Breaking the No-Pet Rule By Kymberlie Matthews

advertisement

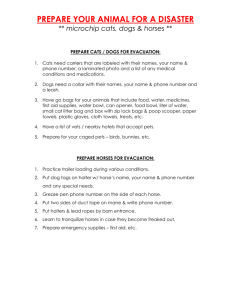

Breaking the No-Pet Rule By Kymberlie Matthews-Adams Most colleges maintain a no-pet rule essentially stating that “for reasons of health, sanitation and noise concerns, pets of any type may not be kept in the residential areas with the exception of fish in proper aquarium facilities (capacity of 10 gallons or less).” Presumably students accept the regulation when they sign their housing contract. They also receive a booklet outlining residence hall policies and the rationale for those policies when they initially move in. Yet it is a guarantee that a number of students violate this simple residence hall policy every year by harboring unauthorized and illegal companion animals in their dorm rooms and apartments. Perhaps the violations stem from the simple pleasure of human/animal interactions. The benefits of human/animal relationships are limitless. Companion animals are found to relieve stress, provide companionship, encourage social interaction, and allow a sense of family which are reassurances that many students seek. However, pet-policy violators cause thousands of animals each year to suffer from malnutrition, disease, abuse, neglect, and eventually abandonment. Dogs, cats, ducks, ferrets, birds, sugar gliders, hedgehogs, mice, rats, chinchillas, lemurs, snakes, squirrels, and hamsters are just a few of the animals that pine for a way out. (See “Pocket Pets,” Spring 2001.) Illegally harbored “dorm pets” often spend hours, even days, locked in closets, boxed, or secured under the bed while students are in class, out socializing, or away for the weekend. Isolated in darkness, dorm pets are sentenced to a stressful, constrained existence with little or no chance to behave naturally. As a result they exhibit stereotypic behaviors, such as pacing, hiding and biting, often becoming a threat to the safety of students. On a limited budget, most students cannot afford their own lifestyles let alone caring for a companion animal. Dorm-pet violators can rarely provide suitable veterinary care or the proper dietary food required for their animal. Dorm pets are fed table scraps, junk food, or any available items including garbage. A poor diet often leads to malnutrition and numerable related diseases. Many dorm-pets also suffer from untreated broken limbs, cuts, sores and bruises. When winter recess or summer break liberates the student population, many dorm-pet violators find themselves inconvenienced. Mom and Dad won’t be pleased to see them walking into the house with an unexpected guest of a different phylum. Many students deem that they have no option but to abandon their seasonal pals. “Before people adopt their pets, they really need to think about what they’re going to do with them as Christmas comes, when the summer comes and when they graduate,” says Jennifer Gentry, president and founder of Aggies Animal Welfare and Rights Ethics (AWARE), Bryon College. Days, weeks go by before the college janitorial staff begins cleaning the dorm rooms. Among discarded notebooks, soiled sheets, ripped posters and heaps of dirty clothes the remains of a lizard is found. An emaciated dog cowers in the closet only to be taken away by animal control. Tanks of algae and rotting fish decorate a barren desk. And under the bed curls the body of a cat that died of dehydration four days ago. “It is so sad, you never know what you will find,” says Ira Lang, janitor at the State University of New York. “We count on finding animals left behind. We just don’t know what to do with the ones still alive. I have four cats that I rescued from here.” Other dorm pets are released into the wild to fend for themselves. Not neutered or spayed, feral animals begin to breed. Overpopulated colonies are not new to campus towns. The animal shelter soon becomes the residence for many pets abandoned by students who took everything home but their animals. Concerned citizens and landlords will walk through the animal shelter doors and present the receptionist with a “pet” which, it seems, was too much of a bother to take home. What once was a novel idea -a snake for a mascot, a dog for show-and-tell - turns into a calamity. Although humane societies, animal control, and certain university staff are becoming aware of the increasing problem with dorm pets, no conclusive data are available. Without statistical evidence it is difficult to surmise the extent of the problem. We do know that most unwanted dorm pets will not find another home. In fact their chances of dying from disease, starvation, or under the wheels of an automobile are much greater. “Neglect or abandonment of a companion animal is against the law in most states,” says API Government Affairs Coordinator Nicole Paquette, “variously punishable by jail time, steep fines, and psychological counseling.” Unwanted dorm pets are often dumped or abandoned outside. There, they risk disease, injury, and starvation. “Outdoor cats, for instance, live an average of 3-5 years, compared to 15-18 years for an indoor cat,” says veterinarian and API Companion Animal Coordinator Jean Hofve. Abandoned animals may be picked up for quick sale to research labs, biological supply companies, or dog fighters looking for cheap live “bait.” Because students rarely have the money to spay or neuter dorm pets, the animals that do somehow survive will contribute more litters to the terrible overpopulation problem that sends more than eight million unwanted dogs and cats to their deaths in shelters every year. There is an absolute lack of regulation when it comes to housing animals in dorm rooms. Insufficient penalties make the possibility of concealing dorm-pets much more appealing to students. Discovered, however, and the pet policy usually means a warning from the Department of Housing for the first violation. When a student blatantly violates the policy for a second time he or she can have the case heard by either a staff member or a school judicial board. That still may not be enough. Barbara Keionig, founder of Home for All Animals (HAA), a small sanctuary that provides homes for strays stated that, “Violators are spoiled and immature. They should be forced to volunteer at an animal shelter to see what life is like for abandoned animals.” An article in The Orion, the college paper at California State University of Chico, tells how two former students decided the fate of their cat Hooter, who became an abandoned, starving alley cat. “Hooter’s owners never took care of him,” said Robert Pence, a resident at the campus apartment complex where Hooter’s owners used to live. “I could always hear Hooter whining for food. His owners tried to get rid of him by dropping him off the side of the road somewhere but the cat came back.” Pence said that he didn’t think Hooter ever saw a veterinarian, because the cat had sores all over his body and was practically a skeleton. “Honestly, I think they were abusive to Hooter,” Pence said. “I remember hearing a couple stories about Hooter. One time they threw him in the freezer, and they used to lower him up and down a two-story balcony. They used to blow marijuana in his face.” Hooter did stay in the apartment occasionally when he was a kitten, but he was kicked outside when his owners became angry with him for not using the litter box they only occasionally changed, Pence said. The spring semester ended, and summer time came, which was good for Hooter since he had spent many cold nights outside. However, Hooter was left to fend for himself. “Everyone who lives here can find Hooter either under a car or on top of its hood,” Pence said. Unfortunately, Hooter’s story is not so far-fetched when college towns are notorious for the feral cat colonies caused by students abandoning their four-footed college “buddies.” Until students learn that they are responsible for the lives they bring with them, Hooter’s tragic story will remain typical of what the average dorm pet can expect.