physician compare

September 8, 2015

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

Acting Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

Department of Health and Human Services

Attention: CMS-1631-P

Submitted electronically to: http://www.regulations.gov

Re: CMS-1631-P, Medicare Program; CY 2016 Revisions to Payment Policies under the

Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Medicare Part B.

Dear Mr. Slavitt:

On behalf of the Premier healthcare alliance serving approximately 3,600 leading hospitals and health systems and 120,000 other providers, we appreciate the opportunity to comment on the

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) calendar year (CY) 2016 physician fee schedule proposed rule. Premier healthcare alliance, a 2006 Malcolm Baldrige National Quality

Award recipient, maintains the nation's most comprehensive repository of hospital clinical, financial and operational information and operates one of the leading healthcare purchasing networks. Our comments primarily reflect the concerns of our owner hospitals and health systems that not only employ physicians, but also operate accountable care organizations.

Premier runs one the largest population health collaboratives in the country, the Partnership for

Care Transformation (PACT™). In addition, Premier is also currently serving as a qualified clinical data registry (QCDR) and qualified registry under the Medicare Physician Quality

Reporting System (PQRS).

MEDICARE SHARED SAVINGS PROGRAM

We appreciate that CMS continues to use the National Quality Strategy as its framework across measurement programs and emphasize outcomes measures for high-impact conditions.

Furthermore, we support CMS’ continued efforts to align the Medicare Shared Savings Program

(MSSP) with the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS); however, we are concerned that

CMS is not making similar efforts with the Inpatient or Outpatient Quality Reporting Programs.

Hospitals are integral components of ACOs, even if they are not the conveners, and represent a

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 2 of 19 large portion of both the care provided and spending incurred. We urge CMS to align the hospital quality reporting programs with the MSSP.

New Measure

CMS proposes to add one measure, S tatin Therapy for the Prevention and Treatment of

Cardiovascular Disease, which will account for two points in the preventive health domain. The measure assesses the percentage of beneficiaries who were prescribed or were already on statin medication therapy during the measurement year and who fall into any of the following three categories:

Patients 21 or older who were previously diagnosed with or currently have an active diagnosis of clinical atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD);

Patients 21 or older with any fasting or direct Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

(LDL-C) level that is greater than or equal to 190 mg/dL; or

Patients 40 to 75 with a diagnosis of diabetes and a fasting or direct LDL-C level of 70 to

189 mg/dL.

It is difficult to comment on the value of this measure in the absence of full measure specifications. However, we have concerns with last two of the proposed denominators – patients

21 or over with an LDL-C greater than 190 and patients 20-75 with diabetes and a fasting LDL of 70-189. For both denominators, it is unclear on what date the LDL-C level needs to occur to place individuals in the denominator population. It is also unclear whether or not the LDL-C check should happen prior to the patient starting lipid lowering therapy. The most recent guidelines do not recommend testing LDL-C, but rather recommend starting statins for elevated cardiovascular risk. Therefore, many patients may not have any or a current LDL-C level documented, resulting in a small denominator population. Finally, the third denominator does not align with the current clinical guidelines which recommend initiating statin therapy for all patients with diabetes who are age 40-75. The guideline does not specify a LDL-C level for this population, yet the measure restricts the population to those with an LDL-C level of 70-189; this variation may result in a smaller denominator population that does not reflect total care. While the Premier healthcare alliance appreciates CMS’ efforts to address cardiovascular disease and develop measures that better align with current clinical guidelines, field testing results are not available and the measure is not NQF-endorsed. Accordingly, we do not support the addition of the Statin Therapy measure at this time and request that CMS address the issues we raise through the NQF-endorsement process.

CMS also seeks comments on how to implement and weight the measure; weighting the three denominators equally when calculating the performance rate, the number of points to assign for reporting and benchmarking, the size of the oversample, and the pay-for-performance status. As noted earlier, it is difficult to comment on the best approach for implementing the measure in the

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 3 of 19 absence of specifications and testing results. For example, if one of the denominators accounts for the majority of the patient population, it would not be appropriate to equally weight the denominators. Similarly, population size, performance range and performance gap should be considered when determining scoring. If one of the three denominators has a relatively small performance range and performance gap, but is not yet topped out, then scoring should remain at

2 points for all three measures. If all three denominators have large populations with varying performance and room to improve, it may be appropriate to individually score each denominator and assign 1 point to recognize that various performance strategies are needed to address each of the denominator populations.

While we do not support the addition of the Statin measures, if CMS choses to do so, it should remain as pay for reporting for all three years. There are too many unknowns about the measure. This will allow sufficient time for ACOs and CMS to gain experience with the measure and provide opportunity for measure specification revisions without impacting performance.

Measures that No Longer Meet Clinical Guidelines

CMS is proposing a new policy in which measures will remain as pay-for-reporting or revert from pay-for-performance to pay-for-reporting when the measure owner determines the measure no longer meets best clinical practices due to clinical guideline updates or clinical evidence suggests that continued measure compliance and collection of the data may result in harm to patients. Changes would be finalized in the subsequent physician fee schedule rule with comment period.

We appreciate that CMS is proposing a policy to address measures that no longer align with clinical guidelines; however, we believe measures should be suspended rather than continue to be reported. In its description of this policy CMS states “continued measure compliance and collection of data may result in harm to patients.” If collection of data may cause harm to patients, all data collection efforts should cease. Continued reporting requires ACOs and their providers to devote efforts to tracking information that is no longer recommended or may cause beneficiary harm. Moreover, with continued reporting the measure will be incorporated into the value-modifier determination for eligible professionals billing under the TIN of an ACO. Thus, continued reporting will encourage provider monitoring and quality improvement for a measure that may cause patient harm. A policy in which measures that no longer meet clinical guidelines are suspended would align with policies for other CMS quality and payment programs, such as the Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting Program and the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting

Program. We agree that final changes should be finalized in subsequent rulemaking; however, if a measure no longer aligns with clinical guidelines, we do not support

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 4 of 19 maintaining measures as pay-for-reporting and recommend that the measure be immediately suspended through subregulatory guidance.

Use of Health Information Technology

Currently, CMS assesses adoption of health information technology (IT) with the measure

Percent of PCPs who Successfully Meet Meaningful Use Requirements . CMS seeks comments on how to evolve the assessment of health IT adoption and ensure that they are rewarding and incentivizing health IT adoption. Specifically, CMS seeks input on application of the existing measure to all eligible professionals, rewarding providers who achieve higher levels of health IT adoption, and other measures that focus on the use of health IT or IT-enabled processes. The

Premier healthcare alliance supports CMS’ efforts to continually encourage the adoption of health IT. We believe CMS’ efforts in this area should focus on development of electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs) and promoting an interoperable health IT infrastructure . Many eCQMs available for reporting are measures that were originally claims or chart-abstracted measures and later re-specified as an eCQM. CMS should devote effort to de novo eCQMs that are developed in the context of EHR workflows and assess the use of ITenabled processes. For example, communication between settings and outcomes assessed longitudinally across settings should be explored for development of eCQMs. Another option for measuring IT-enabled processes could be through assessing the interoperability capabilities of

EHRs. For example, a measure assessing whether an EHR successfully transmits transition information to receiving facilities in a timely manner could serve as a balance to potential eCQMs that assess providers on communication between settings. As Premier noted in our comment letter on Stage 3 of the electronic health record (EHR) meaningful use program, HIT systems that do not allow for open exchange and lock data in proprietary systems create enormous obstacles for providers to make the best use of HIT in the delivery of care. The interoperability issues should be addressed prior to adopting additional requirements for ACOs and providers.

Beneficiary Assignment

CMS assigns beneficiaries to an ACO based on their utilization of primary care services. CMS proposes changes to the method for assigning beneficiaries by excluding evaluation and management services (CPT codes 99304-99318) in skilled nursing facilities (SNF) when the claim includes a modifier that the place of service is a SNF (POS 31). The evaluation and management codes will continue to be included if the modifier indicates the place of service is a nursing facility (POS 32). CMS indicated that beneficiaries in a SNF are receiving short-term post-acute care and these services cannot be considered primary care services. We agree that the evaluation and management services received by beneficiaries during the immediate post-acute care period is not indicative of primary care and should not be used in the ACO attribution

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 5 of 19 process. Additionally, for electing teaching hospitals CMS proposes to use HCPCS code G0463 in lieu of CPT codes (99201-99205 and 99211- 99215) to align with a change made in the CY

2014 Outpatient Hospital Prospective Payment System final rule. This was an unintended consequence of a completely unrelated policy change. We support the proposed changes to the assignment of beneficiaries.

COMPREHENSIVE PRIMARY CARE INITIATIVE

The Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC) Initiative is a multi-payer initiative in which practices receive a monthly non-visit-based care management fee for each Medicare FFS beneficiary and, in cases where the state Medicaid agency is participating, for each Medicaid FFS beneficiary.

The Premier healthcare alliance appreciates that CMS continues to explore new payment models through the Innovation Center. While we believe the CPC initiative promotes comprehensive care management, CMS should consider how this effort overlaps with other payment programs and Innovation Center models when determining whether and how to expand the program. For example, some ACOs have encountered difficulty recruiting primary care physicians in markets where many physicians participate in the CPC initiative as providers would prefer the care management payment up front in lieu of receiving shared savings later. Incorporating the CPC concepts into MSSP, rather than on their own, would support aligned incentives and might lead to enhanced results.

CMS should consider how to combine CPC with models such as bundled payments and ACOs.

For example, some innovative ACOs incorporate bundled payments and care management payments in their overall payment model, ensuring alignment across multiple provider types and settings, but with a goal of reducing total spending and improving overall care. We suggest

CMS test such a layered model to determine if the synergies between the programs results in better overall outcomes for beneficiaries and Medicare.

Finally, we believe CMS should consider how the CPC initiative can incorporate nominal financial risk if CMS expands the model. All revisions and expansions to the current Innovation

Center models should meet the requirements of an eligible alternative payment program (APM) as providers will want to choose from a breadth of eligible APMs when MACRA is implemented.

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 6 of 19

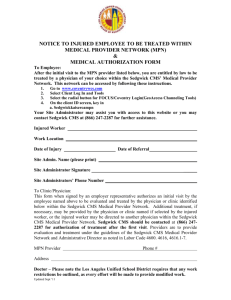

PHYSICIAN COMPARE

Additional Data on Physician Compare

The proposed rule continues to expand the information available on Physician Compare and in the accompanying downloadable dataset. On the Physician Compare website, CMS proposes to add: an indicator for receiving an upward adjustment from the value-based payment modifier

(VM), an indicator for those who choose to report measures that support HHS’ Million Hearts initiative, patient experience (CAHPS) results for groups of two or more who report through the

GPRO Web interface, and two additional board certifications. CMS also proposes additions to the downloadable database: value-modifier quality tiers for cost and quality, value-modifier payment adjustment received, indication of eligible professionals who did not report quality measures but were eligible to participate, and utilization data generated from Part B claims.

Additionally, CMS proposes to continue to provide performance rates, including CAHPS for those required to report – eligible professionals who bill under ACOs in Shared Savings, groups, and individual eligible professionals across all reporting options.

We support CMS’ proposals to enhance transparency by adding additional information to Physician Compare and the accompanying downloadable database.

CMS also seeks comments on potential future additions to Physician Compare, including additional measure concepts to add to Physician Compare, Medicare Advantage health plans accepted by the eligible professional, downward or neutral value-modifier adjustments, open payments data, and stratification of results by race, ethnicity and gender. Premier appreciates

CMS’ efforts to continually enhance transparency of information provided; however, public reporting should be expanded slowly to ensure that the information available can be understood by consumers and is meaningful to consumer choice. CMS should more readily add information to the downloadable database so that interested stakeholders have the opportunity to analyze and use the information in their quality improvement efforts.

Additionally, making the information available in the downloadable database will foster more informed public comment on the value additional information to consumers.

Benchmarking

CMS proposes to post an item-level benchmark the year following the performance period for several reporting options – PQRS GPRO and individual reporting through a registry, EHR and claims. CMS proposes to use the Achievable Benchmark of Care™, which is the average performance of the top providers that account for 10 percent of the patient population.

Specifically, this method rank orders physicians or groups, identifies the top performers that account for 10 percent of the patient population, and then determines the average score for the

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 7 of 19 selected patient population. The methodology includes considerations for low denominators and would only be applied to measures deemed valid and reliable. CMS also indicates that this method will be used to assign stars for the Physician Compare five-star rating; however, the methodology is not described in the rule.

The Premier healthcare alliance appreciates CMS’ efforts to provide benchmarks, providing context for provider performance rates; however, we have some concerns about this approach for benchmarking. The proposed methodology assigns a benchmark based on 10 percent of beneficiaries served by the top performers. Depending on variation in a measure, this may be the

95 th

percentile of all providers (in a measure with wide variation) or the 30 th

percentile (in a measure with little variation). Moreover, the benchmark may vary widely each year because the number of beneficiaries and providers contributing to the benchmark can change significantly since providers can choose a different set of measures to report each year. Similarly, providers are only required to report performance for 50 percent of their population, but have the option to report more information. This introduces additional variability that can impact the benchmark.

Also, we are concerned that the performance for the top 10 percent of beneficiaries may not be achievable for all beneficiaries given the limited risk adjustment in many measures. CMS should consider using the top 25 percent of beneficiaries served by the top performers to mitigate the impact of measure variation.

While the proposed rule indicates that there will be separate benchmarks for groups and individual clinicians, CMS should consider developing benchmarks for each reporting option.

For example, small group practices of two to nine physicians and large group practices of 100 or more physicians will be compared to one another if they report the same measure. This places small group practices at a disadvantage as they have less experience reporting performance measures (as large groups were required to participate in PQRS before small groups) and tend to have fewer resources to devote to quality improvement. Moreover, while they may meet the measure minimums, they may still experience higher variability in their performance results as a result of lower volume. Similarly, measures reported through the GPRO Web interface should not be compared to measures reported through claims or registries as the GPRO Web interface reporting option includes sampling methodology that is different than the other reporting options.

Additionally, CMS is proposing to separately benchmark eCQMs for the value-modifier, recognizing that eCQM specifications may differ from the specifications for other reporting mechanisms. A similar approach should be used when providing benchmarks on Physician

Compare. CMS should explore how the different reporting options contribute to variation in performance prior to benchmarking.

The proposed methodology may not be appropriate for all measures; specifically, utilization or appropriateness measures that do not have a clear indication of optimal performance (e.g., ambulatory sensitive conditions where lower is better, but 0 is not possible), measures that are

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 8 of 19 based on a comparison to average performance (e.g., readmission measures, episode-groupers,

Medicare Spending per Beneficiary), and measures with significant regional variation. With these types of measures, the achievable benchmark would have a different interpretation for each measure that would not be evident to beneficiaries viewing performance results on Physician

Compare. Such measures are better suited for benchmarks that consider standard deviations above or below the mean.

Finally, the implementation of MIPS for CY 2019 payment (likely CY 2017 performance) will significantly shift the types of information available to consumers on Physician Compare. For example, it may be more reasonable to report a provider’s total MIPS score rather than individual performance rates and benchmarks for each measure. Beneficiaries would not benefit from having one set of benchmarks for one calendar year only to have the methodology switch the following year. Premier suggests that CMS delay benchmark reporting and consider benchmarks in the context of the most appropriate information to report on Physician

Compare for MIPS. Furthermore, in considering benchmarking approaches, CMS should explore methods used in other reporting programs, such as comparison to average performance

(i.e., lower, higher, no difference).

QCDR Measure Reporting

In addition to publicly reporting all individual level QCDR PQRS and non-PQRS measures,

CMS proposes to publicly report group level QCDR PQRS and non-PQRS measure data on

Physician Compare. During self-nomination the QCDR would be required to declare if it will provide data to CMS for reporting on Physician Compare or if it will post data on its own website and allow Physician Compare to link to the website. We continue to be worried about the multitude of measures that may be very similar, but sufficiently different to prevent comparison by beneficiaries. For instance, our readmission methodology is different than the allcondition PQRS readmissions measure. If beneficiaries see on Physician Compare one measure result for one doctor next to another measure result for another doctor, they may assume they are comparable when in fact they are not. As discussed in greater detail below, we support the expansion of QCDRs to physician groups and appreciate the flexibility in allowing QCDRs to publicly report via their own website or Physician Compare.

PHYSICIAN QUALITY REPORTING SYSTEM

Collection of Additional Data to Support Stratification

CMS states that it intends to report data by race, ethnicity, primary language and disability status; in the future, CMS will propose to require this information be collected in each PQRS reporting mechanism. CMS notes that they will plan a phased approach, possibly beginning with

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 9 of 19 a subset of measures. Accordingly, CMS seeks comment on the facilitators and obstacles to collecting and reporting these additional data elements. While we appreciate CMS’ effort to incorporate demographic factors into measurement and reporting, we caution that stratification may not be the best approach for all measures as risk-adjustment is better for some measures.

When publicly displaying measures and using them to reward and penalize a provider, we must consider the context within which providers are working. We strongly believe that every patient who enters the door of a provider facility should expect the same outcome; however, it is also important to understand the increase or decrease in outcome risks associated with sociodemographic factors that are outside of the control of the provider. Use of these factors in risk adjustment allows for fair cross-provider comparisons and does not penalize one provider over another or convey one provider is lower quality simply due to their willingness to treat any patient, despite that patient having an increased risk in poor outcomes due to endogenous factors that are captured in proxy measures such as socidemographic variables. This can create a perverse cycle, wherein we deny resources (both payment penalties and income by discouraging beneficiaries from using these providers) to providers that care for such patients, subsequently leading to unequal care for those patients due to lack of equal resources to treat them.

Additionally, measures reported through a QCDR may already have risk-adjustment methodologies that include multiple socio-demographic factors; it would be inappropriate to stratify measures that have already been risk-adjusted.

Finally, individual and small group reporting stratification will likely result in small denominators that should not be publicly reported. Stratification may lend itself best to aggregate reporting that could be used for research purposes and continued refinement of the measures.

Premier recommends determining if there is value in stratification at the individual measure level, and a concerted effort on CMS’ part to encourage the adoption of measures in PQRS that are risk-adjusted for socio-demographics.

While preferred language, race and ethnicity are part of the Meaningful Use requirements, the threshold for meeting the requirement is only 50 percent of all patients for stage 1 and 80 percent of all patients for stage 2. Even when meeting the meaningful use requirements, EHRs capture this information in highly variable formats. While providers reporting eCQMs and QCDRs who choose to report demographic information would be a reasonable start for the collection of demographic information, CMS will likely face challenges with data consistency. Providers who have not achieved meaningful use may not document this demographic information or it is documented in a format that cannot be readily reported. Implementing this requirement may place undue burden on providers whose efforts would be better spent on achieving meaningful use. CMS should field test the collection of demographic information in each reporting mechanism before implementing a requirement.

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 10 of 19

Proposed Changes to the Requirements for the QCDR

CMS proposes multiple changes to the requirements for entities to be considered a QCDR. First,

CMS proposes to open the self-nomination period earlier, beginning on December 31 of the prior year instead of January 1 of the certification year. We appreciate CMS’ efforts to provide entities additional time so submit a self-nomination statement. Next, CMS proposes to shorten the establishment requirement for QCDRs, requiring that an entity be in existence by January 1 of the collection year instead of January 1 of the year prior to the collection year. While we appreciate CMS’ flexibility, we believe that using untested QCDRs places providers at risk. If a newly formed QCDR encounters any technical difficulties or fails data validation, providers will be unable to report PQRS data and will incur penalties. In lieu of changing the existing establishment requirement, we propose that CMS explore options for making other aspects of the eligibility criteria more flexible. For example, it may be appropriate to eliminate the establishment criteria if a new QCDR is built on platforms of existing QCDRs; using an existing platform that has successfully submitted QCDR data eliminates the need for establishment requirements.

CMS has also proposed changes to the attestation statements for QCDRs submitting quality measure data. QCDRs would be able to attest to the data submission using a Web-based checkbox mechanism and would have to submit all required information (including measure specifications and the data validation plan) at the time of self-nomination. CMS notes that an entity cannot change any of its information after the submission deadline but will be able to submit supplemental information requested by CMS. In past years the measures and validation strategy were submitted after the prior year’s measure submission; this allowed vendors to make any needed modifications to the measures based on prior performance. Across all quality programs, measures frequently undergo an annual update, making minor modifications that do not substantially change the measure. The proposed change in timeline will not allow an annual update for QCDR measures; this is particularly concerning as ICD-10 implementation is likely to create measurement challenges that can be addressed through an annual updated process. CMS should continue to review measures and the validation strategy after the prior year’s measure submission or CMS should have a process for allowing submission of modifications to the measures and validation plan. Additionally, we request that CMS provide more guidance regarding the validation plans. In the past we have not received feedback on our validation plans and would welcome more guidance up front or feedback after submission.

Finally, to align with the provisions of MACRA, CMS proposes to allow group practices registered to participate in GPRO to submit measures through a QCDR. The proposed reporting period is 12 months. The Premier healthcare alliance applauds CMS for quickly implementing a QCDR option for groups. Similarly, we request that QCDRs are an option for reporting GPRO Web interface measures for groups and ACOs. The GPRO Web

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 11 of 19 interface remains one of the few reporting mechanism that do not allow vendors to report on behalf of the reporting entity. Our MSSP participants and large groups routinely recount difficulties in submitting measures via GPRO Web interface. Allowing vendor submission will not only relieve some burden from providers, but will also increase the accuracy of reporting as vendors can do automated accuracy checks of the data and return it for correction before submission.

Proposed Changes to the Requirements for Qualified Registries

CMS proposes parallel changes to the requirements for entities to be considered a qualified registry to the changes proposed for QCDRs. Specifically, CMS proposes to allow attestation via a Web-based checkbox mechanism and require submission of the validation strategy at the time of self-nomination. We support the proposed changes.

Auditing of Entities Submitting PQRS Quality Measure Data

CMS audits PQRS participants and vendors who submit quality measure data; in order to perform audits CMS requires additional information. CMS proposes that any vendor submitting quality measure data for PQRS must retain all data for at least seven years and provide contact information for each EP for whom it submits data. Premier suggests that CMS allow vendors to submit contact information for the EP or their designee. Frequently, EPs have someone in their practice who is responsible for supporting quality reporting efforts; this information may be more beneficial to CMS.

New Measures

As noted in our discussion of new measures for MSSP, we do not support the addition of the

Statin Therapy measure at this time. The measure should be tested and reviewed for NQF endorsement prior to implementation in the program. When a measure is adopted for MSSP and the GPRO Web interface, the status of the measure should be treated similarly across programs with regard to pay-for-performance or pay-for-reporting status.

That is, if the measure is scored as a pay-for-reporting measure in MSSP, it should be not be included in the value-modifier quality-tiering calculation for providers and groups reporting through the Web interface. Currently, a new measure in PQRS is included in the value-modifier in the first year of implementation while new measures in MSSP are typically considered pay-for-reporting in the initial years. Accordingly, the ACO and the eligible professionals billing under the TIN of an

ACO are held to different standards for the same measure. The ACO process is preferred as it allows eligible providers to get accustomed to submitting the measure and then allows time to establish a benchmark before the measure is used for performance.

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 12 of 19

ECQM AND CERTIFICATION CRITERIA

CMS proposes to revise the certified EHR Technology (CEHRT) definitions that apply to eligible professionals, eligible hospitals and critical access hospitals participating in the EHR incentive programs. For 2015-2017, the CEHRT definition would be would be modified to require that EHR technology be certified to report electronic clinical quality measures (eCQMs), in accordance with the optional portion of the 2015 Edition CQM reporting criterion certification if certifying to the 2015 Edition “CQMs – report” certification criterion. Specifically, this would require technology to be certified to the QRDA Category I and III standards and the optional

CMS “form and manner.” CMS also proposes to continue using this revised CEHRT definition for 2018 and subsequent years. We are concerned about how the revised CEHRT definitions will impact hospital-based physicians who are not required to participate in the EHR incentive program but are required to submit measures for PQRS. The QRDA Category I data does not provide physician information, making it challenging to report eCQMs for hospital-based physicians. CMS should address these challenges in the CEHRT definitions. Additionally,

CEHRT definitions should include standards for interoperability. Reporting eCQMs would be enhanced with improved access to the disparate systems used to track clinical and health data.

Often data are locked behind proprietary systems, posing interoperability challenges for the delivery of care and monitoring of clinical quality.

VALUE-BASED PAYMENT MODIFIER

CMS proposes to expand the value-based payment modifier (VM) to non-physician groups and solo eligible professionals (EPs), physician assistants, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists and clinical nurse anesthetists in CY 2018 (CY 2016 reporting). CMS proposes that non-physician solo practitioners and non-physician EPs in groups consisting of only nonphysician EPs will not have any down-side risk for CY 2018. Additionally, CMS did not propose any changes to the payment adjustment or payment at risk for others participating in the valuemodifier. Accordingly, for EPs (physician and non-physician) in groups with 10 or more EPs, the payment at risk is 4 percent and the maximum upward adjustment is 4.0 times the adjustment factor; for EPs (physician and non-physician) in groups of two to nine EPs and solo physician practices, the payment at risk is 2 percent and the maximum upward adjustment is 2.0 times the adjustment factor; for non-physician EPs and groups that consist of only non-physician EPs, the payment at risk is 2 percent and the maximum upward adjustment is 2.0 times the adjustment factor. With the implementation of MACRA planned for CY 2019 payment (likely 2017 performance), we appreciate CMS’ efforts to maintain the payment at risk for providers currently participating in the value-modifier and align the expansion to non-physician EPs with MACRA requirements for MIPS. Limiting modifications to the existing physician quality and payment programs allows all stakeholders to devote resources to preparing for the implementation of

MIPS and other MACRA provisions. We support the proposed expansion to non-physician

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 13 of 19

EPs and the payment at risk and upward payment adjustments under the quality-tiering methodology.

Group Size

CMS queries PECOS to determine which groups and solo practitioners are subject to the valuemodifier and to determine group size. CMS proposes that group size would be determined based on the lower number of EPs indicated by PECOS or by claims analysis. We appreciate CMS’ flexibility in determining group size.

Quality Measures

Benchmarks for eCQMs

CMS proposes to exclude eCQM measures from the overall benchmark for a measure and create separate eCQM benchmarks. We appreciate that CMS recognizes eCQM specifications and performance is different from the parallel claims, registry or Web interface measures. We believe similar inconsistencies exist between all reporting options and encourage CMS to consider developing benchmarks by reporting method.

MSPB Measure

Currently CMS requires 20 Medicare Spending Per Beneficiary (MSPB) episodes for inclusion in the MSPB measure for a TIN’s cost composite. Due to reliability concerns, CMS proposes to increase the minimum number of episodes to 100. Additionally, CMS proposes to include

Maryland hospital stays as an index admission; these hospital stays were previously excluded because CMS was using a specification for the Hospital IQR program. While we support these proposals, CMS should conduct reliability studies and ensure the specifications are appropriate for the program in advance of implementation.

Application of VM to Pioneer, CPCI, and other Innovation Center Models

CMS is proposing to waive application of the value-modifier for groups and solo practitioners who participated in the Pioneer ACO model, the CPC initiative, or other Innovation Center models that are deemed similar to Pioneer ACOS and CPC initiative. CMS notes that this policy is proposed under the waiver authority of section 1115A(d)(1) and would sunset prior to the implementation of MIPS. Similarly, CMS notes that new Innovation Center models in development, such as Next Generation ACOs, oncology care model and the comprehensive

ESRD care initiative, would be considered similar to the Pioneer ACO or CPC initiative. We support exempting EPs who participate in Pioneer ACOs, CPC initiative and other

Innovation Center models from application of the VM and suggest this proposal is extended to EPs who participate in MSSP.

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 14 of 19

Application of VM to Shared Savings Program

CMS will apply the value-modifier to physicians (groups or solo practitioners) who participate in the MSSP as part of an ACO, beginning with the 2017 payment adjustment. CMS will apply performance rates submitted by the ACO to the physicians under the TIN of the ACO to calculate the quality composite and will consider the physician cost composite to be “average.”

For the 2018 payment adjustment, CMS proposes to expand this approach to non-physician EPs who are part of an ACO that participates in MSSP. Premier does not support continuing the policy to apply the VM to physician and non-physician EPs participating in MSSP.

Section 1848(p)(5) of the Social Security Act states, “the Secretary shall, as appropriate, apply the payment modifier established under this subsection in a manner that promotes systems-based care.” We believe that the MSSP incentives parallel the VM and meet this standard of applying a payment modifier in a manner that promotes system-based care. Arguably, it does so better than the proposed VM. The approach for applying the value-modifier to EPs in MSSP ACOs is counterintuitive to the intent of the value-modifier. With receiving a designation of “average cost,” EPs would never be eligible for the maximum rewards (or penalties) provided under the

VM methodology. Additionally, CMS has developed conflicting policies for the application of quality measures; as we noted earlier, new measures in MSSP are considered pay-for-reporting for the ACO, but for eligible professionals the measure will be incorporated into the quality composite. This misalignment makes it difficult for the ACO and eligible professionals billing under the ACO to be aligned on quality improvement approaches.

We believe this policy complicates the transition to population health and will create confusion with the implementation of MACRA. CMS has recognized that EPs participating in ACOs are different from EPs participating in traditional Medicare fee-for-service as CMS has proposed to exempt EPs participating in other ACOs (Pioneer, Next Generation) from VM. Misaligned policies across ACOs create provider confusion and incentivizes one model over another, despite both Pioneer and MSSP ACO models having proven to be effective. Many EPs participating in an ACO that is part of MSSP will likely be exempt from MIPS and receive a bonus for APM participation, yet they will be subject to value-modifier for two years, while EPs participating in other ACO models will have a more seamless transition to the new payment model.

APPROPRIATE USE CRITERIA

Section 218(b) of the PAMA amended Title XVIII of the Act to add section 1834(q) directing

CMS to establish a program to promote the use of appropriate use criteria (AUC) for advanced diagnostic imaging services. In the proposed rule, CMS seeks comments on implementing

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 15 of 19 certain components of the Medicare AUC program and is proposing to codify and add language to clarify definitions provided in statute.

Applicable Setting

CMS is proposing to define an applicable setting as a physician’s office, hospital outpatient department (including ED) and an ambulatory surgical center. Inpatient hospitals are not considered applicable settings. While we agree with CMS’ approach for defining applicable settings, we caution that emergency departments may require different appropriate use criteria due to their focus on quickly assessing and stabilizing patients. Use of the measure OP-15: Use of Brain Computed Tomography (CT) in the Emergency Department for Atraumatic Headache in the Hospital Outpatient Quality Reporting (OQR) program highlighted the challenges with defining appropriateness in the ED setting, including inconsistency in guidelines and inability to capture information on underlying patient characteristics that can help determine the appropriateness of a procedure. In implementing the AUC program, CMS should consider how AUC might vary by setting .

AUC Development by Provider-led Entities

CMS proposes that AUC developed, modified or endorsed by a qualified provider-led entity will serve as the AUC professionals must consult when ordering applicable imaging services. CMS proposes that a provider-led entity would include national professional medical specialty societies (for example, the American College of Radiology and the American Academy of

Family Physicians) or an organization that is composed primarily of providers and is actively engaged in the practice and delivery of healthcare (for example, hospitals and health systems).

Additionally, CMS proposes that in order to remain or become a qualified provider-led entity, entities must demonstrate the following: systematic literature review, AUC development led by a multidisciplinary team, and public transparency in AUC development. We suggest CMS clarify that the definition of provider-led entity include alliances of providers that deliver healthcare even though the organization itself may not (i.e., organizations that represent providers and health systems or a collaborative of providers and health systems formed to develop AUC).

PRIMARY CARE AND CARE MANAGEMENT SERVICES

CMS has received input from stakeholders that the current E/M office/outpatient visit CPT codes do not reflect all the services and resources involved with furnishing comprehensive, coordinated care management for certain categories of beneficiaries. CMS is interested in ways to improve beneficiary access to care management and seeks information about the clinical status of beneficiaries receiving these services and the resources involved in providing such services.

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 16 of 19

Improved Payment for the Professional Work of Care Management Services

The Premier healthcare alliance applauds CMS for trying to provide proper incentives for physicians and other practitioners to provide care management services. We believe the best way to do this is to create a new HCPCS code as opposed to an add-on code to E/M services, given this work is often performed separate from a face-to-face visit with the patient. For example, when a patient experiences a significant loss of cognitive function, such as a dementia patient, a physician would need to arrange appropriate evaluations, family planning and patient counseling, and likely interact with local or state organizations for proper care, most of which would take place when the patient is not present. CMS should establish additional care management codes for accounting for professional work that takes place separately from E/M visits.

CCM Services

Management needs of patients can vary greatly over time. There are many chronic conditions that require more extensive care management at specific points in the disease’s etiology, for which primary care physicians (PCP) and their staff need substantially more reimbursement than the typical monthly care management fee to cover costs. For example, when a hepatitis C patient begins to show signs of cirrhosis, the PCP and clinical staff may need to spend hours of time scheduling follow-up visits and lab tests, conducting medication reconciliation, and coordinating care with a specialty pharmacy and the patient’s hepatologist. These periods of intensified chronic care management often cannot be anticipated ahead of time. There may be a mechanism for using ICD-10 coding of disease severity to distinguish these spikes in patient management needs. CY 2016 could serve as a data collection period to provide examples of coding for intense periods of complex chronic disease management. The Premier healthcare alliance recommends CMS allow for more frequent billing of the chronic care management codes or create a severity adjustment mechanism to the current code.

In improving payment for transitional care and chronic care management, CMS should do its best to avoid increasing the financial burden to the at-risk beneficiaries it is trying to help.

Requiring cost-sharing for those services creates additional and unnecessary barriers to their utilization. CMS should do all it can to bring down those barriers, considering these patients are potentially the most expensive to the Medicare system if their chronic conditions go unmanaged.

One option is for Medicare to cover care management services similarly to preventive care services, which the beneficiary can receive at no cost. To improve access to transitional and chronic care management services, the Premier healthcare alliance asks CMS to pursue waivers of cost-sharing for care coordination codes, either by rulemaking or, if necessary, by requesting new statutory authority.

While most of the scope of service requirements for billing the CCM services are reasonably applicable to physician practices, communicating the care plan to all community providers electronically is not always possible for hospitals or clinicians. Not all community practitioners have a way to receive encrypted email or electronic messages other than fax, which in many cases is completely electronic. The Premier healthcare alliance strongly encourages CMS to

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 17 of 19 allow the care plan to be shared via fax with community providers when electronic options are not available.

Establishing Separate Payment for Collaborative Care

CMS believes that the care management for Medicare beneficiaries with multiple chronic conditions or common behavioral conditions can require extensive discussion, information sharing and planning between a primary care physician and a specialist. This work often occurs outside of patient encounters. CPT created four codes that describe interprofessional telephone/Internet consultative services (CPT codes 99446-99449), but CMS does not make separate payment for these services as they are considered part of other services furnished to beneficiaries. Allowing a primary care physician and the specialist to receive separate payment for interprofessional consultative services would help alleviate the deficit of non-reimbursable time spent managing care for a patient with complex chronic conditions. The Premier healthcare alliance strongly supports separate payment for interprofessional consultative services, and billing for these services should not be limited to beneficiary encounters.

ADVANCE CARE PLANNING

In the CY 2015 final rule, CMS decided not to provide payment for newly created codes describing advanced care planning (CPT code 99497, face-to-face ACP with patient, family members and/or surrogate including explanation of advance directives by the physician or other qualified health professional for the first 30 minutes and CPT code 99498, ACP, each additional

30 minutes), but now requests comment on providing separate payment for these codes. The codes can be billed with or without an evaluation and management service. Additionally, CMS seeks comment on whether separate payment is appropriate at the time of the annual wellness visit. The Premier healthcare alliance applauds CMS for promoting advance care planning and recognizing that advance care planning discussions require significant time for providers. Advanced care planning should also be a separate payment at other times of service, such as the welcome to Medicare visit and the annual wellness visit.

MEDICARE TELEHEALTH SERVICES

Medicare makes payment for telehealth services furnished by physicians and practitioners. CMS notes that in the past regulations, they omitted certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) from the list of distant site practitioners for telehealth services because they did not believe

CRNAs would furnish any of the services on the list of Medicare telehealth services. CRNAs are licensed in some states to furnish some of the services on the telehealth list, including E/M services, and CMS is proposing to revise the regulations to include a CRNA. The Premier healthcare alliance applauds CMS for making this revision to the regulation.

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 18 of 19

PHYSICIAN SELF-REFERRAL

CMS proposes many changes to the regulations implementing the physician self-referral law under section 1877 of the Social Security Act. Premier is generally very supportive of proposals that reduce the burden of compliance with section 1877 on providers of services and physicians, especially in light of recent congressional legislation designed to improve the quality and efficiency of care delivery under Medicare's fee-for-service program. When first enacted into law, the physician self-referral statute addressed a vastly different healthcare delivery landscape than the one that exists today.

With the addition of payment incentives and penalties for performance of Medicare providers and physicians, as well as new healthcare delivery models for fee-for-service beneficiaries, such as accountable care organizations, and new payment models, such as bundled payments, closer integration is required among providers and physicians, both clinically and financially. Thus, proposals to reduce administrative burdens on providers (through clarifications of existing requirements or elimination of others) as well as proposals to provide additional exceptions to the physician self-referral law or additional waivers will afford providers and practitioners the certainty as well as additional flexibility needed to successfully participate in the reforms and new models, while still protecting against fraud or abuse against the Medicare program.

Exception for Recruitment of Certain Non-physician Practitioners

CMS proposes a new exception for hospitals to provide remuneration to physicians to assist with the employment of non-physician practitioners (NPPs) in the hospitals' geographic service areas.

The exception would protect direct compensation arrangements (between a hospital and an individual physician) and indirect compensation arrangements (between the hospital and a physician “standing in the shoes” of a physician organization to which the hospital provided remuneration).

CMS proposes to limit the types of NPPs for which this exception would apply to nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinic nurse specialists and certified nurse midwives. CMS specifically excludes certified registered nurse anesthetists from its proposal. Additionally, under the proposed exception, NPPs must primarily furnish primary care services which CMS proposes to define as general family practice, general internal medicine, pediatrics, geriatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology. CMS seeks comment on other types of NPPs with respect to which the proposed exception should apply.

Premier strongly supports the proposed exception to encourage the recruitment of NPPs to expand access to primary care services. As NPPs play an increasingly important role in meeting the need for healthcare services in light of physician shortages, which in some areas are

Mr. Andrew M. Slavitt

September 8, 2015

Page 19 of 19 severe, CMS should encourage this and other policies to use NPPs to alleviate barriers and improve access to healthcare services, especially primary care services.

Premier finds the majority of the proposed safeguards to be largely reasonable. However,

Premier adamantly disagrees with the exception's proposed exclusion of certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) from the list of eligible NPPs. If the policy goal is to expand access to primary care services through NPPs where physicians are unable to meet the need, it seems counterintuitive to exclude a category of NPPs who, pursuant to state law, may be licensed in their jurisdictions to provide evaluation and management services as well as other services that would fit the proposed definition of primary care services. In this same proposed rule, CMS itself acknowledges that CRNAs can play an important role in the delivery of these services by proposing to add CRNAs to the list of practitioners under section 1834(m)(4)(E) of the Act who may provide Medicare telehealth services. CMS notes in the preamble to the proposal to add

CRNAs to the list of eligible telehealth practitioners that it “…initially omitted CRNAs from the list of distant site practitioners for telehealth services in the regulation because we did not believe these practitioners would furnish any of the service on the list of Medicare telehealth services.

However, CRNAs in some states are licensed to furnish certain services on the telehealth list, including E/M services. Therefore, we propose to revise the regulation at §410.78(b)(2) to include a CRNA, as described under §410.69, to the list of distant site practitioners who can furnish Medicare telehealth services.” CMS should follow the same policy with respect to the

CRNAs under the proposed recruitment exception to the physician self-referral law and regulations as it proposes to apply under the telehealth expansion policy in this same rule.

Premier strongly encourages CMS to include CRNAs in the list of NPPs for purposes of this proposed new exception. There is no evidence to suggest that CRNAs are more likely than any other NPPs to commit fraud or abuse against the program, and CMS has proposed a range of safeguards which when applied to NPPs, including CRNAs, should alleviate any concerns for risks of fraud or abuse. The addition of CRNAs to the list of NPPs would improve access to primary care services in many states, and beneficiaries, especially in physician shortage areas, should be afforded as broad a range of primary care service practitioners as possible to improve access to basic care needs.

CONCLUSION

In closing, the Premier healthcare alliance appreciates the opportunity to submit these comments on the CY 2016 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule. If you have any questions regarding our comments or need more information, please contact Danielle Lloyd, VP, policy & advocacy and deputy director DC office, at danielle_lloyd@premierinc.com

or 202.879.8002.