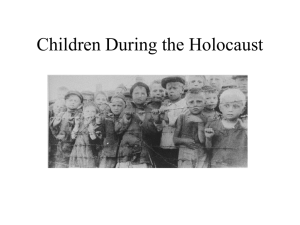

Abstracts 10 July 2013 document - Children and War

advertisement