The Garbage Collector (GC) - Inchcape Shipping Services

advertisement

How the Garbage Collector works - Part 1

The Garbage Collector (GC) can be considered the heart of the .NET Framework. It manages

the allocation and release of memory for any .NET application. In order to create good .NET

applications, we must know how the Garbage Collector (GC) works.

Basic rules

The Garbage Collector (GC) can’t be controlled by the application.

All garbage-collectable objects are allocated from one contiguous range of address

space and are grouped by age.

There are never any gaps between objects in the managed heap.

The order of objects in memory remains the order in which they were created.

The oldest objects are at the lowest addresses (managed heap bottom), while new

objects are created at increasing addresses (managed heap top).

Periodically the managed heap is compacted by removing dead objects and sliding the

live objects up toward the low-address end of the heap.

Determine which object is dead

Don’t confuse the created objects with the references that point them (pointers)! Let’s consider

the following code sample:

string s1 = "STRING";

string s2 = "STRING";

Here, "s1" and "s2" are not the created string objects! The code above creates only one string

object ("STRING") due the intern mechanism. Please read more about interned strings in this

article: How to: Optimize the memory usage with strings. The "s1" and "s2" are just references

to the same string object (just pointers).

The object remains on the heap until it's no longer referenced by any active code, at which

point the memory it's using is reclaimed by the Garbage Collector (GC).

Even if one of the two references is set to null, the Garbage Collector (GC) will be still

considering the "STRING" object to be alive because the other reference is pointing to it.

The GC generations

All the living objects from the managed heap are divided in three groups by their age. Those

groups are generically called "Generations". Those generations are very useful to prevent

memory fragmentation on the managed heap. The Garbage Collector (GC) can search for dead

object on each generation at a time (partial collections), to improve the collecting

performance.

Now let’s see what the Garbage Collector (GC) is using each generation for:

Generation 0 (Gen0) contains all the newly created objects and it is located on the top

of the heap zone (higher memory addresses). All the objects contained by Gen0 are

considered short-lived object and the Garbage Collector (GC) is expecting to them to be

quickly destroyed in order to release the used memory space. Due to this presumption,

the Garbage Collector (GC) will try to collect dead objects most often from Gen0

because it is cheapest.

Generation 1 (Gen1) contains all the living objects from Gen0 that have survived to

several Gen0 collects. So those objects are upgraded from Generation 0 to Generation

1. Gen1 is defined in the middle of the heap zone and it is exposed to fewer garbage

collects than Gen0. Gen1’s collects are more expensive than the Gen0’s so the Garbage

Collector (GC) will try to avoid them if it is not really necessary.

Generation 2 (Gen2) contains all the living objects from Gen1 that have survived to

several Gen2 collects. Those objects are considered long-lived objects and destroying

them is very expensive. Because of this, the Garbage Collector (GC) will hardly try to

collect them. The Gen2 zone is located on the bottom of the managed heap zone

(lowest memory addresses).

How to: Optimize the memory usage with strings

The System.String type is basically a sequence of Unicode characters. Some of the most important

properties of the String type are:

It is immutable. Once a string is created it can not be modified. Updating the string’s value will

end up in creating a new string object having the updated content and reclaiming the old string

by the GC (Garbage Collector)

It is a reference type. Because of the immutability, many people think that the String is a value

type. Actually it is a reference type, so a string can be null. Being a reference type is a good

think, because we can save memory by sharing same object references for long strings having

same content. A null string is not equivalent with an empty string!

It overloads the == operator. When the == operator is used, the Equals() method is called. This

will check first if the compared strings share same object. If is so, the Equals() method will skip

checking the content and it will return True. If the two strings are referring different objects, a

content based comparison will start. So for the first scenario, the Equals() method is much

faster. You can read more about comparing strings here: How to: Optimize the strings’

comparison

Preserve memory

System.String type is used in any .NET application. We have strings as: names, addresses, descriptions,

error messages, warnings or even application settings. Each application has to create, compare or

format string data. Considering the immutability and the fact that any object can be converted to a

string, all the available memory can be swallowed by a huge amount of unwanted string duplicates or

unclaimed string objects. Now let's see how a string object should be handled to preserve memory.

String literals

Using literals guaranties that strings with same content are using references to same string objects.

C# .NET

string literal1 = "STRING";

string literal2 = "STRING";

Console.WriteLine("literal1 = {0}", literal1);

Console.WriteLine("literal2 = {0}", literal2);

if (Object.ReferenceEquals(literal1, literal2))

{

// Are sharing same object...

}

This is where an often overlooked technique called string interning comes into play. Each .NET assembly

has an intern pool, which is in essence a collection of unique strings. When your code is compiled, all

the string literals you reference in your code are added to this pool. Since many literals in a program

tend to appear in multiple places, this conserves memory.

Concatenated literals are using the intern pool too:

C# .NET

// Are sharing the same object!

string string1 = "My" + " " + "STRING";

string string2 = "My STRING";

String constants

The string constants give you same effect because the compiler will replace all constant refecences with

the defined string literals.

String.Empty vs ""

Use String.Empty rather than "". This is more for speed than memory usage but it is a useful tip. The "" is

a literal so will act as a literal: on the first use it is created and for the following uses its reference is

returned. Only one instance of "" will be stored in memory no matter how many times we use it! I don't

see any memory penalties here. The problem is that each time the "" is used, a comparing loop is

executed to check if the "" is already in the intern pool. On the other side, String.Empty is a reference to

a "" stored in the .NET Framework memory zone. String.Empty is pointing to same memory address for

VB.NET and C# applications. So why search for a reference each time you need "" when you have that

reference in String.Empty?

C# .NET

// Are NOT sharing same object!

string empty1 = "";

string empty2 = String.Empty;

String = String

If a string is initialized with a precreated string, both will share same object.

C# .NET

// Are sharing the same object!

string string1 = "STRING";

string string2 = string1;

Updating any of them will end up in creating two different string objects:

C# .NET

string1 = "UPDATED STRING";

Now string1 is pointing to the new created string ("UPDATED STRING") while string2 is pointing to the

old string object ("STRING").

The String.Concat() method

The String.Concat() method is creating new string objects for each call. So, strings created by this

method will never share same object even if they have same content:

C# .NET

// Two different objects are created!

string concat1 = String.Concat("My", " ", "String");

string concat2 = String.Concat("My", " ", "String");

The StringBuilder class

This is also true for using the StringBuilder class:

C# .NET

StringBuilder stringBuilder1 = new StringBuilder();

stringBuilder1.Append("String");

StringBuilder stringBuilder2 = new StringBuilder();

stringBuilder2.Append("String");

// Two different objects are created!

string sb1 = stringBuilder1.ToString();

string sb2 = stringBuilder2.ToString();

String created at run-time

Strings created at run-time don't share same objects:

C# .NET

// Two different objects are created!

string runTime1 = Char.ConvertFromUtf32(200);

string runTime2 = Char.ConvertFromUtf32(200);

The String.Intern() method

The strings created at run-time can behave like literals if the String.Intern() method is used. The Intern

method uses the intern pool to search for a string equal to the value of argument. If such a string exists,

its reference in the intern pool is returned. If the string does not exist, a reference to argument is added

to the intern pool, then that reference is returned. Note that searching for a string in the intern pool can

be expensive, depending how many strings are in the pool at that time.

C# .NET

// Are sharing the same object!

string interned1 = String.Intern(Char.ConvertFromUtf32(200));

string interned2 = String.Intern(Char.ConvertFromUtf32(200));

Keep in mind that interning a string has two unwanted side effects:

The memory allocated for interned String objects is not likely be released until the Common

Language Runtime (CLR) terminates. The reason is that the CLR's reference to the interned

String object can persist after your application, or even your application domain, terminates.

To intern a string, you must first create the string. The memory used by the String object must

still be allocated, even though the memory will eventually be garbage collected.

Introduction

In order to understand how to make good use of the garbage collector and what performance

problems you might run into when running in a garbage-collected environment, it's important

to understand the basics of how garbage collectors work and how those inner workings affect

running programs.

This article is broken down into two parts: First I will discuss the nature of the common

language runtime (CLR)'s garbage collector in general terms using a simplified model, and then I

will discuss some performance implications of that structure.

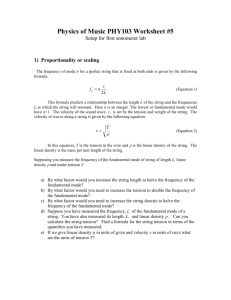

Simplified Model

For explanatory purposes, consider the following simplified model of the managed heap. Note

that this is not what is actually implemented.

Figure 1. Simplified model of the managed heap

The rules for this simplified model are as follows:

All garbage-collectable objects are allocated from one contiguous range of address space.

The heap is divided into generations (more on this later) so that it is possible to eliminate most

of the garbage by looking at only a small fraction of the heap.

Objects within a generation are all roughly the same age.

Higher-numbered generations indicate areas of the heap with older objects—those objects are

much more likely to be stable.

The oldest objects are at the lowest addresses, while new objects are created at increasing

addresses. (Addresses are increasing going down in Figure 1 above.)

The allocation pointer for new objects marks the boundary between the used (allocated) and

unused (free) areas of memory.

Periodically the heap is compacted by removing dead objects and sliding the live objects up

toward the low-address end of the heap. This expands the unused area at the bottom of the

diagram in which new objects are created.

The order of objects in memory remains the order in which they were created, for good locality.

There are never any gaps between objects in the heap.

Only some of the free space is committed. When necessary,more memory is acquired from the

operating system in the reserved address range.

Collecting the Garbage

The easiest kind of collection to understand is the fully compacting garbage collection, so I'll

begin by discussing that.

Full Collections

In a full collection we must stop the program execution and find all of the roots into the GC

heap. These roots come in a variety of forms, but are most notably stack and global variables

that point into the heap. Starting from the roots, we visit every object and follow every object

pointer contained in every visited object marking the objects as we go along. In this way the

collector will have found every reachable or live object. The other objects, the unreachable

ones, are now condemned.

Figure 2. Roots into the GC heap

Once the unreachable objects have been identified we want to reclaim that space for later use;

the goal of the collector at this point is to slide the live objects up and eliminate the wasted

space. With execution stopped, it's safe for the collector to move all those objects, and to fix all

the pointers so that everything is properly linked in its new location. The surviving objects are

promoted to the next generation number (which is to say the boundaries for the generations

are updated) and execution can resume.

Partial Collections

Unfortunately, the full garbage collection is simply too expensive to do every time, so now it's

appropriate to discuss how having generations in the collection helps us out.

First let's consider an imaginary case where we are extraordinarily lucky. Let's suppose that

there was a recent full collection and the heap is nicely compacted. Program execution resumes

and some allocations happen. In fact, lots and lots of allocations happen and after enough

allocations the memory management system decides it's time to collect.

Now here's where we get lucky. Suppose that in all of the time we were running since the last

collection we didn't write on any of the older objects at all, only newly allocated, generation

zero (gen0), objects have been written to. If this were to happen we would be in a great

situation because we can simplify the garbage collection process massively.

Instead of our usual full collect we can just assume that all of the older objects (gen 1, gen2) are

still live—or at least enough of them are alive that it isn't worth looking at those objects.

Furthermore, since none of them were written (remember how lucky we are?) there are no

pointers from the older objects to the newer objects. So what we can do is look at all the roots

like usual, and if any roots point to old objects just ignore those ones. For other roots (those

pointing into gen0) we proceed as usual, following all the pointers. Whenever we find an

internal pointer that goes back into the older objects, we ignore it.

When that process is done we will have visited every live object in gen 0 without having visited

any objects from the older generations. The gen0 objects can then be condemned as usual and

we slide up just that region of memory, leaving the older objects undisturbed.

Now this is really a great situation for us because we know that most of the dead space is likely

to be in younger objects where there is a great deal of churn. Many classes create temporary

objects for their return values, temporary strings, and assorted other utility classes like

enumerators and whatnot. Looking at just gen0 gives us an easy way to get back most of the

dead space by looking at only very few of the objects.

Unfortunately, we're never lucky enough to use this approach, because at least some older

objects are bound to change so that they point to new objects. If that happens it's not sufficient

to just ignore them.

Making Generations Work with Write Barriers

To make the algorithm above actually work, we must know which older objects have been

modified. To remember the location of the dirty objects, we use a data structure called the card

table, and to maintain this data structure the managed code compiler generates so-called write

barriers. These two notions are central the success of generation-based garbage collecting.

The card table can be implemented in a variety of ways, but the easiest way to think of it is as

an array of bits. Each bit in the card table represents a range of memory on the heap—let's say

128 bytes. Every time a program writes an object into some address, the write barrier code

must compute which 128-byte chunk was written and then set the corresponding bit in the card

table.

With this mechanism in place, we can now revisit the collection algorithm. If we are doing a

gen0 garbage collection, we can use the algorithm as discussed above, ignoring any pointers to

older generations, but once we have done that we must then also find every object pointer in

every object that lies on a chunk that was marked as modified in the card table. We must treat

those just like roots. If we consider those pointers as well, then we will correctly collect just the

gen0 objects.

This approach wouldn't help at all if the card table was always full, but in practice comparatively

few of the pointers from the older generations actually get modified, so there is a substantial

savings from this approach.

Performance

Now that we have a basic model for how things are working, let's consider some things that

could go wrong that would make it slow. That will give us a good idea what sorts of things we

should try to avoid to get the best performance out of the collector.

Too Many Allocations

This is really the most basic thing that can go wrong. Allocating new memory with the garbage

collector is really quite fast. As you can see in Figure 2 above is all that needs to happen

typically is for the allocation pointer to get moved to create space for your new object on the

"allocated" side—it doesn't get much faster than that. However, sooner or later a garbage

collect has to happen and, all things being equal, it's better for that to happen later than

sooner. So you want to make sure when you're creating new objects that it's really necessary

and appropriate to do so, even though creating just one is fast.

This may sound like obvious advice, but actually it's remarkably easy to forget that one little line

of code you write could trigger a lot of allocations. For example, suppose you're writing a

comparison function of some kind, and suppose that your objects have a keywords field and

that you want your comparison to be case insensitive on the keywords in the order given. Now

in this case you can't just compare the entire keywords string, because the first keyword might

be very short. It would be tempting to use String.Split to break the keyword string into pieces

and then compare each piece in order using the normal case-insensitive compare. Sounds great

right?

Well, as it turns out doing it like that isn't such a good idea. You see, String.Split is going to

create an array of strings, which means one new string object for every keyword originally in

your keywords string plus one more object for the array. Yikes! If we're doing this in the context

of a sort, that's a lot of comparisons and your two-line comparison function is now creating a

very large number of temporary objects. Suddenly the garbage collector is going to be working

very hard on your behalf, and even with the cleverest collection scheme there is just a lot of

trash to clean up. Better to write a comparison function that doesn't require the allocations at

all.

Too-Large Allocations

When working with a traditional allocator, such as malloc(), programmers often write code that

makes as few calls to malloc() as possible because they know the cost of allocation is

comparatively high. This translates into the practice of allocating in chunks, often speculatively

allocating objects we might need, so that we can do fewer total allocations. The pre-allocated

objects are then manually managed from some kind of pool, effectively creating a sort of highspeed custom allocator.

In the managed world this practice is much less compelling for several reasons:

First, the cost of doing an allocation is extremely low—there's no searching for free blocks as

with traditional allocators; all that needs to happen is the boundary between the free and

allocated areas needs to move. The low cost of allocation means that the most compelling

reason to pool simply isn't present.

Second, if you do choose to pre-allocate you will of course be making more allocations than are

required for your immediate needs, which could in turn force additional garbage collections

that might otherwise have been unnecessary.

Finally, the garbage collector will be unable to reclaim space for objects that you are manually

recycling, because from the global perspective all of those objects, including the ones that are

not currently in use, are still live. You might find that a great deal of memory is wasted keeping

ready-to-use but not in-use objects on hand.

This isn't to say that pre-allocating is always a bad idea. You might wish to do it to force certain

objects to be initially allocated together, for instance, but you will likely find it is less compelling

as a general strategy than it would be in unmanaged code.

Too Many Pointers

If you create a data structure that is a large mesh of pointers you'll have two problems. First,

there will be a lot of object writes (see Figure 3 below) and, secondly, when it comes time to

collect that data structure, you will make the garbage collector follow all those pointers and if

necessary change them all as things move around. If your data structure is long-lived and won't

change much, then the collector will only need to visit all those pointers when full collections

happen (at the gen2 level). But if you create such a structure on a transitory basis, say as part of

processing transactions, then you will pay the cost much more often.

Figure 3. Data structure heavy in pointers

Data structures that are heavy in pointers can have other problems as well, not related to

garbage collection time. Again, as we discussed earlier, when objects are created they are

allocated contiguously in the order of allocation. This is great if you are creating a large,

possibly complex, data structure by, for instance, restoring information from a file. Even though

you have disparate data types, all your objects will be close together in memory, which in turn

will help the processor to have fast access to those objects. However, as time passes and your

data structure is modified, new objects will likely need to be attached to the old objects. Those

new objects will have been created much later and so will not be near the original objects in

memory. Even when the garbage collector does compact your memory your objects will not be

shuffled around in memory, they merely "slide" together to remove the wasted space. The

resulting disorder might get so bad over time that you may be inclined to make a fresh copy of

your whole data structure, all nicely packed, and let the old disorderly one be condemned by

the collector in due course.

Too Many Roots

The garbage collector must of course give roots special treatment at collection time—they

always have to be enumerated and duly considered in turn. The gen 0 collection can be fast only

to the extent that you don't give it a flood of roots to consider. If you were to create a deeply

recursive function that has many object pointers among its local variables, the result can

actually be quite costly. This cost is incurred not only in having to consider all those roots, but

also in the extra-large number of gen0 objects that those roots might be keeping alive for not

very long (discussed below).

Too Many Object Writes

Once again referring to our earlier discussion, remember that every time a managed program

modified an object pointer the write barrier code is also triggered. This can be bad for two

reasons:

First, the cost of the write barrier might be comparable to the cost of what you were trying to

do in the first place. If you are, for instance, doing simple operations in some kind of

enumerator class, you might find that you need to move some of your key pointers from the

main collection into the enumerator at every step. This is actually something you might want to

avoid, because you effectively double the cost of copying those pointers around due to the

write barrier and you might have to do it one or more times per loop on the enumerator.

Second, triggering write barriers is doubly bad if you are in fact writing on older objects. As you

modify your older objects you effectively create additional roots to check (discussed above)

when the next garbage collection happens. If you modified enough of your old objects you

would effectively negate the usual speed improvements associated with collecting only the

youngest generation.

These two reasons are of course complemented by the usual reasons for not doing too many

writes in any kind of program. All things being equal, it's better to touch less of your memory

(read or write, in fact) so as to make more economical use of the processor's cache.

Too Many Almost-Long-Life Objects

Finally, perhaps the biggest pitfall of the generational garbage collector is the creation of many

objects, which are neither exactly temporary nor are they exactly long-lived. These objects can

cause a lot of trouble, because they will not be cleaned up by a gen0 collection (the cheapest),

as they will still be necessary, and they might even survive a gen1 collection because they are

still in use, but they soon die after that.

The trouble is, once an object has arrived at the gen2 level, only a full collection will get rid of it,

and full collections are sufficiently costly that the garbage collector delays them as long as is

reasonably possible. So the result of having many "almost-long-lived" objects is that your gen2

will tend to grow, potentially at an alarming rate; it might not get cleaned up nearly as fast as

you would like, and when it does get cleaned up it will certainly be a lot more costly to do so

than you might have wished.

To avoid these kinds of objects, your best lines of defense go like this:

1. Allocate as few objects as possible, with due attention to the amount of temporary space you

are using.

2. Keep the longer-lived object sizes to a minimum.

3. Keep as few object pointers on your stack as possible (those are roots).

If you do these things, your gen0 collections are more likely to be highly effective, and gen1 will

not grow very fast. As a result, gen1 collections can be done less frequently and, when it

becomes prudent to do a gen1 collection, your medium lifetime objects will already be dead and

can be recovered, cheaply, at that time.

If things are going great then during steady-state operations your gen2 size will not be

increasing at all!

Finalization

Now that we've covered a few topics with the simplified allocation model, I'd like to complicate

things a little bit so that we can discuss one more important phenomenon, and that is the cost

of finalizers and finalization. Briefly, a finalizer can be present in any class—it's an optional

member that the garbage collector promises to call on otherwise dead objects before it

reclaims the memory for that object. In C# you use the ~Class syntax to specify the finalizer.

How Finalization Affects Collection

When the garbage collector first encounters an object that is otherwise dead but still needs to

be finalized it must abandon its attempt to reclaim the space for that object at that time. The

object is instead added to a list of objects needing finalization and, furthermore, the collector

must then ensure that all of the pointers within the object remain valid until finalization is

complete. This is basically the same thing as saying that every object in need of finalization is

like a temporary root object from the collector's perspective.

Once the collection is complete, the aptly named finalization thread will go through the list of

objects needing finalization and invoke the finalizers. When this is done the objects once again

become dead and will be naturally collected in the normal way.

Finalization and Performance

With this basic understanding of finalization we can already deduce some very important

things:

First, objects that need finalization live longer than objects that do not. In fact, they can live a

lot longer. For instance, suppose an object that is in gen2 needs to be finalized. Finalization will

be scheduled but the object is still in gen2, so it will not be re-collected until the next gen2

collection happens. That could be a very long time indeed, and, in fact, if things are going well it

will be a long time, because gen2 collections are costly and thus we want them to happen very

infrequently. Older objects needing finalization might have to wait for dozens if not hundreds of

gen0 collections before their space is reclaimed.

Second, objects that need finalization cause collateral damage. Since the internal object

pointers must remain valid, not only will the objects directly needing finalization linger in

memory but everything the object refers to, directly and indirectly, will also remain in memory.

If a huge tree of objects was anchored by a single object that required finalization, then the

entire tree would linger, potentially for a long time as we just discussed. It is therefore

important to use finalizers sparingly and place them on objects that have as few internal object

pointers as possible. In the tree example I just gave, you can easily avoid the problem by

moving the resources in need of finalization to a separate object and keeping a reference to

that object in the root of the tree. With that modest change only the one object (hopefully a

nice small object) would linger and the finalization cost is minimized.

Finally, objects needing finalization create work for the finalizer thread. If your finalization

process is a complex one, the one and only finalizer thread will be spending a lot of time

performing those steps, which can cause a backlog of work and therefore cause more objects to

linger waiting for finalization. Therefore, it is vitally important that finalizers do as little work as

possible. Remember also that although all object pointers remain valid during finalization, it

might be the case that those pointers lead to objects that have already been finalized and

might therefore be less than useful. It is generally safest to avoid following object pointers in

finalization code even though the pointers are valid. A safe, short finalization code path is the

best.

IDisposable and Dispose

In many cases it is possible for objects that would otherwise always need to be finalized to

avoid that cost by implementing the IDisposable interface. This interface provides an

alternative method for reclaiming resources whose lifetime is well known to the programmer,

and that actually happens quite a bit. Of course it's better still if your objects simply use only

memory and therefore require no finalization or disposing at all; but if finalization is necessary

and there are many cases where explicit management of your objects is easy and practical, then

implementing the IDisposable interface is a great way to avoid, or at least reduce, finalization

costs.

In C# parlance, this pattern can be quite a useful one:

Copy

class X: IDisposable

{

public X(…)

{

… initialize resources …

}

~X()

{

… release resources …

}

public void Dispose()

{

// this is the same as calling ~X()

Finalize();

// no need to finalize later

System.GC.SuppressFinalize(this);

}

};

Where a manual call to Dispose obviates the need for the collector to keep the object alive and

call the finalizer.

Conclusion

The .NET garbage collector provides a high-speed allocation service with good use of memory

and no long-term fragmentation problems, however it is possible to do things that will give you

much less than optimal performance.

To get the best out of the allocator you should consider practices such as the following:

Allocate all of the memory (or as much as possible) to be used with a given data structure at the

same time.

Remove temporary allocations that can be avoided with little penalty in complexity.

Minimize the number of times object pointers get written, especially those writes made to older

objects.

Reduce the density of pointers in your data structures.

Make limited use of finalizers, and then only on "leaf" objects, as much as possible. Break

objects if necessary to help with this.

A regular practice of reviewing your key data structures and conducting memory usage profiles

with tools like Allocation Profiler will go a long way to keeping your memory usage effective and

having the garbage collector working its best for you.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Memory Management

One of the main sources of nasty, difficult- to finds bug on modern application is incorrect use

of manual memory management. Like in C++, programmer would create an object and forget to

delete it when they finished using it. This seemingly simple paradigm has been one of the major

sources of programming errors. After all, how many times have you forgotten to free memory

when it is no longer needed or attempted to use memory after you've already freed it? These

leaks eventually consumed a process's entire memory space and caused it to crash.

Garbage Collection

Microsoft has made automatic memory management part of the .NET CLR, which allows it to be

used from any .NET language. A programmer creates an object using the new operator and

receives a reference to it. The CLR allocate that object's memory from managed heap. The

Microsoft.NET common language runtime requires that all resources be allocated from the

managed heap. An object to which all the references have been disappeared is called garbage

and removed from heap. This entire operation is called garbage collection. In managed heap

objects are automatically freed when they are no longer needed by the application. This, of

course, raises the question: how does the managed heap know when an object is no longer in

use by the application?

The Question

How does the garbage collector know if the application is using an object or not? It is not a

simple question to answer. If any object exists, which is no longer used by any application, then

the memory used by these objects can be reclaimed.

Application Root

Every application has a set of roots. Roots identify storage locations, which refer to objects on

the managed heap or to objects that are set to null. For example, all the global and static object

pointers in an application are considered part of the application's roots. In addition, any local

variable/parameter object pointers on a thread's stack are considered part of the application's

roots. Finally, any CPU registers containing pointers to objects in the managed heap are also

considered part of the application's roots. The list of active roots is maintained by the just-intime (JIT) compiler and common language runtime, and is made accessible to the garbage

collector's algorithm.

The Algorithm

GCs only occur when the heap is full. When the garbage collector starts running, it makes the

assumption that all objects in the heap are garbage. In other words, it assumes that none of the

application's roots refer to any objects in the heap. Now, the garbage collector starts walking

the roots and building a graph of all objects reachable from the roots. For example, the garbage

collector may locate a global variable that points to an object in the heap.

Following Figure shows a heap with several allocated objects where the application roots 1

refer directly to objects Obj1, Obj2 and application root 2 refer to Obj4 and obj5. All of these

objects become part of the graph. When adding object Obj2 of application root 1, the collector

notices that this object refers to object Obj7 is also added to the graph. The collector continues

to walk through all reachable objects recursively.

Garbage collector checks the all application roots and walks the objects again. As the garbage

collector walks from object to object, if it attempts to add an object to the graph that it

previously added, then the garbage collector can stop walking down that path. This serves two

purposes. First, it helps performance significantly since it doesn't walk through a set of objects

more than once. Second, it prevents infinite loops should you have any circular linked lists of

objects.

Once all the roots have been checked, the garbage collector's graph contains the set of all

objects that are somehow reachable from the application's roots; any objects that are not in

the graph are not accessible by the application, and are therefore considered garbage. The

garbage collector now walks through the heap linearly, looking for contiguous blocks of garbage

objects (now considered free space). The garbage collector then shifts the non-garbage objects

down in, removing all of the gaps in the heap. Of course, moving the objects in memory

invalidates all pointers to the objects. So the garbage collector must modify the application's

roots so that the pointers point to the objects' new locations. In addition, if any object contains

a pointer to another object, the garbage collector is responsible for correcting these pointers as

well.

After all the garbage has been identified, all the non-garbage has been compacted, and all the

non-garbage pointers have been fixed-up, the NextObjPtr is positioned just after the last nongarbage object. At this point, the new operation is tried again and the resource requested by

the application is successfully created.

There are a few important things to note at this point. You no longer have to implement any

code that manages the lifetime of any resources that your application uses. It is not possible to

leak resources, since any resource not accessible from your application's roots can be collected

at some point. Second, it is not possible to access a resource that is freed, since the resource

won't be freed if it is reachable. If it's not reachable, then your application has no way to access

it.

Finalization

The garbage collector offers an additional feature that you may want to take advantage of:

finalization. Finalization allows a resource to gracefully clean up after itself when it is being

collected. By using finalization, a resource representing a file or network connection is able to

clean itself up properly when the garbage collector decides to free the resource's memory.

Conclusion

The motivation for garbage-collected environments is to simplify memory management for the

developer. Garbage collection algorithm shows how resources are allocated, how automatic

garbage collection works, how to use the finalization feature to allow an object to clean up

after itself.