Miranda Schmidt Sociology 230 Japanese Internment Through the

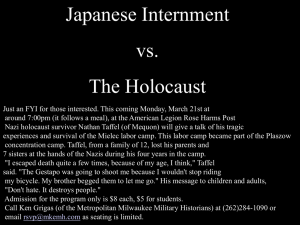

advertisement

Miranda Schmidt Sociology 230 Japanese Internment Through the development of the United States as it stands today, immigrant minority groups have been subjected to different forms of prejudice, racism, and discrimination; the Issei or first generation Japanese immigrants were not excluded nor would their children, Nisei, be (Preservation Idaho). In fact, over 100 years after the first immigrants migrated to what they considered a place of economic opportunity, and had certified their status of Japanese Americans, they would experience such devastating discrimination and prejudice that it would eventually lead to forcible removal, “from designated military areas [their homes] along the Pacific Coast between the latter part of 1942,” (Sharp). As America moved closer to the fateful day December 1941, which would be known as the cause of the Second World War, Japanese Americas were known to experience discrimination, and prejudice. The racism they experienced from fellow Americans ranged from verbal slurs, limited access to jobs and even at times property debasement. But nothing would compare to what followed the winter of 1941 (Speidel). On December 7th, 1941, at the sight of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, Japanese bombers, killed over 2,500 individuals, a caused President Franklin D. Roosevelt to declare a war he had attempted to avoid, the very next day (Healey 374). At this time, President Roosevelt choose to ignore a secretly commissioned report by Curtis Munson regarding Japanese Americans, that stated, “There will be no armed uprising,” for, “the local Japanese are loyal to the United States,” and signed Executive Order 9066 (Takaki 386). Executive Order 9066, “gave the secretary of war and military commanders the authority to prescribe military areas in such places and of such extent…which any or all persons may be excluded,” meaning they had the power to remove Japanese families from their homes and place them within internment camps (Sharp). Throughout the United States, the government had built ten permanent detention camps, sixteen temporary detention centers, and twenty-seven Justice Department internment camps that would hold over 120,000 Japanese Americans from of span of 1942 to 1945 (Educational Resources). Within the state of Idaho, which held both a detention camp in Minidoka as well as a Justice Department camp in Kooskia, more than 9000 “prisoners” would be housed there for approximately 3 years. These “prisoners” were not all native Idahoan’s, in actuality a majority of the individuals were from the regions of Seattle, Pierce County, Washington, Portland and Northwestern Oregon, (Educational Resources). Although Japanese Americans were not taken en masse they were not given a choice when it came to relocation and they were rarely given time to pack up all of their belongings. Actually, they were instructed by armed soldiers to only take what they could carry- clothes, kitchen items, linens, toiletry items, and mementos, and given no time to get their other affairs in order before they were transported to holding areas, that were unsanitary and overcrowded (Sharp). From there they would be shipped to the various camps. For those whom were transported to Minidoka, known as Hunt Camp, they found poorly constructed buildings, barracks, schools, stations, and even cemeteries (History). These building possessed no insulation and were ill-suited for the extreme temperatures within Idaho. Not to mention, the entire camp was surrounded with barbed wire fencing, and guard towers to watch over “prisoners” (Minidoka National Historic Site). Yet within the camps, prisoners continued to be fiercely loyal to the United States and volunteered to serve their country. In fact, 10% of those interned at Minidoka would enter military service, many even serving with the “famed 442nd Regimental Combat Unit, which saw extensive action in France and Italy and was the most decorated unit of its size and length of service,” (History). As for the Justice Internment Camp placed in Kooskia, Idaho, over 250 detainees were held (Geranios). In contrast to permanent internment camps, Justice Department sanctioned camps, “ were used to incarcerate,” what America deemed as dangerous Japanese living in America to possible use as bargaining chips in the war (Education Resources). However many were never used and none were ever convicted of treason. Nonetheless, “prisoners” within the camp, were the first to be used as a labor crew they were put to work, “doing road [construction] on highway 12,” through the mountains of Idaho (Geranios). Because these detainees were put to work and were paid for their work detainees in other camps attempted to be moved so they would be able to make money during this terrible time (Geranios). What is most evident through the recounts from prisoners and soldiers is they were trying to make a home for them and their children at the time of internment and fortify a future for themselves after being released while suffering such discrimination, racism and prejudice. As time passed and World War II was raging on Japanese Americans continued to survive within the camps, by keeping busy through being doctors, teachers, and cooks. They would send their kids to the make shift schools, and would garden and attempt to have some semblance of the life they held with the addition of being guarded by men with guns. But soon after the United States dropped the atomic bombs on Japan, Japan signed a surrender ending the ward that incarcerated them (Calisphere). With the war drawing to an end, Japanese Americans were beginning to be released from their internment camps and in Minidoka, Idaho on October 28, 1945 the camp was closed and they were allowed to return home (Education Resources). However they were met with hatred by those around them wishing that they would never be allowed to return home. Many anti- Japanese groups sprung up and would viciously combat Japanese Americans within their homes however; they were not successful in driving them away. However it would not be until June of 1952, until Congress passed the McCarran Walter Act, allowing Japanese aliens to have the rights of citizen and it would not be until 1976 under the power of President Ford, that the Executive Order would be rescinded (Calisphere). References Geranios, Nicholas K. "Kooskia Internment Camp Discovered In Mountains Of Idaho." The Huffington Post. Huffington Post, 27 July 2013. Web. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/07/27/kooskiainternment-camp_n_3663446.html>. Healey, Joseph F. "Chapter 9: Asian Americans." Race, Ethnicity, Gender, and Class: The Sociology of Group Conflict and Change. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2012. 361-401. Print. "History." Preservation Idaho. The Idaho Historic Preservation Council, n.d. Web. <http://www.preservationidaho.org/advocacy/minidoka/history>. "List of Internment and Detention Camps." Education Resources. CLPEF Network, n.d. Web. <http://www.momomedia.com/CLPEF/camps.html>. "Minidoka National Historic Site." Preservation Idaho. The Idaho Historic Preservation Council, n.d. Web. <http://www.preservationidaho.org/advocacy/minidoka>. "Relocation and Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II."Calisphere. University of California Libraries, n.d. Web. <http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/jarda/historicalcontext.html>. Sharp, Rebecca K. "How An Eagle Feels When His Wings Are Clipped and Caged." Prologue Winter 2009: n. pag. Print. Speidel, Jennifer. "Anti-Japanese Organizations." After Internment Japanese American's Right to Return. University of Washington, n.d. Web. <http://depts.washington.edu/civilr/after_internment.htm>. Takaki, Ronald T. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. Boston: Little, Brown, 1998. Print.