EDLP 704: Decision-Making: Legal Perspectives * Final Policy

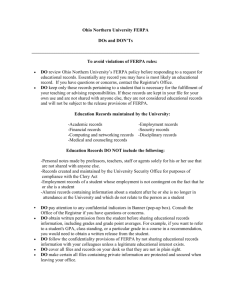

advertisement