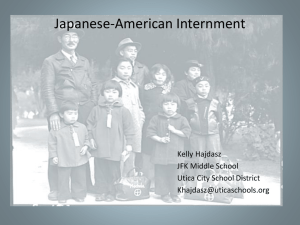

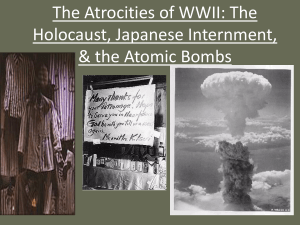

Japanese Internment

advertisement

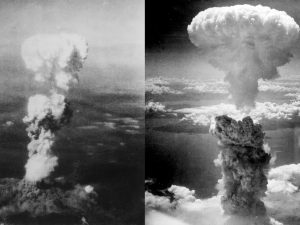

Guided Reading JAPANESE INTERNMENT 1942 - 1945 The Empire of Japan attacked the United States on December 7, 1941. After this attack, the United States entered World War II. As a result, 120,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast were forced from their homes and into internment camps in the United States. A small percentage of people were able to choose their location; the rest were sent to War Relocation Centers. After the Pearl Harbor attack, President Franklin Roosevelt authorized the internment with Executive Order 9066. This allowed local military leaders to assign most military areas as exclusion zones. The order called for the relocation of all people of Japanese descent who lived in California, Oregon, and Washington. Many people felt this decision was unconstitutional; but the Supreme Court upheld the order, stating, “it is permissible to curtail civil rights of a racial group when there is a ‘pressing public necessity.’ ” During this time, there was fear Japanese people living in the United States were working as spies. They were suspected of observing the United States’ strengths and weaknesses and reporting them to the Japanese government. President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The following day, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson designated General John L. Dewitt military commander. His job was to carry out the executive order. He later issued Proclamation No. 1. This designated the western half of California, Oregon, Washington, and the southern part of Arizona as military areas. He also stipulated that anyone of Japanese ancestry would be removed from these areas. On March 11, 1942, the Office of the Alien Property Custodian issued Executive Order 9095. This gave authority over all alien property interests. The financial assets of many Japanese Americans were frozen, which caused economic hardship. Most had no choice but to enter the internment camps. Public Proclamation No. 3 was issued on March 24, 1942. This established a curfew for “all enemy aliens and all persons of Japanese ancestry. This meant they must remain within their military areas from 8 p.m. to 6 a.m. This order included Japanese aliens as well as Japanese-American citizens, many of whom were born in the United States. White farmers in the West welcomed Japanese internment. They saw internment as a way to eliminate farming competitors. Some Japanese Americans were successful farmers in the West. They used economical farming practices they learned in Japan, where resources were limited. These techniques were profitable in the United States. Many believed internment increased Mexican immigration because more farm laborers were needed when Japanese-American farms were confiscated. Labor shortages became more severe as Americans were drafted into the military during World War II. Terminology was important in references to Japanese internment. The United States did not want to appear to mirror Adolf Hitler’s concentration camps in Germany. In a public address on November 21, 1944, President Roosevelt referred to the camps as “concentration camps,” and the term was used in an assortment of government documents. The official government term for the camps became “War Relocation Centers.” The camps were closed and the internees were released in 1945 when World War II ended. Following internment, many Japanese Americans felt they deserved an apology. Many had lost their homes and their businesses. In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement inspired many Japanese-American youths to begin a Redress Movement. They sought an apology and reparations from the United States government. They did not want reparations for property loss, but they wanted reparations for the injustices forced against their families during the war. While president, Gerald Ford proclaimed that internment was “wrong,” but never actually apologized. In the early 1980s, however, the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) decided it was important to study the matter. On February 24, 1983, the commission condemned the internment, stating it was “unjust and motivated by racism rather than real military necessity.” There were no cases of any internees committing any disloyal activity, spying, or sabotage against the United States. In fact, many of the young men in the internment camps joined the United States military and served with distinction fighting in Europe. Finally, in 1988 President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988. According to the act, detainees or the family of detainees were awarded $20,000 each, totaling around $1.2 billion. President George H.W. Bush amended this act in 1992 and increased the award to $1.6 billion. California Representative Norman Mineta and Wyoming Senator Alan K. Simpson sponsored this act in Congress. During the war, Mineta was a Japanese-American Boy Scout interned in Wyoming where he met fellow Boy Scout Alan K. Simpson. The two became close friends and served together in Congress. Japanese Internment of World War Two 1942 - 1945 After completing the Guided Reading, answer the following questions. Be sure to include textual evidence to support your responses. 1. What was Executive Order 9066? 2. What was Proclamation No. 1? 3. What was Executive Order 9095? 4. Who benefited from Japanese internment? Why? 5. What was the Civil Liberties Act of 1988?