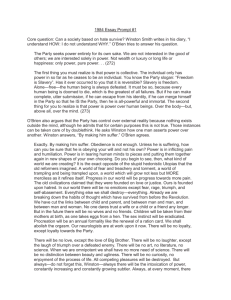

TTTC: Exemplar Passage Commentary

advertisement

Commentary on TTTC Passage: (p. 77-78):"After a firefight, there is always the immense pleasure of aliveness. The trees are alive. The grass, the soil - everything. All around you things are purely living, and you among them, and the aliveness makes you tremble. You feel an intense, out-of-the-skin awareness of your living self - your truest self, the human you want to be and then become by the force of wanting it. In the midst of evil you want to be a good man. You want decency. You want justice and courtesy and human concord, things you never knew you wanted. There is a kind of largeness to it, a kind of godliness. Though it's odd, you're never more alive than when you're almost dead. You recognize what's valuable. Freshly, as if for the first time, you love what's best in yourself and in the world, all that might be light. At the hour of dusk, you sit at your foxhole and look out on a wide river turning pinkish red, and at the mountains beyond, and although in the morning you must cross the river and go into the mountains and do terrible things and maybe die, even so, you find yourself studying the fine colours on the river, you feel wonder and awe at the setting of the sun, and you are filled with a hard, aching love for how the world could be and always should be, but now is not. Mitchell Sanders was right. For the common soldier, at least, war has the feel - the spiritual texture - of a great ghostly fog, thick and permanent. There is no clarity. Everything swirls. The old rules are long longer binding, the old truths no longer true. Right spills over into wrong. Order into anarchy, civility into savagery. The vapors suck you in. You can't tell where you are, or why you're there, and the only uncertainty is overwhelming ambiguity. In a war, you lose your sense of the definite, hence your sense of truth itself, and therefore it's safe to say that in a true war story, nothing is ever absolutely true." Vibrant opposites clash in a war story to effectively portray the chaos and dynamism of the experiences. In this section of The Things They Carried, Tim O'Brien articulates a philosophical scene in which he himself considers the overwhelming ambiguity that war offers. He uses powerful paradoxes and juxtapositions to evoke the contradictions of war: the diverse minds, the ironic rules, and the violently opposing morals. His delicate symbolism assists these contradictions to paint a scene rich with conflict and uncertainty. By opening the section with a balanced sentence, "After a firefight, there is always an immense pleasure of aliveness", O'Brien sets the tone for the passage as a balance of chaos. He neatly places the two concepts -of a firefight, which associates with death, and the 'aliveness' together to form the first juxtaposition. He leads on with the concept of life, depicting symbols of vitality, such as 'grass' and 'trees', where "the aliveness makes you tremble", which appears starkly displaced in the center of the story rich with death and violence, thus offering themselves to the building conflicts. O'Brien reaches into the heart of the men, then, and exposes the contrast between their internal desires, and the external situation. "In the midst of evil you want to be a good man" lends itself to this pattern. By taking hold of his own staggeringly peaceful desires, in which he wants "to be a good man", and holding them up against the violent circumstance, another juxtaposition is crafted. The line, "You want decency. You want justice and courtesy and human concord..." allows their yearnings to clash with their experiences, where morality appears to have been thrust aside in the passion and fear of death. O'Brien employs paradoxes, as well, to loan another angle on the chaotic ambiguity of the war. "Though it's odd, you're never more alive than when you're almost dead." O'Brien operates nature as a vehicle for the final juxtapositions. Serenity is brought out in peaceful scenery, which is present despite the polluted disorder taking place at the same time, perhaps just hours or kilometers away. You "look out on a wide river turning pinkish red, and the mountains beyond, and although in the morning you must cross the river and go into the mountains and do terrible things and maybe die, even so, you find yourself studying the fine colors on the river, you feel wonder and awe at the setting of the sun..." Fog is manipulated as a symbol of war, a lingering, eerie image that evokes its fearful presence. "Thick and permanent. There is no clarity. Everything swirls." This symbol of fog then adopts the position of a pool, of a sort, in the following phrases, in which O'Brien pours a series of juxtapositions, as liquid, untouchable, and powerfully contradictory as the war itself. "Right spills over into wrong. Order blends into chaos, love into hate, ugliness into beauty, law into anarchy, civility into savagery." They are the streams of emotions soldiers find most ambiguous, as the violence and destruction of the war melts each morality into a theory with no laws, and mirrors the narrative stream of conciousness that O'Brien employs throughout the entire novel "You lose your sense of definite, hence your sense of truth itself." The paradoxes "the only certainty is overwhelming ambiguity" and "in a true war story nothing is ever absolutely true" are finishing touches on the final completion of the vigorous opposites which have been carefully constructed together to balance one another in this piece of ordered chaos. As O'Brien has explored the power that opposites, when carefully composed adjacent to one another, offer. He sheds light on the presence of such conflict and opposition in life, as we know it. The ways our minds and thoughts contrast with our environments and experiences perhaps convey our emotions as they are. If every element of life were in sync and compatible, there would be no inspiration, no signals nor change, no diversity, no pleasure nor suffering. These vivid oppositions, in many ways, appear to supply us with our humanity and development.