Dissertation1

advertisement

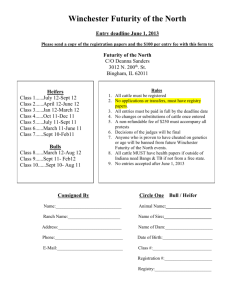

ARC3000: Dissertation A zooarchaeological analysis of the faunal assemblage from the Roman villa site of Yewden, Buckinghamshire. Student Number: 610005348 ABSTRACT! 610005348 Contents: 1. Introduction 2. Methods and Evaluation 2.1. Identification and Recording 2.2. Taxonomic abundances (NISP, MNE, MNI and MAU) 2.3. Age and Sex Identification 3. Results 3.1. Taxonomic abundances 3.2. Age and Sex 3.3. Surface Features 3.4. Butchery 3.4. Pathology 4. Discussion 4.1. Taxonomic Abundances 4.2. Age and Sex 4.3. Surface Features 4.5. Butchery 4.4. Pathology 5. Conclusion 6. Appendices 6.1: Appendix 1: Map of site location List of Tables: List of Figures: 2 610005348 1. Introduction: The animal remains examined in this work were excavated in 1912 by Alfred Cocks from the site known as the Yewden (or Hambledon) villa complex. The site is located south of the village of Hambledon, on the banks of the River Thames (Appendix 1), and was ideally situated for links to Dorchester, Verulamium (St Albans) and Silchester (Eyers and Mays 2011, 28). It is joined by another smaller villa about half a kilometre away at Mill End, which is as yet unexcavated but has been identified through survey (Eyers and Hutt 2012, 75-82). It is likely that the villas were connected through ownership and, although it is unclear what the relationship was between them, it is assumed that the Mill End villa was a secondary villa with a different function to the Yewden complex. The Yewden villa was established in the early 1st century AD and occupation continued through to at least the end of the fourth century (Cocks 1921, 141) - It should therefore be noted that the animal remains recovered represent a palimpsest, accumulated over this whole period, and interpretation should take this into consideration. The complex briefly comprises an enclosure wall, surrounding a principal dwelling-house accompanied by two other dwelling structures and a fourth “Little House”, potentially a shrine (Cocks 1921, 141-4). A total of fourteen furnaces and associated flues were also identified, interpreted by Gowland (1921, 158) as having been used for grain drying due to the discovery of barley and wheat specimens, as well as a lack evidence for very high temperatures or iron-working slag (Appendix...). Perhaps the most noteworthy feature of the site was the discovery of 97 peri-natal infant burials (Mays et al. 2011, 1), leading to the controversial interpretation of the villa as a potential brothel due to the similarity to other sites such as Roman Ashkelon, Israel (Mays and Eyers 2011, 1931). However, this conclusion is seen as controversial, and some believe that further analysis of evidence should be undertaken before it is accepted. In light of these findings, the animal remains were given negligible attention by both Cocks and later works, which solely focussed on the human remains. Hence, the aim of this work was to interpret the site objectively using zooarchaeological remains to shed light on the economy operating there. 2. Methods and Evaluation: 2.1. Identification and Recording: The recording of the 45 boxes, amounting to 2860 specimens, was facilitated by the use of a database. Where identifiable, the following information was recorded for each specimen: location, based on Cock’s labelling on the specimens, species, element, zone (i.e. proximal, distal, shaft, fragment), fusion (i.e. fused or unfused, and which end if bone with multiple epiphyses), and side (i.e. left or right). The bones were also examine for evidence of butchery or pathology – butchery marks were identified as either cut, chop, or saw marks, and their position on the specimen was recorded. Any breaks in the specimen were categorised as either fresh or dry fracture. Another factor to be considered was the presence of surface features, documented as acid etching, gnawing, root etching, and any abnormal colouration of the bone, including charring. Lastly, the recording of age or sex indicators was also included in the database, for example estimates of age based on bone size or formation, and mandible wear stages. Photographs were taken of specimens with notable features, and the reference number for this image included in the table. 3 610005348 Identification of species and element was undertaken using personal notes and books, for example Cohen and Serjeantson (1986, 10-97) for the classification of birds. Reference collections at Exeter University were also valuable, as well as personal communications with Professor Alan Outram. A number of challenges were faced in the analysis of the assemblage, particularly my distance from assemblage, restricting time available to analyse it, and lack of a reference collection whilst examining the bones at the Buckinghamshire County Museum Resource Centre in Halton, Buckinghamshire. Furthermore, the previous context recording system used by Alfred Cocks in 1912 in the form of stickers attached to bones was often unclear, missing, and at times inconsistent. 2.2. Taxonomic Abundances (NISP, MNI, MNE and MAU): The first taxonomic abundance to be recorded was the NISP (Appendix...) for each species, meaning a count of the number of specimens identified per taxon (Lyman 1994, 100). The NISPs of each species in locations across the site were also tabulated to assess species distribution across the site (Appendix...). However only specimens that could be assigned to context were included - many were in boxes which, although labelled, did not indicate find location. While NISP values are easy to derive, they do not account for interspecies variation in element number, causing some species to be over/under-represented, and are also affected by varying fragmentation (Klein and Cruz-Uribe 1984, 25; O’Connor 2012, 55-6). To account for fragmentation the MNE was derived from the NISP values – specimens were only counted as being from different elements if they differed in zones, fusion states, surface features or side (Chaplin 1971, 70) (Appendix...). However, only specimens assignable to a species and side could be included in this analysis, meaning that some bias may have been introduced into the results at this point. To account for variation in element number between species the MNI was obtained from the MNE data. This is the smallest number of individuals to account for the recovered skeletal elements for a species (Shotwell 1955, 330-1; Watson 1979, 127). It is calculated by dividing non-paired elements by the number found in the skeleton to eliminate inter-taxonomic variation, and identifying the most frequent side of the most abundant skeletal element (O’Connor 2012, 59). Decimal values were rounded down for this purpose. This gives some indication of the number of animals present on a site, however, Reitz and Wing (2008, 206) maintain that it should not be taken as an exact number. 2.3. Age and Sex Identification: With regards to age, mortality profiles, especially caprid, are very important in determining economy, as they take into account the mortality patterns across the assemblage, and not just of individuals (Zeder 2002, 87). Therefore, mortality profiles for both caprids and cattle were constructed for the Yewden assemblage using the following methods. Firstly epiphyseal fusion was considered for cattle and caprids. The assemblage contained no whole skeletons, so differing ages at which bones fuse were categorized into stages based on known fusion ages (Silver 1969, 252-3), allowing for the assessment of age distribution on the site as a whole rather than for individuals. Both the cattle and caprid stages cover the fusion of epiphyses in around the first 4 years of life, meaning that an adult individual cannot be accurately aged (Zeder 2002, 89), and the broad age range in each 4 610005348 stage reduces the accuracy of ageing younger animals (Grant 1975, 395). Nonetheless, the percentage survival at each stage was calculated using by comparing the number of fused ends to the total MNE (Table...AND...). Furthermore, it could be argued that epiphyseal fusion may be affected by the differential preservation of fusion points (Maltby 1981, 171) – therefore ageing using tooth eruption and wear was also considered to provide a more comprehensive age distribution. While there were not enough cattle mandibles to successfully utilise tooth ageing as outlined by Grant (1982, 91-105), the caprid specimens were assessed using this method. This was achieved by following Payne’s (1973...) method of categorising mandibles into one of eight wear stages, based on eruption and wear (Zeder 2002, 95). This method may have some limitations, for example: it provides a relative sequence rather than an absolute age indication (Maltby 1981, 171); it is only useful until the last tooth in the sequence comes into wear; and it does not account for differences in individual animals and breed (Chaplin 1971, 78). However, it is considered more reliable than fusion as teeth are more often preserved (Reitz and Wing 2008, 195). The highest age in the wear stage, in years, was plotted against the percentage of mandibles exhibiting that wear pattern, and a percentage survival curve was also plotted on the same axis, in which a cumulative percentage reduction indicates the proportion of animals surviving to the next wear stage (Figure...). Sex?: o NOT METRIC; not enough evidence? Some observable traits include – cattle horns/ pig canine/ one example of a horse pelvis which could be assigned to a sex (Chaplin 1971, 100). 3. Results: 3.1. Taxonomic Abundances: o Compare basic frequencies (NISP) to Cock’s results; BUT, doesn’t take into account number of elements in skeleton of each species, or the same fragmented elements from the same individual. Therefore... o MNE: lower, as non-overlapping fragments may have come from the same element and are therefore treated as such (ref.). Also, elements that could not be assigned to a side were not included in the count, thus lowering the results (BIAS???!). o MNI: Considerably lower, and showing a slightly different prevalence of species? o DISTRIBUTION PATTERN IN SPECIES? TABLE IN APPENDIX! – locations with most finds represent deposition of whole animals? (e.g. pit 15 and the well are dominated by pig bones, pit 21 contains a near-complete hare skeleton, pit 1 mainly comprises dog) 3.2. Age and Sex: o Caprid Mandibles: Stage E (2-3 years) is the most frequent mandible wear stage, comprising almost 30% of the sample, however peaks are also present at stages D 5 610005348 o o (1-2 years) and G (4-6 years), representing 15% and 19% of the sample respectively. This double peak in age distribution suggests higher mortality in caprids between 1-3 years, and 4-6 years. Furthermore, the percentage survival curve shows a relatively high rate of survival until around 2 years, when survival drops from 70% to 40%. After this point survival drops in a relatively consistent pattern, at a rate of approximately 10% per year, until it reaches 0% at 10 years. Caprid epiphyseal fusion: GRAPHS??? Limited success? See cattle below... Unfused bones often under-represented, especially in the first year, as they are more susceptible to taphonomic factors (Grant 1975, 395) – BUT can this go as far as explaining the overall lack of unfused elements? Table...: Caprid percentage survival based on epiphyseal fusion. Source: author Stage MNE unfused fused % survival 1 (6-10 months) 3 0 3 100.00 2 (13-16 months) 3 0 3 100.00 3 (18-28 months) 71 15 56 78.87 4 (30-42 months) 12 3 9 75.00 o Cattle epiphyseal fusion: limited success, as fusion stages only age the animal up to around 4 years (Silver 1969, 250)...ALSO over-representation of some elements (e.g. 1st phalanges) causes problems??? – no infant mortality??? Table...: Cattle percentage survival based on epiphyseal fusion. Source: author Stage MNE 1 (7-10 months) 2 (12-18 months) 3 (24 -36 months) 4 (36-48 months) o unfused 19 408 53 78 fused 0 2 1 2 19 406 52 76 % survival 100.00 99.51 98.11 97.44 Sex?: o not enough evidence? Some examples – cattle horns/ pig canines (?)/ one example of a horse pelvis which could be assigned to a sex 6 610005348 COMPARE TO PAYNE (1973)!!! Figure...: Caprid percentage survival at each of Payne’s (1973) wear stages, and the distribution of ages, based on tooth eruption and wear. Source: author. 3.3. Surface Features: o Gnawing: (Shipman and Rose 1983?) Dog Gnawing can be identified in an assemblage by the presence of the following features: round, blunt impressions caused by the canines; U-shaped furrows with very small crushing marks at the bottom; splintering of long bone shafts; or by the complete gnawing away of joints resulting in an uneven surface and a shaft with ragged ends (Noe-Nygaard 1989, 488-9; Reitz and Wing 2008, 135). In the Yewden assemblage there are 43 examples of gnawing, with the latter characteristic especially evident (Figure...) – this supports Haynes’ (1983, 165) assertion that gnawing marks are often found near the epiphyses as a result of chewing using cheek teeth. The elements showing gnawing are mainly those of the leg - astragalus, calcaneum, femur, humerus, metapodial, and first phalanges – however there are also some examples on mandibles (Figure...). The most frequently gnawed bone is the calcaneum, with 14 examples... (Haynes 1980...). There is less variation in species, with only specimens from caprid, cattle and horse displaying signs of gnawing, totalling 2, 27, and 14 examples respectively. Another surface alteration present in the assemblage was charring – often characterised by a colour change, to black or brown initially, then blue-grey or white (Lyman 1994, 385). An increased brittleness was also indicative of burnt bone, as well as a size decrease of up to 5% (Reitz and Wing 2008, 130-2). There are a number of factors which will have affected the extent of charring, for example the intensity of heat, duration on exposure, proximity to fire, and size or shape of the element (Bennett 1999, 2-5). However, the alterations evident on all 24 examples in the Yewden assemblage are relatively consistent, all being black (Figure...). The charred specimens again show a high frequency of cattle bone alteration, with 17 examples. There are a further 4 charred caprid bones, and single examples of red deer, horse and pig. However, the pattern in affected elements is less 7 610005348 clear, as charring is found on a variety of elements with metatarsals being the most frequently modified (Figure...). Frequency Frequency of Charring on Different Elements 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Element Figure...: Frequency of different elements affected by charring. Source: author. o There is also a single example of acid etching in the assemblage - a whole cattle metatarsal (Figure...), with the distal end of the shaft affected. Root Etching is also evident on 9 specimens, varying in species: 3 caprid, 3 cattle, and single examples of horse, red deer and dog. The elements affected also vary, comprising 3 mandibles, 2 metatarsals, 2 metacarpals, a femur and a radius. : plant roots leave “characteristic dendritic patterns”, evident as lightly etched grooves (Reitz and Wing 2008, 139). This resulted in the appearance of “dendritic patterns” of shallow grooves, caused by the excretion of humic acid by plant roots (Lyman 1994, 375-6) ... o Fracture Features – taphonomy?? Taphonomy/ preservation level? Relative completeness? (Shotwell 1955, 331 – NISP/MNI = number of specimens per individual) REITZ AND WING 2008 – 141: FRAGMENTATION (FRESH/DRY) Victorian vandalism! – A final surface feature which deserves a brief mention is the alteration of specimens during the Victorian period for their use in museum display. For example, ... 3.5. Butchery: There are 94 specimens within the Yewden assemblage showing signs of butchery – these consist of three types: cut marks, chop marks and saw marks (Figure...). Cut marks were identified as small V-shaped incisions, often with fine striations parallel to the direction of cutting and occurring in parallel clusters (Shipman 1981, 365; Reitz and Wing 2008, 128). These were the most common type of butchery marks present in the assemblage, evident on 38 examples. They were most prolific in cattle (31 examples), especially on the lower leg bones such as metatarsals and first phalanges (Figure...GRAPH!). However, cut marks were also found in varying locations on 3 caprid specimens, 1 horse bone, and 3 red deer 8 610005348 examples (Table...?) (Table...? – NEED TABLES FOR OTHER SPECIES?). Chop marks consisted of a deep, non-symmetrical “V”-shaped features tilted in the direction as the chop action, lacking striations (Figure...) (Noe-Nygaard 1989, 473). This type of mark was found on 37 specimens, and were again most common in cattle leg elements (numbering 28), followed by 3 red deer specimens, 2 caprid and horse specimens, and one example on both pig and fowl. Saw marks were the least common type of butchery present in the assemblage, with only 19 examples (Figure...). These were characterised by bone and antler cut at a right angle to the shaft of the specimen, leaving a flat cross section with serrations crossing each other at acute angles (Reitz and Wing 2008, 130; Noe-Nygaard 1989, 473). Most noticeably 84% of saw marks were found on the antlers of red deer (16 examples) (Figure...GRAPH!), with two bovine specimens and one roe deer antler specimen constituting the remaining examples. It is likely that these marks are a result of butchery, rather than taphonomic factors like...., as...(Shipman and Rose 1983, 63?; Shipman 1981) o o EXAMPLES! – PICTURES!!! Butchery SEQUENCE?? (Shipman and Rose 1983, 75 – relevant, as hominids?) Table...: Type and frequency of butchery marks found in the Yewden assemblage. Source: author. Cut marks Chop marks Sawn caprid cattle fowl (Galliforme) horse pig red deer roe deer 3 31 3 2 28 1 2 1 3 Total 38 37 1 2 16 1 19 9 610005348 Frequency of Butchery Mark (%) Distribution and Frequency of Butchery Marks on Cattle 25.00 20.00 15.00 10.00 Cut 5.00 Chop 0.00 Saw Element Figure...: Chart showing the proportion of different butchery marks found on different cattle elements .Source: author. Figure...: Diagram showing the positions and frequency of cattle butchery marks. Source: author. 10 610005348 3.4. Pathology: Within the assemblage there are sixteen examples of pathology, all relating to either horse, cattle, dog or large mammal. Two horse specimens showed pathological changes. A second phalanx (Fig....) exhibits exostosis, which is the formation of new abnormal osseous tissue on the outside of a bone (Baker and Brothwell 1980, 225), along the entire length of the bone. It is especially distinguishable at the proximal end, while the articular surface of distal end is not affected. A first phalanx also displays exostosis, although it only affects the shaft of the bone and is less severe (Fig...). Figure...: Horse second phalanx displaying exostosis, especially at the proximal end of the bone, with the distal articular end unaffected. Source: author. Figure...: Horse first phalanx showing slight exostosis along the shaft. Source: author. 11 610005348 There are also three examples of cow phalanges displaying abnormal osseous growth. Two exhibit ossification just below the articular surfaces of both proximal and distal joints (Figure...), while the last shows ossification along the shaft, becoming more severe at the distal end (Figure...). Other bovine lower leg bones are also affected, for example a calcaneum also exhibits exostosis around the distal articular surface (Figure...). Another cattle calcaneum shows signs pathological change in the form of ossification and a relatively drastic deformation of shape, particularly at the distal end – potentially evidence for a healed injury. Further bovine lower leg pathology occurs on a metacarpal (Figure...), which shows osseous growth specifically at the distal end, with the carpals fused at the joint but apparently intact articular surfaces. The only bovine pathology not affecting a leg is found on a right cow mandible, which has bony outgrowth towards the proximal end (Figure...). The final example of pathological changes to a bovine specimen is a tibia displaying enormous amounts of abnormal bone growth along an abnormally-shaped shaft (Figure...), potentially the result of another healed injury. Figure ...: Cow first phalanx with exostosis below the proximal and distal articular surfaces. Source: author. 12 610005348 Figure...: Cow first phalanx showing exostosis along the shaft and distal end of the bone. Source: author. Figure...: Cattle calcaneum showing evidence for exostosis around the distal articular surface. Source: author. Figure...: Bovine calcaneum with osseous growth and abnormal shape, potentially as a result of healed injury. Source: author. Figure...: Cattle metacarpal with severe exostosis at the distal end, resulting in ankylosis of the distal surface and carpals. Source: author. 13 610005348 Figure...: Cattle mandible with bony outgrowth towards the proximal end. Source: author. Figure...: Cattle tibia with huge amounts of osseous growth, potentially resulting from a badly healed injury. Source: author. There are five large mammal vertebrae which also display abnormal osseous growth, although all specimens are vertebrae. The destruction of cartilage between the vertebrae has led to fusion of the vertebral bodies, shown in the ring of bone growth around the edge of the centrum (Figure ...). Lastly, two dog specimens show pathological change. A metacarpal shows signs of exostosis at the proximal end (Figure...), resulting in destruction of the proximal articulation. Also, a right canine radius exhibits exostosis along the shaft, indicative of a healed fracture (Figure...). Figure...: One of the five large mammal vertebrae, in which cartilage destruction has led to the fusion of the vertebral bodies resulting in osseous growth around its rim. Source: author. 14 610005348 Figure...: The proximal end of the dog metacarpal affected by exostosis. Source: author. Figure...: Right canine radius showing exostosis along the shaft, probably due to a healed fracture. Source: author. 4. Discussion: 4.1 Taxonomic Abundances: o species represented/ frequencies (MNI, MAU) – economy? 15 610005348 o o o o Why does MNI so drastically reduce, especially in cattle?? Different fragmentation patterns (Klein and Cruz-Uribe 1984, 26) – cattle more fragmentary/ more bones such as phalanges? What exploited from each animal? General Roman pattern: o Grant (2003, 373) states that there is no general Romano-British pattern for the meat exploited or husbandry practice employed as there is substantial variation in species proportions and age distributions – she suggests that the pattern of animal exploitation on any given site depends upon a combination of local environment, traditions, trade and distribution, social and economic status, food preferences, and population migration. o However, King (1989, 53) points to the general prevalence of domesticates like sheep, cattle and pigs on Romano-British sites. : IS THIS THE CASE AT YEWDEN?? o There is also an argument for a progressive decrease in sheep relative to cattle and pig during the Roman occupation of Britain, described as the “Romanisation” of diet by Hamshaw-Thomas (2000, 166-7). Grant (2003, 373) suggests that the rapidity of this change from the previous Iron Age pattern depended upon the proximity of the site to developing towns or roads. o The distinction between villas and “un-Romanised” sites suggests that the occupants of villas adopted a Romanised approach to diet and therefore agriculture (King 1989, 54). o (Yewden has a lot of cattle, but also a lot of caprid and relatively few pigs – transition??); Is this similar to Barnsley Park, also in the Thames Valley, where sheep are dominant in the assemblage throughout the Roman period. King (1989, 58) describes the site as “semi-Romanised”, although it may just be that the area was more suitable for grazing caprids – lowland areas with dry, light soils (Maltby 1981, 163). o Explanation? It has been suggested that this transition in Roman diet, evident in zooarchaeological evidence, was the result of a population increase in 4th century which necessitated the exploitation of marginal areas more suited to cattle or pig husbandry, or that economic decline towards the end of the Romano-British occupation led to the introduction of capitatio, or poll tax meaning that livestock with more meat per head was preferred (Davis 1987, 183). Furthermore, increased demand from non-food producing areas such as military settlements and towns may have called for exploitation of animals which would provide more meat per individual (Grant 2003, 373). Cattle were certainly the most important species to the roman urban and pastoral economy (Vann 2008, 36; Dobney 2001, 36; Maltby 1989, 89), perhaps explaining their prevalence in the Yewden assemblage – although the higher number of caprids in terms of MNI may suggest a different pattern in countryside villas. (BUT LARGER ANIMALS SO LESS NEEDED??) o Increase in cattle also relates to large-scale adoption of cereal production therefore necessitating the use of draught animals (Grant 2003, 377); o Cattle kept mainly for traction and sometimes for milk (Davis 1987, 183); “broad multi-purpose use” for meat, milk and traction (Dobney 2001, 36). o Although, Grant (2003, 372; 1971, 377-88 – Fishbourne) suggests that many were killed before reaching maturity. 16 610005348 “Head and feet”?? (Gidney 2000, 170): horn cores, frontal, lower jaw, and metapodial fragments in archaeological record from Causeway Lane, Leicester, suggest (industrial) horn working and/or tanning, in which the horns and feet were probably attached to the hides and later removed for use. o Another site situated close to the Thames and displaying a high frequency of cattle specimens is Barton Court – King (1989, 56) suggests that this type of location was ideal for raising cattle as it enabled the integration of the site into a regional market. Therefore, the animals raised at Yewden may have provided not only provisions for the site, but tradable goods distributed via the Thames. Caprids: o Probably sheep! British climate more favourable for them (Grant 1975, 397) o kept mainly for wool (Maltby 1981, 171), and secondarily for milk and meat (Davis 1987, 183; Grant 1975, 396) o Tend to be killed at older age in villa sites – increased importance on wool production? (Grant 2003, 372). Pigs: most regularly eaten in Roman diet (Davis 1987, 183); classical sources suggest that pig meat was highly valued in Roman diet, however a prevalence of pig is not evident in the zooarchaeological record at Yewden or indeed across Northern Europe (Dobney 2001, 36) Grant (2003, 372) supports this, stating that at Fishbourne villa, Sussex, there is a 2nd to 3rd century decline in the prevalence of porcine bones in deposits. Noddle (1984, 111) states that there is no overall trend in Romano-British pig exploitation, and therefore that the species did not play a major role in diet. Dogs: Large amount of Roman evidence (Harcourt 1974, 164); used for herding or hunting - even small ones (Groot 2008, 49). BUT: variation in size and build = emergence of “lap-dog” – sheltered, would not have survived as a scavenger? (Harcourt 1974, 164); larger dogs used for hunting/ guarding/ fighting (Harcourt 1974, 168); Fowl/Geese: Chickens first appear in the archaeological record in Britain in the Late Iron Age, but they increase in importance in the Roman period; their remains, together with those of geese and ducks, are common in Romano- British towns. (Grant 2003, 377). Deer (both red and roe) over-represented due to large number of antlers, and a relatively small frequency of other elements? – suggests that deer were NOT being used to supplement the diet provided by domestic stock?? This may be due to the fact that antlers are shed subsequent to the annual rut (Alhaique and Cerilli 2003, 103), increasing the ease of procurement as the animal does not necessarily have to be hunted and killed to obtain these elements. Grant (2003, 374) claims that deer, including large red deer, played little part in the Roman diet – instead it is possible that, while the meat from these animals was not exploited, products like antlers may have been used for other purposes such as tool-making or ornamentation (Reitz and Wing 2008, 130). The presence of mainly shed antler in the assemblage, as well as a lack of a comparable amount of other red deer elements suggests that antlers were mainly collected, having been shed after the rut, for use in craft production – Alhaique and Cerilli (2003, 104) suggest that they were used by Romans to make items such as buttons, combs, decorative clasps, needles and awls, and hafts for implements and weapons. Grant (1981, 210) maintains that antler was more suitable then bone for such functions as it is denser, and therefore stronger, than bone. DISTRIBUTION! – locations with most finds represent deposition of whole animals? (e.g. pit 15 and the well are dominated by pig bones, pit 21 contains a near-complete hare o o o o o o o 17 610005348 skeleton, pit 1 mainly comprises dog) Other species are spread throughout the structures, as well as in pits all over the complex – no specialised areas of “industry”?? 4.2. Age and Sex: NOT ENOUGH EVIDENCE FOR SEX DISTRIBUTION?! Some elements provide unambiguous indication of sex, such as pig canines, cervid antlers, cattle horns or pelvic bones of equines and cattle (Greenfield 2002, 68-9; Grigson 1982, 10). However, there were not enough distinguishable examples in the Yewden assemblage to provide a comprehensive sex distribution for the site – for example, only one example of a definite male pig mandible was identified, as well as a single male horse pelvic section. Grant (2003, 379): maintains that rural animal bone assemblages tend to comprise animals killed at a variety of ages, indicating the use of both primary and secondary products. It is also postulated by Grant (2003, 379) that villa sites display variation in age distribution as animals are raised to meet primarily the demands of the villa owner, with the potential for trade for other items. Falkner (2000: 150–1) has inferred the existence of two economic systems – the estate owners producing for a market, and the native farmers with a more self- sufficient husbandry. Cattle: o Seems to be an unusual predominance of very elderly cattle, based on the epiphyseal fusion data (Table...). BUT: is this reliable? over-representation of some elements/ loss of unfused elements due to taphonomic reasons? OLD CATTLE SUPPORTED BY EXAMPLES SUCH AS WORN MANDIBLE?!!! (Figure...) o o o o o “The age and sex distribution of the slaughtered cattle can be used as complementary evidence for the exploitation of animal power. A dominance of animals killed at a young and sub-adult/adult age points to their importance as meat suppliers while cattle kept until older age may indicate that dairy products or physical power were important. In the latter case, the occurrence of castrated animals can indicate the keeping of draught-purpose cattle.” (De Cupere et al. 2000, 256) Meat: best if animals killed around 4-5 years (Noddle 1984, 111); Milk: lots of elderly individuals in assemblage, as well as a relatively large amount of young individuals being killed, representing the male calves surplus to breeding requirements (Dobney 2001, 37) Roman pattern, based on mandibular tooth eruption and wear (Maltby 1981, 179-82) = mainly older individuals, but a range of ages are represented. ALTHOUGH: Barton Court Farm; Shakenoak Farm, Oxfordshire; Fishbourne – relatively immature cattle present (killed for meat, OR not needed for breeding, working or dairying so killed for meat/hides). Expensive to rear animals solely for meat – animals kept to an older age as they could then also provide labour, young, and dairy produce (Noddle 1984, 111)?? Portchester Castle (GRANT 1975, 398-404): tooth eruption and wear – mainly older individuals (over 5 years old) – unlikely that they were solely raised for meat (Maltby 1981, 182), as cattle were allowed to reach maturity. This suggests that cattle working and dairying were more important within the economy. Grant (1975, 396) suggests that cattle used for traction would be fairly old before they were killed, in order to receive return for the effort of 18 610005348 o training them. – frequency of butchery cuts suggests that animals were eaten in the end (Grant 1975, 404) However, younger cattle also present as a site such as Yewden may have been self-sufficient, meaning that some younger animals would have been exploited for multiple resources (i.e. some also killed for meat) ??? Caprids: EPIPHYSEAL FUSION SUPPORTED BY MANDIBLE AGEING??? o Wool production: mainly ewes and castrated rams allowed to reach maturity (Noddle 1984, 115) (RELEVANT?) – allows for the collection of several annual growths of the fleece (Malbty 1981, 171). o Meat production?: predominance of younger animals in the assemblage (Malbty 1981, 171). o Older age distribution on rural sites? (Grant 2003, 377) - points towards animals being kept for non-meat products like wool, horn and hide (CATTLE TOO) – may also have been used for milk (Dobney 2001, 37) o The contribution of sheep to the urban food supply was small when compared to that of cattle, but still significant. Sheep played another crucial role in the rural economy: wool production was well established in Britain long before the Roman Conquest, but it became increasingly important in the following centuries. In bone assemblages in the third or fourth centuries at a wide range of towns and smaller settlements, there is an increase in the remains of mature sheep, animals that would have proved several clips of wool before being sold off for meat (for example, O'Connor 1986; Levitan 1989; Dobney and Jaques 1996; Dobney et al. 1997; Grant 2000) – SITE EXAMPLES!!!. (Grant 2003, 380). o HOWEVER!!! Portchester Castle (Grant 1975, 396): evaluated using a numerical system of ageing mandibular cheek teeth; most animals were killed at a value corresponding to Payne’s stages D and E (Maltby 1981). This corresponds to the pattern at Yewden, and suggests that animals were killed for meat at around 2-3 years (Maltby 1981, 175). o Overall – sheep killed for meat around 2-3 years? BUT the survival of older animals also suggests a mixed economy, in which wool was also an important resource. This is supported by Payne (1973...), who suggests that sites rarely operate a single economy. 4.3. Surface Features: Clearly the incidence of dog gnawing suggests the presence of dogs at the site during the period when elements of other species were being discarded – this is supported by the presence of canine specimens in the assemblage. However, it could also give an indication of speed of deposition, as less gnawing could imply a more rapid deposition after discard (Maltby 1984, 128; Stallibrass 2000, 159). Therefore it follows that in the Yewden assemblage elements such as astragali, calcanea, femurs, humeri, metapodials, and first phalanges may have been left out longer before accumulation into the archaeological record, as they exhibit a greater degree of chewing. The pattern of gnawing somewhat follows Davis’ (1987, 26) assertion that long bones are most frequently affected, however he also states that small bones under 2.5cm diameter are swallowed whole, meaning that acid 19 610005348 etching, which leaves a characteristic smooth surface, should also be considered when analysing scavenging activity. It should also be noted that dog can remove meat without leaving marks (Kent 1993, 339), therefore gnawing may not be fully represented in the archaeological assemblage. As for species, Stallibrass (2000, 159) encounters more gnawing on caprid and pig bones than cattle, and proposes that this is due to the fact that larger bones, from cattle for example, are often removed prior to cooking and deposited, whereas smaller bones of sheep and pig were often cooked with the meat still on them and then given to dogs when the food was eaten. This processing decision may also be shown in butchery patterns, which are discussed below. Although some examples of gnawing on caprid bones are evident, the fact that cattle bones were most frequently gnawed in the Yewden assemblage suggests that dogs had most access to these elements. This may be due to a delay in deposition of bones of this species, allowing time for them to be chewed. Haynes (1980, 346) suggests that joints disarticulated early in the butchering sequence may show more signs of gnawing. If this is the case, it could be suggested that the leg bones, especially of cattle, were removed early on during processing therefore leaving the epiphyses exposed to the gnawing that is evident in the assemblage. There are a number of explanations possible for the charring in the assemblage. For example, Dobney (2001, 40) suggests that bones were often heated in order to make them more brittle and therefore easier to break for marrow extraction. However, the lack of evidence for the breaking of bones for this purpose at Yewden necessitates the search for a more likely explanation for charring. Reitz and Wing (2008, 131) suggest that cooked meat is usually boiled, baked or roasted – they state that whilst roasting meat parts of bone, especially joints, covered by the least flesh are exposed to the flame and therefore burn. It is therefore likely that the charred specimens in the Yewden assemblage were the result of roasting meat for consumption. However, Lyman (1994, 384) states that this view is simplistic, as charring can also result from accidental cause, such as the burning of a structure containing bone, or the use of bone as fuel (Théry-Parisot 2002, 1415). The black colouration of the burnt elements is suggestive of heating under a relatively low temperature, as the organic components are carbonized (Bennett 1999, 2). This suggests that the Yewden examples were exposed to relatively low heats, perhaps just deliberate domestic fires required for cooking. The prevalence of charred cattle elements is suggestive of that species being chosen most often for cooking – this may also be present in butchery patterns. Cattle AND Metatarsals most often affected – why?? – ROMAN DIET BOOKS? Acid Etching?? – complete cattle metatarsal – how?? o Root etching – examples in varied locations, suggesting it did not just occur in one area of the site? Suggests that the specimens were deposited in a “plantsupporting sedimentary environment” and experienced little disturbance (Lyman 1994, 376). Dry/ Fresh fracture – taphonomy?? Taphonomy/ preservation level? Relative completeness? (Shotwell 1955, 331 – NISP/MNI = number of specimens per individual) 4.4. Butchery: 20 610005348 Consideration of butchery patterns can indicate not only the types of tools used at the Romano-British villa, but also the elements chosen for butchery and therefore the diet and economy of the site. Cut marks were the most common alteration found in the assemblage, and are suggestive of the use of knives in removing meat - (Noe-Nygaard 1989, 471) argues that these marks are often a result of skinning, disarticulating the carcass, or removing meat prior to cooking. Also prevalent were chop marks, which Reitz and Wing (2008, 127-8) state are probably the result of the use of a large instrument like a cleaver, hatchet or axe to dismember a carcass, and that they are often located around large joints and sometimes along bone shafts. Butchery marks were most common on cattle bones, suggesting that this were the primary species being utilised for meat on the site. As mentioned above, it is likely that the bones of larger animals were removed before cooking, rather than roasting the meat on the bone (Stallibrass 2000, 159) – this could explain why butchery marks were predominantly found on cattle bones, as it is likely that the carcass was dismembered and portioned before cooking. The fact that both cut and chop marks were most common on bovine leg bones suggests that limbs were being removed? (...),Maltby (1989, 75): “major meat-bearing limb bones of cattle” = humerus, radius, femur, and tibia – potentially why legs were being removed, as they contained the most meat? Subsequent butchery to remove the large amounts on these bones may be represented by the marks on the leg bones, especially at joints. Dobney (2001, 40) Cattle butchery involved “chopping off all major elements” – including legs? Although the splitting of long bones he also purports to be typical Roman practice is not evident at Yewden. Mandible chop mark – associated with detaching mandible from skull, probably using a cleaver; seen in examples from Roman Winchester and Silchester (Maltby 1989, 78) A typical Roman butchery practice described by Stallibrass (2000, 160) is the defleshing of the scapulae to gain access to the large muscle mass on the bone – a cleaver was used to trim around the articulation, in order to disarticulate the scapula from the humerus (Maltby 1989, 79), then the meat was removed from the flat section of bone (Grant 1975, 392). This type of butchery could account for the presence of both cut and chop marks around the cattle scapulae, as well as an occurrence of cut marks on the centre of the blade. This distribution of butchery marks could provide evidence for the development of new butchery practices, documented by Dobney (2001, 41), in which shoulders of beef were preserved by smoking or salting (Maltby 1989, 81) – Grant (2003, 377) suggests that this could be another result of increasing Romano-British population towards the second century AD as meat then needed to be storable. HUMERUS: (Maltby 1989, 81): disarticulation from the radius/ulna, as all found at distal end. FEMUR: (Maltby 1989, 81-4): Cut marks on long bone shafts = filleting? (Grant 1975, 392) CALCANEUM: butchery marks associated with removing the extremities from the tibia (Malttby 1989, 86). 21 610005348 METAPODIALS (Maltby 1989, 86-8): usually less marks than upper limb bones – NOT the case here! fewer marks from filleting, as less meat on these bones? Associated with bone working? OR disarticulation of metapodial from upper limb (Grant 1975, 392) 1ST PHALANX: (Maltby 1989, 88): more cut marks than chop marks – “common practice to make incisions around the toes to enable the skins to be removed”. The chop marks could again represent disarticulation from the metapodials above. BUT – butchery marks are accidental! Other animals may have been used for meat, but the butchery may not show in the archaeological record (Lyman 1994, 297). Furthermore, evidence for the butchery of smaller species like caprids and pigs may not be present as, while cattle bones were removed through butchery prior to cooking, smaller bones may have been cooked with the meat still on them (Stallibrass 2000, 159). Deer antlers: mostly sawn – used for making tools/ornaments, as mentioned above? (Alhaique and Cerilli 2003, ...); While dogs are relatively common on the site, there are no specimens showing signs of butchery. This suggests that dogs were deposited as whole corpses (Stallibrass 2000, 160), although sufficient contextual information is not available for determining whether they were found as whole skeletons. Grant (2003, 381) states that, while dogs were eaten in pre-Roman times, the decrease in butchery marks on the bones of these animals during the Romano-British period implies that a change in diet meant that they were no longer consumed. Overall Maltby (1989, 89) states that there is no universal Roman butchery pattern, especially in rural areas were greater variation occurred. However at Yewden it seems that, based on butchery marks, the main species exploited was cattle, with the use of meat from the shoulder and limbs. 4.5. Pathology: All of the pathologies in the Yewden assemblage were manifested as exostosis, i.e. abnormal bone growth. Vann (2008, 32) claims that, while bone growth often indicating inflammation or infection is common on Roman sites, it is difficult to identify specific causes of bone growth - however an attempt has been made to identify cause where possible. The arthropathies present on the first and second horse phalanges may be the result of osteoarthritis (OA), which is the most common type of joint pathology (Jurmain and Kilgore 1995, 443). However, Baker and Brothwell (1980, 115) state that in order to positively identify OA at least three of the following characteristics must be present: grooving on the articular surface of the bone; eburnation; extension of articular surface by new bone formation; and exostosis around the periphery of the bone. However, the lack of both marginal and articular surface changes (Jurmain and Kilgore 1995, 444) in Yewden specimens makes joint infection a more likely explanation. In horses this kind of interdigital exostosis may be due to a condition known as ring bone, in which lesions occur around the inter-phalangeal joints – Baker and Brothwell (1980, 120-1) link this pathology to repetitive concussion, or “pedal thump”. 22 610005348 The exostosis present on three bovine first phalanges could again indicate OA, however a similar lack of eburnation or grooving on the articular surfaces makes this unlikely. Therefore, it seems most likely that the ossification was caused by infection of the joint, perhaps due to an infection carried to the area in the blood, or a penetrating wound introducing bacteria to the area - Baker and Brothwell (1980, 123) argue that arthropathy like this could indicate a specific interdigital infection such as foul-in-the-foot, a bovine-specific pathology caused by the bacteria Fusiformus necrophorus, in which osteomyelitis (infection of the marrow-cavity) results in pitting of the bone surface. The exostosis affecting the bovine distal metacarpal articulation is also almost certainly the result of infection, specifically spavin. This condition involves periosteal infection of the area, leading to exostosis and often ankylosis of bovine metacarpals and carpals, while leaving the articular surfaces intact, as in this case (Macqueen 1899, 120). A similar case can be seen in a bovine metatarsal from Dragonby (Figure...), where tarsal bones have fused to the distal end of the metatarsal, without affecting the articular surfaces. Such exostosis would cause mild lameness, although in most cases eventual joint ankylosis would allow for the continued, although slightly impeded, use of the joint (Baker and Brothwell 1980, 117-9). Figure...: Bovine metatarsal from Dragonby displaying spavin at the distal end, which has caused the fusion of the metacarpal to the tarsals without affecting articular surfaces. Source: Baker and Brothwell (1980, 119). The abnormal cattle mandible could indicate the presence of “lumpy jaw”; an infection caused by the bacteria Actinomyces bovis which results in an enlarged mandible with protruding osseous growth (Siegel 1976, 365). However, the lack of characteristic “honeycombing” and the localised bony expansion suggests that the osseous growth is in fact the result of a tooth root infection (Baker and Brothwell 1980, 158) It is possible that infection responsible for the osseous growth seen on both horse and cattle specimens could specifically be tuberculosis. The exostosis exhibited may represent the “proliferative periosteal lesions” given by Bendrey (2008, 205) as a typical sign of the condition. However, Baker and Brothwell (1980, 77) maintain that the condition is rare in domestic mammals, and tends to proliferate in the vertebrae, ribs and pelvis due to manifestation of the disease in the respiratory system (Bendrey (2008, 23). As the evidence from Yewden comes from mainly lower leg bones it seems that this diagnosis is unlikely. It is more probable that the observed pathologies are the result of animals being used for draught purposes, especially as they predominantly concern large mammals. The ossification between large mammal vertebrae may represent apophyseal OA, known as “vertebral osteophytosis”, shown by the thickening of the edge of the vertebral body due to the loss of cartilage from the fibro-cartilagenous joints – a condition often associated with 23 610005348 weight-bearing or heavy draught work (Jurmain and Kilgore 1995, 443-8). This interpretation is also supported by the frequency of arthropathy on the lower leg bones consistent with excess workload in draught animals – a phenomenon demonstrated by Daróczi-Szabó (2008, 59) in Roman Balatonlelle-Kenderföld, Hungary, who cites the inflammation of a bovine second phalanx as evidence. Conditions such as ring bone and spavin also point towards repetitive percussion on hard surfaces associated with heavy work (Brothwell and Baker 1980, 118), or animals having been put to work too young (Siegel 1976, 362). (Vann 2008, 35) suggests that pathologies of the lower leg are often over-represented in archaeological assemblages as these elements undergo greater locomotive stress, so are therefore composed of denser bone and are more likely to be preserved. However, abundant pictorial evidence of animals being used for draught work, such as pulling ploughs or carts, on Roman votive monuments, mosaics and reliefs supports the interpretation of the Yewden pathologies being draught-related (De Cupere et al. 2000, 255). It is also suggested that such pathologies could be the result of animals kept in poor conditions or experiencing some kind of neglect (Siegel 1976, 373). Increased susceptibility to disease could have been caused by nutritional deficiency due to less access to grazing or surplus feed, or the presence of parasites in alimentary canal, and specifically lower leg infection may result from prolonged stalling, or keeping animals on soft, muddy pastures (Vann 2008, 33-4). It is likely that that the healed injuries to the bovine calcaneum and tibia, and the dog radius were fractures, as these are commonly seen in Roman archaeological assemblages (Groot 2008, 40). The relative frequency of fractures in the Yewden assemblage is 0.105% although this is slightly higher than Siegel’s (1976, 359-60) estimate of typical frequency (0.04%), a more comparable sample size would be needed to infer significance. The amount of exostosis makes it difficult to identify the type of fracture, however it points towards the breaks being acute, and therefore caused by either direct or indirect trauma (Baker and Brothwell 1980, 85-7). Furthermore, the deformation of the cow tibia suggests malunion during healing due to the angulation of the shaft – the severe exostosis also indicates infection, making it more likely to have been an open fracture where the soft tissue and skin is also injured (Groot 2008, 41-2). This may suggest a lack of human intervention in attempting to treat the fracture and therefore potentially a lack of veterinary knowledge (though Walker (1973, 302-43) argues for comprehensive Roman veterinary knowledge), however the osseous growth suggests that the individual survived the injury (Baker and Brothwell 1980, 85). Additionally, Groot (2008, 48-9) suggests that the fractured dog radius could be as a result of kicks from large animals during hunting or herding, or bites from other dogs, while Teegen (2005, 34-8) goes as far as suggesting human maltreatment, although manifestation predominantly in rib and vertebral fractures makes this less likely at Yewden. 5. Conclusion: economy (based on frequencies/ age and sex/ pathologies): Cattle most important? Does Yewden follow the overall trend of “Romanisation”? o DRAUGHT ANIMALS (PATHOLOGY + SWITCH TO CEREAL PRODUCTION – also prevalence of cattle (Vann 2008, 36). o Cereal production – grain drying kilns! (NOT metalwork!) o Pathology – draught animals/ poor conditions? o Allowed to reach maturity?? 24 610005348 Eaten after use for traction?? – older animals slaughtered? - backed up by BUTCHERY?? sheds any light on brothel interpretation? Infant burials under floors and in farmyards of villas are an indication of infanticide and surreptitious burial (Merrifield 1987, 51), BUT simplistic view! (Scott 1991, 117) – BUT, no evidence from Yewden to suggest that the deposition of animal remains at Yewden has votive associations – examples of ritual burial include deposition in pits or wells; foundation burials, AND patterns such as pairs of heads and feet (e.g. Barnsley Park), solely heads (e.g. Barton Court Farm, Longstock). Furthermore, there does not appear to be any association between the animal remains and the infant burials, unlike sites like Star, where animal and human bone fragments were co-mingled in shallow pits. BUT, Scott (1991, 117-8) also suggests that infant burials spatially associated with animal deposits and “corn driers” in the case of Yewden could point to infanticide and potentially some notion of ritual associated with fertility or rebirth – this is especially the case moving into the fourth century when agricultural products and processing areas became vital to sustaining the villa. OR...women “established ideological links between the female domain and the settlement’s crucial cultural and agricultural activities” (Scott 1991, 120)??? Further work: o take location into account when calculating MNE? – look at distribution of elements as well as species o further consideration of “matching” for MNI – would be easier if taxonomic abundances were calculated while recording took place, as specimens cannot be so easily assessed for age, sex, or size once recording has finished (Reitz and Wing 2008, 206-7; Klein and Cruz-Uribe 1984, 26; Chaplin 1971, 69-75) o ageing of cows?? o It may be useful to take sex in to account in combination with age, for example in the analysis of caprid mandible wear stages or caprid and cattle survival. It may also provide more accuracy in epiphyseal fusion ageing, as the age of fusion is dependent upon sex. Combining age and sex distributions could provide a more useful indication of economy as it would display the dichotomy between male and female mortality profiles, although it may not be possible to garner this information from the assemblage. For example, Greenfield (2002, 69-74) states that sex can be determined successfully from the inominates of ungulates, which are more frequently preserved than conventional sex indicators – this includes measurements like the height, length and width of the acetabulum. o X-rays of fractures useful? (Baker and Brothwell 1980, 91) o Comparison of age (esp. cattle) to pathology – older animals more likely to display pathologies (Siegel 1976, 357), especially lower leg joint disease if used longer for traction? (Vann 2008, 35). o sheep/ goat separation (Maltby 1981, 159-60): metric analysis of metapodials or horns, for example; BUT not all elements can be differentiated! Maltby does argue for goat presence in the Roman period, though, so might be worthwhile. o Metrical analyses (Maltby 1981, 185-92): helpful in determining size of stock, sex and potential importation/exportation of stock by examining regional size variation. (Noddle 1984, 115-22) o 25 610005348 e.g.: cattle – astragalus maximum length; maximum proximal width of metatapodials e.g.: sheep – maximum distal width of tibia 6. Appendices: o o o 6.1: Map of site location, including the associated Mill End villa - MAP! (Eyers and Hutt 2012???) 6.2: Map of site showing main villa complex features source: Cocks (1921, Plate XIII) 6.3: Frequencies table: NISP 26 610005348 27 610005348 Appendix 6.4: Frequencies table: MNE 28 610005348 Appendix 6.5: Frequencies Table: MNI 29