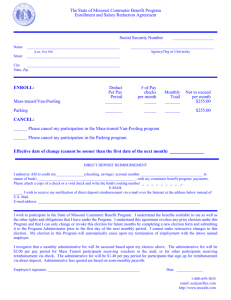

C. Political yard signs. Many people like to express their support for

advertisement