentlemen, I realized we didn’t

know what we didn’t know about the decision-making process. What I did know was that prostate

cancer is the most common cancer in men. And survival rates and complication rates of treatment are

not easily interpreted because of the lack of randomized trials. They shared their stories about how they

were going about making their decisions and sometimes there were rather unexpected decisions.

Here are some examples. “I was told by the doctor that I couldn’t lift anything for six weeks.” That was

going to interfere with this gentleman’s job. He didn’t have six weeks of vacation or sick time and he

had a very physical job. His job required that he lift buckets of dirty mop water and vacuum a very large

library. He couldn’t chose surgery and be out of work for six weeks.

Another man said, “The thought that I can cure it with surgery; that took precedence.” So for him,

having some assurance that removing all the cancer cells was important. “More important to me than

getting you know—preserving sex—sex life.” So he was not worried about impotence as a complication

from either surgery or radiation.

Another man said, “I think the seed implant is good in my mind; the number one option at my age. And

that’s the first thing my business associates said. He said, at our age, seed implant is what you do.”

And finally, one of the men told me, “I was going to tell the doctor that I wanted to go with the best they

had. What would be the best for me?”

These interviews led me to the essence of the intervention I would eventually develop. Men were

balancing their age and other personal factors against the side effects of different treatments. They

would then come to a decision, sometimes based on what happened in 1960 to their uncle, or sometimes

the decision may have revolved around what was going on at work. It was always about them; about

their personal factors. The medical factors didn’t help them with their decision in the same way.

In other cancer diagnoses, we also have rational people, sometimes making irrational decisions based on

myths or lack of understanding. And this includes all kinds of decisions that need to be made; ranging

from whether I take my medications at home, to when to place a parent who has progressive dementia in

assisted living. These scenarios emerge where there’s no one definitive clinical action for the clinician

to recommend because it has to do with personal factors that are unique to the individual.

For people with healthcare concerns, (including all of us) there often are menus of options. Each option

has its own set of potential outcomes and uncertainties. Informed consent and patient education

materials primarily present only the medical facts for these options. They can’t present to the patient

their own personal factors. We provide reams of data and information about the treatment choice, and

then we place the burden, or the opportunity, for the decision on the individual and their family. Once

these treatment decisions are made, our patients may still be facing the greatest challenge of their lives,

and all of it taking place in the greater context of their lives.

So I want to share more with you regarding what people go through in the cancer experience. Our

patients become experts in their own symptoms and quality of life concerns. And it’s our responsibility

as clinicians to offer the opportunity for patients to report their experience. And yet we’re faced with

shrinking resources including fewer clinicians with limited time to spend with patients. We are losing

time for comprehensive interpersonal interactions with outpatients; yet that patient’s experience,

particularly reliably and systematically reported symptoms of treatment, is an essential component upon

which our assessment, diagnosis and treatment plan are based.

So starting ten years ago, I and others were compelled to develop a very practical method in which we

could gain information about symptoms and quality of life and quickly review this for the clinical visit.

A method was needed for rapidly understanding what was problematic and what was not, so we could

immediately focus on the problems without going through twenty questions to get to the problem. This

would save some time while making sure our patients have the chance to report their symptoms and

quality of life issues.

This solution was developed in 1999 with direct care oncology nurses at the University of Washington

Cancer Center. We established a very dynamic research team of clinicians from three different

disciplines, including informatics specialists, and graduate students which resulted in a randomized

clinical trial conducted from 2004 to 2007. The purpose of that trial was to compare the clinical impact

of having an electronic self-report assessment summary output available to the clinical team versus usual

care. We tested this in all ambulatory services, focusing on whether or not we could make a difference

in the communication of symptoms, therapies that were recommended and the referrals made for these

problematic symptoms and quality of life concerns.

The patients used touch-screen computers that were easy to navigate and had very easy-to-use interfaces.

We asked them questions about their symptoms and quality of life. We asked them to give numbers to a

lot of things, but we also had a question like this, “Please type in the two most important concerns or

issues that we should address first with you and anything else you want to tell us about which we

haven’t covered here.” We wanted to know what was so bothersome to them that we should start with

that issue. Within a second, the program could generate a report for the clinicians. In a sixty-second

glance, that clinician could know exactly what problems were important to the patient.

At the end of four years we had complete data for 590 patients and we had an audio recording of their

visit with their clinicians. We scored those 590 audio recordings very carefully. We found that

symptoms and quality of life concerns were addressed significantly more often when the clinicians had

the summary and more often when their issues were at a moderate to severe level..

I’m going to give you some other examples of things that we discovered from this study. We found out

that for transplant patients, financial issues were a very big concern. You can just hear this being talked

about at the kitchen table, can’t you? For example: “Not only are we having to deal with cancer; my

family has to go out and raise money just so I get treated for it.”

We found very interesting dialogues in the audio-recordings regarding sleep disturbances. Of those 590

patients, 120 of them reported serious insomnia. They had said either “I have difficulty getting to sleep

and staying asleep almost every night” or “It’s almost impossible for me to get a good night’s sleep.”

The majority, 81 of 120, had a conversation with their clinician during the visit and, for the most part,

once the clinician talked to the patient the problem was addressed. For 27 of the 81, the clinician

addressed concomitant symptoms, saying “let’s see if we can work on your pain so it will help your

sleep”. A small percent (15%) of clinicians, (but a should-never-happen-percent) changed the subject

when the patient brought it up during the clinic visit. And if you add that to the forty one visits in which

the problem wasn’t addressed by anyone at all, we find that about half of 120 patients with serious

insomnia received no attention to the problem at all. What’s wrong with this picture? These are the

things that our patients are trying to deal with in their homes that are part of their whole experience of

their cancer, but when they come to our clinic, we’re not getting to their problems.

If we find out that we can impact and improve communication between patients, don’t we want to bring

the results of our research back to our clinical care? Don’t we want to make a difference in our clinic

and change the way we treat, assess, and see our patient? We’re a practice discipline; it’s just not good

enough to only learn about these problems. What will it take to further promote appropriate clinician

responses when patients self-report these troublesome symptoms?

Well, we need some enhanced training; specialized training, communication training and notably for

psychosocial issues. For example, as a clinician are you comfortable listening to and responding to a

patient discuss the significant impact their cancer and treatment has on sexual activities and interest? If

you’re not ready to talk about that, find somebody who is, or have the brochure ready. If all you can do

is give the brochure, that is something and we haven’t ignored it and we haven’t changed the subject.

We need new research questions along these same lines. We’ve made a difference by giving the

clinicians a summary of the patient’s self reported symptoms, but now can our patients be prompted to

not only raise the issue with their clinicians, but then to go on and insist that someone deals with the

issue? Can we get our patients to engage in self-care issues by helping them understand their symptoms

in between clinic visits and monitor their symptoms and the effect of what they’re doing with self-care

on their symptoms? And finally can we improve symptom outcomes? These questions make up our next

clinical trial. This method I’ve described has been implemented at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance and

at Dana Farber where I am currently.

The bottom line of what this is all about: creating opportunities and an environment for individuals to

fully express themselves regarding their healthcare issues and then fully participate in their own

healthcare. We can do that by honoring their voice, by honoring their experiences; what they’ve been

through outside of the clinic and engage them in telling us their stories. We can harness technology to do

this that is efficient and cost-effective to reach every patient. My career in Seattle was profoundly

rewarding because I was able to address the issues and develop interventions that work for our patients.

It is that simple. Thank you to everyone who has been with me for these efforts!

2009

Taming the Dragon

Caring for the Patient with Advanced Cancer

Carla Jolley

2009 McCorkle Lecturer

When I first entertained the idea of using the dragon as a symbol of cancer, I was researching it from

the English historical perspective. In the years of early Christianity there was the need to slay the pagan

beasts. The saints such as St. George, slayed the enemy-“a dragon”, because it needed to be conquered

before it overwhelmed the hero and destroyed the villages.

When I apply this to our oncology patients, I think of the extensive symbolism that we use around the

“battle” with cancer. Patients see cancer as the enemy to overcome, and the foe like, the dragon in old

English times, to be fought and to be slayed. My thoughts then turn to the patient with advanced cancer,

for whom this mythical creature is typically depicted as gigantic and powerful, not unlike the diagnosis

of cancer. Their cancer or their “dragon” will ultimately lead to their demise and to the end of their life

journey.

So what if rather than slay the dragon, they learn to tame, to harness, to find another way to live with

this beast that has entered their lives and creates chaos and fear.

In fact, as I learned more about dragon lore I found that dragons are believed to have major spiritual

significance in many religions and cultures around the world. Not only are they depicted as gigantic and

powerful serpents or reptiles, but they have magical and spiritual qualities as well. Certainly they have

been portrayed as great foes of heroes, but also as great teachers of wisdom.

What can we do as oncology nurses to help patients reframe their relationship with their advanced

disease to assist them in the taming of the dragon so that they do not live in fear or are incapacitated by

their diagnosis? But instead, are able to feel empowered to make the most of their time left in their

journey, to find a way to maximize their quality of life, their interactions, and their relationships.

In summarizing of parts of my lecture, I will write about sustaining hope in patients with advanced

cancer. I will describe techniques I have found helpful, and those pearls of wisdom found in the literature

for establishing and clarifying goals of care then, lastly, transitioning patients for their final journey.

For those we care for or care about, those who have been diagnosed with advanced disease, Stage IV, or

with metastatic and/or recurrent disease it is not “If I will die of this disease….but WHEN. ” Hoping for

the best possible outcome, while preparing the patient for the worst outcome are not mutually exclusive

strategies. It is reasonable for patients and families to prepare for a range of outcomes. There is no harm

in dealing with advanced directives and preparing financial matters, even while hoping for a cure or for a

miracle. Addressing or raising these questions early on in the disease process makes it easier when

emotional states are less impacted by physical states. It does not make it however, less difficult for us

when dealing with our own discomfort about discussing difficult topics. Acknowledging that each

situation is unique and each person has individual coping styles and cultural implications, will guide us in

how best to approach these topics

Lived Experience

The lived experience of the patient with advanced cancer finds any resemblance of normalcy gone. They

often find themselves in a condition of crisis after the diagnosis. Normalcy can be replaced with

uncertainty and fear. Instead of “what are you doing” the questions becomes “how are you doing?” They

give away control of their well being to total strangers in hopes they will have the answers to questions

they don’t even know how to ask. It is a vulnerable time filled with selective hearing, stress induced

emotions in the middle of needing to make life-affecting decisions. Patients end up managing the outside

world of good intentions. I liken it to with what happens when a woman is pregnant: she is told all the

worst stories and more advice and suggestions than she could possibly have needed, much less wanted.

The internet has definitely magnified this by creating confusion, a lot of distrust, and many “what ifs?”

Part of good oncology care involves trust in the relationship with the health care providers; there is

actually a healing that can occur as a result of the relationship itself, a kind of ministry of presence. Then

also for the patient this lived experience with advanced cancer brings the loss of time. Time is everything

for the patient, caregivers, and loved ones. So much time ends up spent on the illness and not living to the

fullest, and so little time spent on joy- unless the patient is intentional. The other factors that often play

into the patient’s experience are lack of energy as well as the loss of control as the mighty dragon beast is

confronted.

One of the things to recognize as oncology nurses is that we just get a mere snapshot of the 24/7 of our

patient’s lives. Most patients really put their best face forward, as they often appear overly hopeful in

their relationships with their health care providers. I have seen patients in my practice who haven’t

dressed or been out of bed all week get “made” up for their clinic visit or treatment.

The picture on page one is of my Aunt Karen, and was taken a couple of weeks ago by a wonderful

caring oncology nurse. She had been diagnosed with breast cancer three years ago and was on a blinded

clinical trial for Arimidex vs. Tamoxifen and was having blood tests every 6 months and had increased

LFTs. I am guessing they were very elevated as they scheduled an ultrasound right away. She was

diagnosed with pancreatic cancer that had already metastasized to her liver….no symptoms. She would

say to me, “for a dying person I feel terrific.” Most of her symptoms these days are related to the

treatment side effects. She has been a caregiver to my uncle with fairly advanced Parkinson’s disease for

over 5 years (not what she had envisioned for her retirement about that time). It has been a very isolating

and limiting experience for her to be a fulltime caregiver. She has a strong faith and a supportive faith

community. I went with her to her first appointment; her oncologist laid it out for her very well in a

compassionate framework, was very clear this was not curative, and framed it that in the best of all

scenarios a good outcome, if all went well, would allow her a year.

But she had a very practical pressing need. Though she needs to hope for the best, now is the time to plan

for if things don’t turn out for the worst. She really needed to get her affairs in order and start planning

for my uncle’s care … now….not in crisis….avoidance and denial were a luxury. So unless we explore

what is important or pressing in our patient’s lives beyond the cancer experience we miss opportunities to

support them in meaningful ways.

Finding ways to stay positive and hopeful but still attend to the practical is a challenging balance. I think

oncology nurses have great opportunities and unique inroads with their patients to be able to help patients

and families find their own journey and to instill and sustain hope despite the inevitable.

Hope and Hopelessness

What is hope? It is an essential ingredient of the human existence. Hope maintains strength and gives

substance to courage and is about believing what is still possible. It is anything that contributes to a sense

of meaning and purpose. It is a trust in oneself and the future. It is a belief and an attitude that something

I desire or believe in can and/or will happen. It may be grounded in our spiritual beliefs, a belief that

something eternal exists, or that something sacred is around us and in us. Hope remains open to the

mystery that is around us. It remains open to all possibilities, including that things may turn out other than

imagined and it can still be okay. Hope becomes the anchor as we wait out the storm. Having cancer can

feel like a storm, a very significant storm.

Several studies have looked at characteristics of skilled clinicians who instilled hope through their

interactions with patients and they found that they included: honesty, forthrightness, confidence, good

listening skills, calm demeanor, good eye contact, compassion, and the ability to allay fears and anxiety.

These are characteristics that I see in many of my fellow oncology nurses and are attainable with practice

for those new into the field as well.

The well-known phrase, “while there is life there is hope” has far deeper meaning for our patients and it

is power in the reverse “while there is hope there is life…hope comes first and life follows”. Hope gives

power to life. Hope encourages life to continue, to grow, to reach out, to go on…despite living with a

serious illness.

I once had a patient who was told they had six months to live; he was one of those patients who continued

to choose treatment to fourth and fifth line drugs at great cost and significant side effects. As a former a