Executive Summary

advertisement

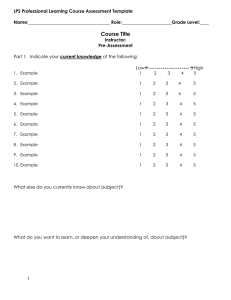

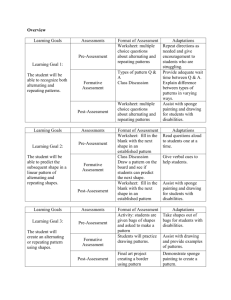

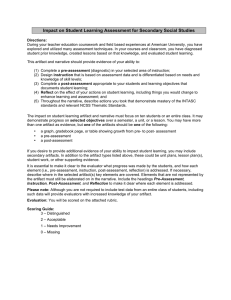

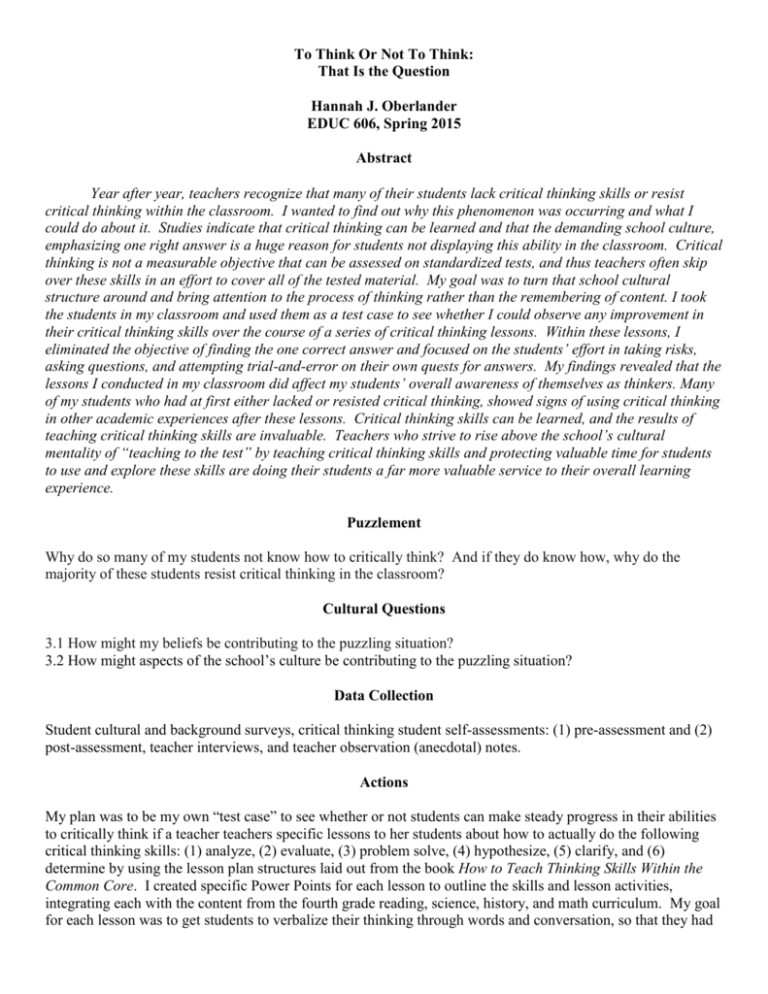

To Think Or Not To Think: That Is the Question Hannah J. Oberlander EDUC 606, Spring 2015 Abstract Year after year, teachers recognize that many of their students lack critical thinking skills or resist critical thinking within the classroom. I wanted to find out why this phenomenon was occurring and what I could do about it. Studies indicate that critical thinking can be learned and that the demanding school culture, emphasizing one right answer is a huge reason for students not displaying this ability in the classroom. Critical thinking is not a measurable objective that can be assessed on standardized tests, and thus teachers often skip over these skills in an effort to cover all of the tested material. My goal was to turn that school cultural structure around and bring attention to the process of thinking rather than the remembering of content. I took the students in my classroom and used them as a test case to see whether I could observe any improvement in their critical thinking skills over the course of a series of critical thinking lessons. Within these lessons, I eliminated the objective of finding the one correct answer and focused on the students’ effort in taking risks, asking questions, and attempting trial-and-error on their own quests for answers. My findings revealed that the lessons I conducted in my classroom did affect my students’ overall awareness of themselves as thinkers. Many of my students who had at first either lacked or resisted critical thinking, showed signs of using critical thinking in other academic experiences after these lessons. Critical thinking skills can be learned, and the results of teaching critical thinking skills are invaluable. Teachers who strive to rise above the school’s cultural mentality of “teaching to the test” by teaching critical thinking skills and protecting valuable time for students to use and explore these skills are doing their students a far more valuable service to their overall learning experience. Puzzlement Why do so many of my students not know how to critically think? And if they do know how, why do the majority of these students resist critical thinking in the classroom? Cultural Questions 3.1 How might my beliefs be contributing to the puzzling situation? 3.2 How might aspects of the school’s culture be contributing to the puzzling situation? Data Collection Student cultural and background surveys, critical thinking student self-assessments: (1) pre-assessment and (2) post-assessment, teacher interviews, and teacher observation (anecdotal) notes. Actions My plan was to be my own “test case” to see whether or not students can make steady progress in their abilities to critically think if a teacher teachers specific lessons to her students about how to actually do the following critical thinking skills: (1) analyze, (2) evaluate, (3) problem solve, (4) hypothesize, (5) clarify, and (6) determine by using the lesson plan structures laid out from the book How to Teach Thinking Skills Within the Common Core. I created specific Power Points for each lesson to outline the skills and lesson activities, integrating each with the content from the fourth grade reading, science, history, and math curriculum. My goal for each lesson was to get students to verbalize their thinking through words and conversation, so that they had ideas to write down when they needed to show their thinking through written responses. Each lesson ended with a reflection that the students would think and write their “take away” from the experiences. Findings Through teaching the critical thinking lessons, the glaring truth that has come to light is that students are hesitant and resistant to exert effort in trying to critically think if they sense the threat that they may be wrong. My biggest takeaway from this experience is that teaching critical thinking lessons has a bigger impact on students than I ever thought that it would. When I compared the pre-assessment to the post-assessment results, my students showed significant gains from having been taught the six critical thinking lessons laid out in my Action Plan. In responding to all eight questions in the self-assessment, the answer average increased. Critical thinking can be learned, and this data provides proof that explicit instruction of critical thinking skills along with guided practice and hands-on experiences that engage students in the process of thinking significantly affect student perceptions of themselves as thinkers (Klemm, 2011, p. 1). I also have noticed that students view themselves as thinkers in a more positive light—as I have stressed in all of the lessons how important putting forth the effort is rather than just a quick, right answer that no thought was given to (Klemm, 2011, p. 2). In addition, I see students beginning to embrace the “struggle” of thinking with less resistance, because they are aware that this is linked with the learning experience. Comparisons Between the Results of Student Pre and Post Assessments 4.5 4 3.5 3 2.5 Pre-Assessment Results 2 1.5 Post-Assessment Results 1 0.5 0 Q1 Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q7 Q8 Conclusions Critical thinking takes time for students to learn and practice. The amount of time needed to conduct the critical thinking lessons and the pacing of the content are at odds with one another. School culture currently prevents and in many ways prohibits students from critically thinking (Jacob, 1999, p. 1). As long as the high-stakes, standardized testing band wagon continues to convince well-meaning citizens, law makers, and even educators that the results of those tests indicate an ability to learn, students will continue to lack these skills. No matter how challenging it may be to bring the truths to light that testing is not the answer to making our students learn more or make our teachers teach better, teachers need to develop professional capital so that we can join forces in a valiant effort to shake the school culture that is truly holding us back. References Bellanca, J. A., Fogarty, R., & Pete, B. M. (2012). How to teach thinking skills within the common core: 7 key student proficiencies of the new national standards. Bernstein, K. (2013). Warnings from the trenches. Acadme Journal of the American Association of University Professors, 99(1). Retrieved from http://www.aaup.org/article/warnings-trenches#.VT0H_2TF-Ad Berube, C. T. (2004). Are standards preventing good teaching? The Clearing House, 77(6), 264-67. Connerly, D. (2006). Teaching critical thinking skills to fourth grade students identified as gifted and talented. Masters Thesis Graceland University, Cedar Rapids, IA. Conti, G. (2013). Teacher’s resignation letter: ‘My profession. . . no longer exists.’ Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/answer-sheet/wp/2013/04/06/teachers-resignation-letter-myprofession-no-longer-exists/ Datnow, A. & Park, V. (2015). Data use for equity: meaningful use of data in school means giving all students the opportunity to achieve at high levels. Educational Leadership, 72(5), 49-54. Elder, L. & Paul, R. W. (1999). Critical thinking: Basic theory and instructional structures handbook. Tomales, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking. Falk, B., & Blumenreich, M. (2005). The power of questions: A guide to teacher and student research. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Freire, Paulo. (2008). “The “banking” concept of education”: Ways of reading. By David Bartholomae and Anthony Petrosky. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 242-54. Greene, P. (2015). Why critical thinking won’t be on the test. Curmudgucation. http://curmudgucation.blogspot.com/2015/03/why-critical-thinking-wont-be-on-test.html Gruenert, S., & Whitaker, T. (2015). School culture rewired: How to define, assess, and transform it. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development. Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. New York: Teachers College Press. IMACS staff writer (2013). Undoing the damage of standardized testing. Institute For Mathematics & Computer Science. http://www.eimacs.com/blog/2013/04/undoing-the-damange-of-standardizedtesting/ Jacob, E. (1999). The cultural inquiry process. Retrieved from http://cehdclass.edu/cip/ Klemm, W. R. (2011). Teaching children to think: Your kid can be smarter than either of you expect. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/memory-medic/201110/teaching-children-think Kreitzberg, A. & Kreitzberg, C. (2015). Critical thinking for the twenty-first century: What it is and why it matters to you. http://www.agilecriticalthinking.com/Portals/0/WhitePapers/Critical%20Thinking%20for%20the%2021st%20C entury%20for%20Website.pdf Marin, L.M. & Halpern, D.F. (2011). Pedagogy for developing critical thinking in adolescents: Explicit instruction produces greatest gains. Thinking Skills and Creativity 6(2011) 1-13. Parker-Pope, T. (2011). School curriculum falls short on bigger lessons. New York Times. Snyder, L. & Snyder, M. (2008). Teaching critical thinking and problem solving skills. The Delta Pi Epsilon Journal, J 50(2) Spr/Summ, 90-99. Villegas, A. M. & Lucas, T. (2007). The culturally responsive teacher. Educational Leadership, 28-33. Yanklowitz, S. (2013). A society with poor critical thinking skills: The case for ‘argument’ in education. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rabbi-shmuly-yanklowitz/a-society-with-poorcriti_b_3754401.html Zwiers, J. (2005). The third language of academic English: Five key mental habits help English language learners acquire the language of school. Educational Leadership, 60-63.