"YES" argument sheet

advertisement

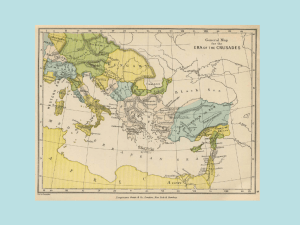

The Origins Of the Crusades by Hans Eberhard Mayer Originally the object of the crusade was to help the Christian Church win the East. However unnecessary such help may, in fact, have been, it was in these terms that Urban (the Pope) is supposed to have spoken at Clermont (when he ordered the First Crusade). But very soon men had a more defined object in mind: to free the Holy Land, and, above all, Jerusalem, the Sepulcher (tomb) of Christ, from the yoke of heathen domination. Even the mere sound of the name Jerusalem must have had a glittering and magical splendor for the men of the eleventh century which we are no longer capable of feeling. It was a keyword which produced particular psychological reactions and conjured up particular eschatological notions (ideas about the end times). Men thought, of course, of the town in Palestine where Jesus Christ had suffered, died, been buried, and then had risen again. But, more than this, they saw in their minds’ eye the heavenly city of Jerusalem with its gates of sapphire, its walls and squares bright with precious stones – as it had been described in the Book of Revelation and Tobias. It was the center of a spiritual world just as the earthly Jerusalem was, in the words of Ezekiel (a Biblical prophet) ‘in the midst of nations and countries’. It was a meeting place for those who had been scattered, the goal of the great pilgrimage of peoples where God resides among his people; the place at the end of time to which the elect ascend (to heaven); the resting place of the righteous; city of paradise and of the tree of life which heals all men… Counting for just as much as the images conjured up by a child-like, mystical faith was the long tradition of pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Monasteries and hospices were built to receive the travellers who, following the new fashion, as it can fairly be called, came to Palestine. The stream of pilgrims never dried up, not even after the Arab conquest of the Holy Land in the seventh century. The growing east-west trade in relics played some part in awakening and sustaining interest in Holy Places, but more important was the gradual development of the penitential pilgrimage. This was imposed as a canonical (church-based) punishment for capital crimes (crimes which would ordinarily bring a death sentence) like fratricide (killing your own brother) that could be for a period of up to seven years and to all the great centers: Rome, San Michele at Monte Gargano, Santiago di Compostella, and, above all, Jerusalem and Bethlehem. With the belief that they were effective ways to salvation the popularity of pilgrimages grew rapidly from the tenth century onwards. For many pilgrims in the eleventh century the journey to Jerusalem took on a still deeper religious meaning; according to Ralph Glaber, himself a Clunaic monk, it was looked upon as the climax of a man’s religious life, as his final journey. Once he had reached the Holy Places he would remain there until he died. It is clear that in the middle of the eleventh century the difficulties facing pilgrims began to increase. In part this was a result of the Seljuk (Muslim Turk) invasions which made things harder for travellers on the road through Anatolia – a popular route because it permitted a visit to Constantinople. But it was also a consequence of the growing number of pilgrims, for this worried the Muslim authorities in Asia Minor and Palestine, just as the Greeks in south Italy looked skeptically upon the groups of Norman (northern European) ‘pilgrims’ who were all too easily persuaded to settled there for good. Here we have reached the critical point of difference between crusader and pilgrim: the crusader carted weapons. A crusade was a pilgrimage but an armed pilgrimage which was granted special privileges by the Church and which was held to be especially meritorious (full of merit). The crusade was a logical extension of the pilgrimage. It would never have occurred to anyone to march out to conquer the Holy Land if men had not made pilgrimages there for century after century. The constant stream of pilgrims inevitably nourished the idea that the Sepulcher of Christ (the tomb of Jesus in Jerusalem) ought to be in Christian hands, not in order to solve the practical difficulties which faced pilgrims, but because gradually the knowledge that the Holy Places, the patrimony of Christ, were possessed by heathens became more and more unbearable. One more motive for taking the cross (going on a crusade) remains to be considered; and this one was to put all the others in the shade. It was the concept of a reward in the form of the crusading indulgence. In modern Roman Catholic doctrine the indulgence come at the end of a clear process of remission of sins. First the penitent sinner (someone seeking forgiveness) must confess and receive absolution so that the guilt of the sin is remitted and instead of suffering eternal punishment he will have to suffer only the temporal (in this world – not in the afterlife) penalties due to sin. (It is important to note that these penalties may take place either in this world or the next and will include purgatory) [Note: purgatory is a temporary place in the afterlife where sins are paid for before one moves on the heaven]. Then in return for indulgenceearning works the Church may grant him remission of all or part of the penalty due to sin. would indeed have been mad. The ‘shrewd businessman’ seized his chance. And who did not want to be numbered among the shrewd? In this context it was important that the penitential journey to Jerusalem was thought to be especially meritorious and salutary. In theory the Church had always taken the view that movement from one place to another did not bring a man any nearer to God; but it was impossible to extinguish the popular belief in the value of pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Glossary: There had been nothing new about being able to obtain remission of penance by going to fight the heathen. But that the penalties due to sin could be remitted simply as a result of taking the cross – as the crusade propagandists suggested – this was an unheard of innovation. It was when linked with the universally popular idea of pilgrimage to Jerusalem that the explosive force of the crusading indulgence was revealed. Ekkehard of Auro spoke of a ‘new way of penance’ now being opened up. Here lies the secret of the astonishing success of (pope) Urban’s summons (to go on a crusade), a success which astonished the Church as much as anyone else. Imagine a knight in the south of France, living with his kinsmen in the socially and economically unsatisfactory institution of frereche. His feuds (conflicts with other Christian knights) and the ‘upper class’ form of highway robbery which often went with them, were prohibited by the Peace of God. Suddenly he was offered a chance to go on a pilgrimage – in any event the wish of many men. This pilgrimage was supervised by the Church; it was moreover an armed pilgrimage during which he could fulfill his knightly function by taking part in battle. There would be opportunities for winning plunder. Above all there was the entirely new offer of a full remission of all the temporal penalties due to sin, especially those to be suffered in purgatory. The absolution given in the sacrament of penance took from him the guilt; taking the cross mean the cancellation of all the punishment even before he set out to perform the task imposed. Not to accept such an offer, not-at the very least- to take it seriously, But the offer of indulgence must have had irresistible attraction for those who did not doubt the Church’s teaching, who believed in the reality of the penalties due to sin, or at least accepted the possibility of their existence. Such believers must have made up a great part of those who went on the First Crusade… Eschatological: Having to do with the end times (e.g. the second coming of Christ and end of the world) Relic: a remnant of the body of a saint (or holy person) or something involved in their myth, e.g. a piece of the cross on which Jesus was crucified. Fratricide: Killing a brother. Canonical: Of the church, e.g. Canonical law was a separate set of laws passed and enforced by the Catholic Church. Seljuk (Turks): Central Asian nomads who converted to Islam and conquered much of the Middle East, including Jerusalem. Normans: Western Europeans. Also sometimes called “Latins”. Indulgence: Partial forgiveness for a sin granted by the church in return for extraordinary service. If granted one would spend less time in purgatory before going to heaven. Penitent: Someone who is seeking forgiveness for a sin. Absolution: Receiving forgiveness for a sin. Temporal: Having to do with this life (and not the afterlife). Frereche: The feudal economy where serfs served lords in a primarily agricultural (and therefore limited in opportunity) economy. One of the only means to increasing wealth for Lords was to squeeze the peasants for more. Peace of God: A movement initiated by the pope that forbade mortal combat between Christian knights. Excerpted from Mitchell, J.R. & Mitchell, H.B. (2002). Taking Sides: Clashing Views of Controversial Issues in World History. Volume I. McGraw-Hill Dushkin. Guilford, CT. pp 154-164. In-text vocabulary clarifications added to original text.