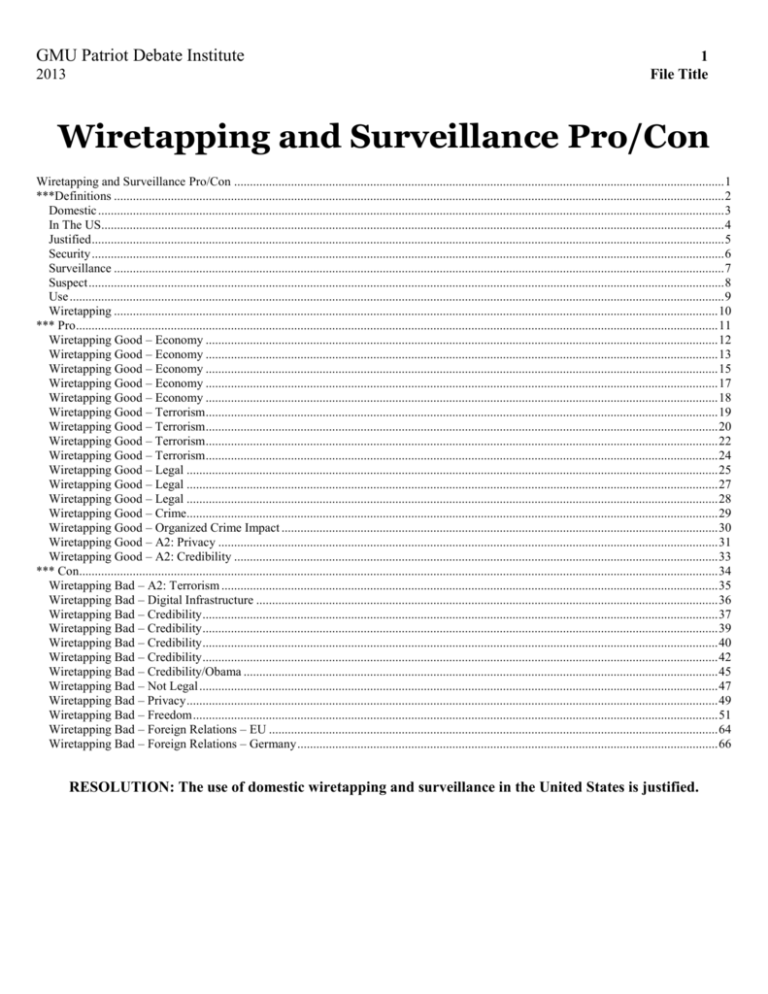

Wiretapping Good – Legal - George Mason Debate Institute / Home

advertisement