CASI 8

advertisement

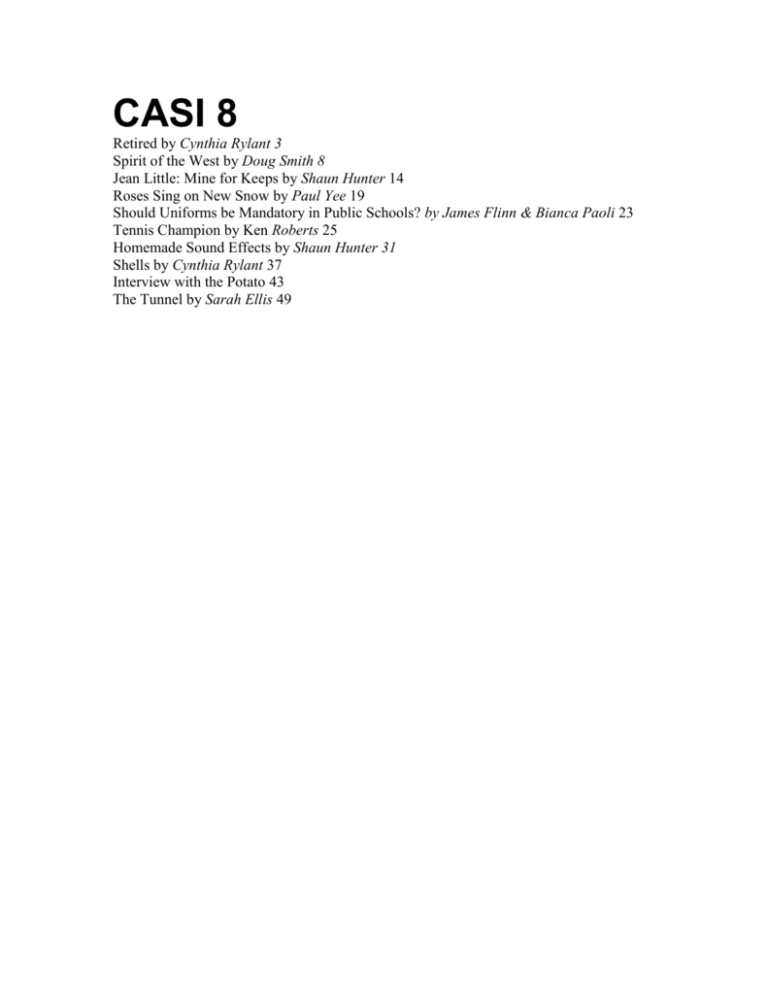

CASI 8 Retired by Cynthia Rylant 3 Spirit of the West by Doug Smith 8 Jean Little: Mine for Keeps by Shaun Hunter 14 Roses Sing on New Snow by Paul Yee 19 Should Uniforms be Mandatory in Public Schools? by James Flinn & Bianca Paoli 23 Tennis Champion by Ken Roberts 25 Homemade Sound Effects by Shaun Hunter 31 Shells by Cynthia Rylant 37 Interview with the Potato 43 The Tunnel by Sarah Ellis 49 Why Miss Cutcheon decided one day to walk Velma a few blocks farther, and to the west, is a puzzle. Retired by Cynthia Rylant Her name was Miss Phala Cutcheon and she used to be a schoolteacher. Miss Cutcheon had gotten old and had retired from teaching fourth grade, so now she simply sat on her porch and considered things. She considered moving to Florida. She considered joining a club for old people and learning to play cards. She considered dying. Finally, she just got a dog. The dog was old. And she, too, was retired. A retired collie. She had belonged to a family who lived around the corner from Miss Cutcheon. The dog had helped raise three children, and she had been loved. But the family was moving to France and could not take their beloved pet. They gave her to Miss Cutcheon. When she lived with the family, the dog's name had been Princess. Miss Cutcheon, however, thought the name much too delicate for a dog as old and bony as Miss Cutcheon herself, and she changed it to Velma. It took Princess several days to figure out what Miss Cutcheon meant when she called out for someone named Velma. In time, though, Velma got used to her new name. She got used to Miss Cutcheon's slow pace--so unlike the romping of three children - and she got used to Miss Cutcheon's dry dog food. She learned not to mind the smell of burning asthmador, which helped Miss Cutcheon breathe better, and not to mind the sound of the old lady's wheezing and snoring in the middle of the night. Velma missed her children, but she was all right. Miss Cutcheon was a very early riser (a habit that could not be broken after fortythree years of meeting children at the schoolhouse door), and she enjoyed big breakfasts. Each day Miss Cutcheon would creak out of her bed like a mummy rising from its tomb, then shuffle into the kitchen, straight for the coffee pot. Velma, who slept on the floor at the end of Miss Cutcheon's bed, would soon creak off the floor herself and head into the kitchen. Velma's family had eaten cold cereal breakfasts all those years, and only when she came to live with Miss Cutcheon did Velma realize what perking coffee, sizzling bacon and hot biscuits smell like. She still got only dry dog food, but the aromas around her nose made the chunks taste ten times better. Miss Cutcheon sat at her dinette table, eating her bacon and eggs and biscuits, sipping her coffee, while Velma lay under the table at her feet. Miss Cutcheon spent most of breakfast time thinking about all the children she had taught. Velma thought about hers. During the day Miss Cutcheon took Velma for walks up and down the block. The two of them became a familiar sight. On warm, sunny days they took many walks, moving at an almost brisk pace up and back. But on damp, cold days they eased themselves along the sidewalk as if they'd both just gotten out of bed, and they usually went only a half-block, morning and afternoon. Miss Cutcheon and Velma spent several months together like this: eating breakfast together, walking the block, sitting on the front porch, going to bed early. Velma's memory of her three children grew fuzzy, and only when she saw a boy or girl passing on the street did her ears prick up as if she should have known something about children. But what it was she had forgotten. Miss Cutcheon's memory, on the other hand, grew better every day, and she seemed not to know anything except the past. She could recite the names of children in her mind-which seats they had sat in, what subjects they were best at, what they'd brought to school for lunch. She could remember their funny ways, and sometimes she would be sitting at her dinette in the morning, quietly eating, when she would burst out with a laugh that filled the room and made Velma jump. Why Miss Cutcheon decided one day to walk Velma a few blocks farther, and to the west, is a puzzle. But one warm morning in September, they did walk that way, and when they reached the third block, a sound like a million tiny buzz saws floated into the air. Velma's ears stood straight up, and Miss Cutcheon stopped and considered. Then they went a block farther, and the sound changed to something like a hundred bells pealing. Velma's tail began to wag ever so slightly. Finally, in the fifth block, they saw the school playground. Children, small and large, ran wildly about, screaming, laughing, falling down, climbing up, jumping, dancing. Velma started barking, again and again and again. She couldn't contain herself. She barked and wagged and forgot all about Miss Cutcheon standing there with her. She saw only the children and it made her happy. Miss Cutcheon stood very stiff a while, staring. She didn't smile. She simply looked at the playground, the red brick school, the chain-link fence that protected it all, keeping intruders outside, keeping children inside. Miss Cutcheon just stared while Velma barked. Then they walked back home. But the next day they returned. They moved farther along the fence, nearer where the children were. Velma barked and wagged until two boys, who had been seesawing, ran over to the fence to try to pet the dog. Miss Cutcheon pulled back on the leash, but too late, for Velma had already leaped up against the wire. She poked her snout through a hole and the boys scratched it, laughing as she licked their fingers. More children came to the fence, and while some rubbed Velma's nose, others questioned Miss Cutcheon: "What's your dog's name?" "Will it bite? .... Do you like cats?" Miss Cutcheon, who had not answered the questions of children in what seemed a very long time, replied as a teacher would. Every day, in good weather, Miss Cutcheon and Velma visited the playground fence. The children learned their names, and Miss Cutcheon soon knew the children who stroked Velma the way she had known her own fourth-graders years ago. In bad weather, Miss Cutcheon and Velma stayed inside, breathing the asthmadora, feeling warm and comfortable, thinking about the children at the playground. But on a nice day, they were out again. In mid-October, Miss Cutcheon put a pumpkin on her front porch, something she hadn't done in years. And on Halloween night, she turned on the porch light, and she and Velma waited at the door. Miss Cutcheon passed out fifty-six chocolate bars before the evening was done. Then, on Christmas Eve of that same year, a large group of young carolers came to sing in front of Miss Cutcheon's house; and they were bearing gifts of dog biscuits and sweet fruit. Spirit of the West by Doug Smith Today, most mustangs in North America are protected, but they still have trouble finding enough room to roam. When you think of horses, what comes to mind? Depending upon where you live, you may picture cowboys and bucking rodeo broncos or show jumpers or maybe a horse you saw or rode at a fair, a farm, or stable. Chances are that whatever idea popped into your head, it probably included at least one person, which is not surprising, considering that humans have been domesticating horses for more than 6000 years. But what about the horses with no owners, like those running free in the wilds of western North America? The First Mustangs Until 8000 years ago, wild horses roamed across much of North America. No one really knows why they died out--perhaps it was climate change, or maybe they were hunted to extinction by early humans---but horses were not seen again in the Americas until the late-15th century. That's when Spanish explorers - including Christopher Columbus arrived looking for gold in the New World. It wasn't long before some of their horses escaped or, in some cases, were turned loose. They became the first mustangs, or mestenos---the Spanish word for stray or feral animals-- to roam free. Fast Facts Found: Parts of western North America Height: 12 to 14 hands (122-142 centimetres or 48-56 inches) at the shoulders Weight: 295 to 455 kilograms (650-1000 pounds) Mainly grass, also other leaves, twigs, and roots Alpine meadows provide summer food for many of the mustangs in the Pryor Mountain Wild Home Range. When Native Americans first caught a glimpse of the Spanish soldiers on horseback, they thought the horses and riders were magical beings--half human and half animal. But when they realized that they were seeing two separate creatures, they wanted horses of their own. Soon they, too, were using horses for hunting and travelling. Eventually, some of their horses also escaped and joined the horses lost by the Spanish on the prairies. Wild 'n' Free. Before long, thousands of mustangs were running free in the West from Mexico to Canada, and by the late 1800s, there were an estimated two million horses in the wild. At the same time, however, humans were also rapidly expanding their range. And as ranches and farms spread, hundreds of thousands of horses were captured and killed to make way for livestock and crops. Others were caught, tamed, and then sent off with soldiers to fight in the Boer War and World War I. This took a tremendous toll on the mustang population and by the late 1960s, a mere 17 000 remained. Wild Horse Annie. Then a Nevada woman named Velma Johnston--who later became known as Wild Horse Annie---came to the horses' rescue. After seeing first-hand how the mustangs were being treated, she begged the government to do something to protect the horses. And when that didn't work, she organized a writing campaign among schoolchildren. After politicians started receiving thousands of letters, they began to take notice. Nine years later, the "Wild Horse Annie" law, which banned using vehicles or polluting water holes to capture horses, was passed. And in 1971, another, tougher law was introduced in the United States stating that "wild and free-roaming horses and burros are living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West" and as such should be protected from capture, harassment, and death. The government also set aside a number of refuges for the horses. One such reserve is the Pryor Mountain Wild Horse Range on the Montana-Wyoming border. The area, which is home to 140 mustangs, is also a popular hangout for photographers eager to get mustang shots. MUSTANGS in Hollywood Maybe one day you'll get a chance to see mustangs running free in the wild, but in the meantime, you can cheer them out on the big screen. The animated movie Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron is about the adventures of a wild and rambunctious mustang stallion as he journeys through the untamed American frontier. The film is told from the viewpoint of Spirit and is narrated by Matt Damon. Set in the Wild West in the 1800s, the story tells of Spirit's first encounters with humans and his discovery of the effect the expanding civilization will have on his freedom. (He also meets a beautiful paint mare named Rain that he immediately falls in love with, and he develops a remarkable friendship with a Lakota brave.) Despite Spirit's repeated attempts to avoid capture, in the end he is caught by the cavalry and trained to be a warhorse. Although the movie is animated and fictitious, Dream Works' producers wanted Spirit to look the part, so they bought a Kiger stallion - a breed that descended from the original Spanish mustang to be a model for the horse. Foals (left) live in the family band, which consists of a stallion and his mares (or harem), until they are two to three years old. Stallion encounters (above) involve a lot of prancing and neck arching. But if neither male backs away, the horses may duel and try to knock each other over by kicking with their front legs. At Last Count Today, there are roughly 42 000 mustangs in western North America. Nevada is home to more than half the wild horses in the U.S., and there is also a large population in Wyoming. The rest are scattered in small pockets in eight other states. There are also a few hundred mustangs in Canada. One herd lives in B.C.'s Chilcotin Range and another in the Siffleur Wilderness Area, near Banff National Park, Alberta. Neither population has any legal protection; however, one B.C. environmental group is campaigning for a National Chilcotin Wild Horse reserve. Looking to the Future Even today, the controversy surrounding the mustangs continues. Because the horses reproduce rapidly and have few natural predators, their populations double every four to seven years. Left unchecked, they quickly outgrow their food supply, which can lead to starvation, as well as competition for resources with cattle and native wildlife. To keep numbers down, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management rounds up horses, using crews of wranglers on horseback and helicopters. Some of the captured horses are released, while others are put up for adoption. (Canada has adopted a similar program.) Unfortunately, in every roundup, there are some horses that are unadoptable-perhaps, because they can't be tamed or they just don't look attractive. So what happens to them? Some find homes on reserves, but there is simply not enough space to fill the demand. One solution that is meeting with some success is having inmates at a Colorado state prison help tame the mustangs before they are adopted. Scientists are also looking into possible birth-control methods for the horses to prevent the populations from growing so fast in the future. When there is not enough grass and water to support a mustang herd, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management conducts roundups and the mustangs are put up for adoption. No one really knows what lies in store for the mustangs, but if they are strong enough to thrive in some of North America's harshest environments, there's a good chance they'll still be running wild and free well into the future. Mighty Mustangs Chow Down! Because horses have very inefficient digestive systems, they need to chew their food until it is soft and mushy. Since they eat up to 14 kilograms of food a day, they can sometimes spend over half of their time just chewing! Full Alert In addition to a keen sense of smell and hearing, mustangs can feel vibrations in the ground through their legs and will flee at the first sign of danger. Wild Colours Some mustangs have a dark stripe that runs down their back from the mane to the tail or faint zebralike markings on their upper legs. The usual coat colour is bay (reddish brown with black mane, tail, and lower legs), but black and sorrel (yellowish brown) are also common. Other colour variations are black, brown, grey, gold, and white. Family Rules While they may seem wild and carefree, mustangs follow strict ranking within a band, or family group. The stallion is the head of the family and next in importance is the lead mare. When the band moves, she leads the group and the other mares and young follow in single file, with the stallion pulling up the rear. Nip & Clip Mustangs often nibble at each other's necks to free tufts of matted hair or dead and itchy skin. Then they work their way down the sides and back of their partner. Key Events 1939 Returns to Canada from Taiwan at age seven 1947 Self-publishes her first book of poems at age fifteen 1955 Graduates at the top of her class at the University of Toronto 1962 Publishes her first novel, Mine for Keeps 1982 Attends the Seeing Eye School in New Jersey 1986 Writes Different Dragons using a talking computer "I write books about children and the thorny problems that beset them ... because I remember how it was." Jean with her mother and dog Zephyr. Jean was a good storyteller. She often got herself out of scrapes at school by telling a story. 1932 – Jean Little Mine for Keeps by Shaun Hunter Early Years Jean Little spent the first seven years of her life in Taiwan. Both her parents were Canadian medical doctors working as missionaries. Jean was born with scars that covered the pupils of her eyes. As she grew, her vision slowly improved. But almost everything Jean saw was blurry. Her parents wanted to make sure that their daughter did not see herself as disabled. Along with her two brothers and sister, Jean had a busy and active childhood. BACKGROUNDER Raising Children with disabilities Jean's parents were determined not to treat their daughter differently because of her poor eyesight. Even though Jean often stumbled and fell, her parents encouraged her to play with the other children in the mission. Jean even climbed trees with her friends. Jean did not know she was different from other children until she was five. When she was older, children called her "cross-eyed," but by then Jean took comfort in reading and her talent for writing. As a young girl, Jean loved listening to stories. She could hardly wait to learn how to read. Her mother ordered special books from Canada with large print. With a great deal of hard work, Jean learned how to read. Jean's parents Jean at age six with her brother Hugh at Repulse Bay, Hong Kong. "If I wanted to read what was written on the board [at school] I would have to stand up so that my face was only inches away from the writing. Then I would have to walk back and forth, following the words not only with my eyes but with my entire body." Jean at age seventeen. decided to move their young family back to Canada where Jean could attend a special class in the same school as her brothers and sister. Developing Skills At school, Jean was an outsider. She had few friends and was often teased by the other children. Jean coped with her loneliness. She became very close to her family. She also found strength in books and her imagination. Jean was a good storyteller. She often got herself out of scrapes at school by telling a story. In fifth grade, she began writing her own stories. Soon, she began writing poetry. Jean's father supported his daughter's writing. He was an amateur writer himself. He helped publish thirty of her poems and sold the small book to friends and family. He told Jean, 'This is only your first book." Jean decided to study literature at university. Her teachers at the University of Toronto did not think she could handle all the reading she would have to do. She convinced them to let her try. She hired readers at first but found this way of learning too slow. Her father helped her with research. However, during her second year, he had a heart attack and died. Jean continued with her studies alone. She did her own reading and relied on her listening skills and her memory. Four years after starting university, she graduated first in her class. After graduation, Jean took courses on teaching children with disabilities. She returned to her hometown, Guelph, Ontario, to help organize a school for children with muscular difficulties. The idea of writing a novel, however, was always in Jean's mind. At university, she had written a short novel and submitted it to a publisher. The manuscript was returned, but the publisher said she had talent as a writer. When she was twenty-eight, Jean took a year off teaching to give novel- writing a second try. She wrote the story of a girl living with cerebral palsy, a disability that affects the muscles. In 1961, Mine for Keeps won the award for the year's best Canadian children's book. BACKGROUNDER Children with Disabilities in Literature When Jean was teaching children with disabilities, she began looking for better stories to read to them. Jean was frustrated with books about people with disabilities. They always seemed to end with a wonderful cure or death. Jean believed that all children, including children with disabilities, have a need to find themselves represented in fiction. With her first novel, Mine for Keeps, Jean provided children with disabilities an opportunity to read about children like themselves. During her years as a teacher, Jean studied education at the University of Utah in the summer. One year, she took a course in creative writing taught by an award-winning children's author. This course inspired Jean to consider a career in writing. The success of Mine for Keeps allowed Jean to quit her teaching job. She decided to become a full-time writer. However, her sight was getting worse. She had several unsuccessful operations to improve it. Finally, her doctors decided to remove her left eye. Accomplishments Despite losing one eye, Jean continued to write. Through the 1960s and 1970s, she wrote eleven books for young readers. Jean has written about children with disabilities such as cerebral palsy and blindness. But many of her books are about able-bodied children coping with death, loneliness, family, and friendship. She travelled throughout North America to give readings. Eventually, she began having problems with her right eye. She could no longer live or travel alone. She could not type. Jean became depressed and angry. Jean did not want to give up writing. She developed a way to write using two tape recorders and a typist. But writing was slow and frustrating. In 1984, she had finished Mama's Going to Buy You a Mockingbird. This book had taken seven years to write. Two things happened to change Jean's life. First, she was accepted by the Seeing Eye School, the oldest guide dog school in North America. At age fifty, she became a student again. After weeks of difficult training, she received her first seeing eye dog, Zephyr. Second, Jean heard about a new development in computer technology. A blind man living close to Jean had developed software that could translate the human voice into written form. With the help of grants and donations, Jean got her own talking computer. She calls her computer SAM (for synthesized audio microcomputer). With Zephyr and SAM, Jean had the independence she needed to continue her writing. BACKGROUNDER Meeting Rosemary Sutcliffe Jean had always admired the work of the British writer Rosemary Sutcliffe. Rosemary had been writing historical fiction for young people for many years. Jean had read Rosemary's novel Warrior Scarlet to her students. She and her students found the story of the young hero disabled in battle believable and compelling. During her own surgeries, Jean had also found strength and inspiration in Rosemary's books. She sent copies of her first two books to Rosemary and received warm praise in return. Jean had no idea that Rosemary had been disabled since childhood by a form of juvenile arthritis. In 1965, during a European trip, Jean arranged to meet Rosemary. The two writers formed a lasting friendship. Quick Notes In her 1995 book, His Banner over Me, Jean tells the story of her mother. Flora Little was one of the first female doctors in Canada. Jean has written two autobiographies, Little by Little: A Writer's Education (1987) and Stars Come Out Within (1990). Jean (second from left) and her seeing eye dog Zephyr, with their class at the Seeing Eye School. "I wanted to be a writer, but I had been told over and over again that you could not make a living as a writer. You had to get a real job and write in your spare time." Jean at age fifty-nine with her seeing eye dog Ritz. In no time she had fashioned a dish of delectable flavours and aromas, which she named Roses Sing on New Snow. Roses Sing on New Snow by Paul Yee. Seven days a week, every week of the year, Maylin cooked in her father's restaurant. It was a spot well known throughout the New World for its fine food. But when compliments and tips were sent to the chef, they never reached Maylin because her father kept the kitchen door closed and told everyone that it was his two sons who did all the cooking. Maylin's father and brothers were fat and lazy from overeating, for they loved food. Maylin loved food too, but for different reasons. To Chinatown came men lonely and cold and bone-tired. Their families and wives waited in China. But a well-cooked meal would always make them smile. So Maylin worked to renew their spirits and used only the best ingredients in her cooking. Then one day it was announced that the governor of South China was coming to town. For a special banquet, each restaurant in Chinatown was invited to bring its best dish. Maylin's father ordered her to spare no expense and to use all her imagination on a new dish. She shopped in the market for fresh fish and knelt in her garden for herbs and greens. In no time she had fashioned a dish of delectable flavours and aromas, which she named Roses Sing on New Snow. Maylin's father sniffed happily and went off to the banquet, dressed in his best clothes and followed by his two sons. Now the governor also loved to eat. His eyes lit up like lanterns at the array of platters that arrived. Every kind of meat, every colour of vegetable, every bouquet of spices was present. His chopsticks dipped eagerly into every dish. When he was done, he pointed to Maylin's bowl and said, "That one wins my warmest praiseI It reminded me of China, and yet it transported me far beyond. Tell me, who cooked it?" Maylin's father waddled forward and repeated the lie he had told so often before. "Your Highness, it was my two sons who prepared it." "Is that so?" The governor stroked his beard thoughtfully. "Then show my cook how the dish is done. I will present it to my emperor in China and reward you well!" Maylin's father and brothers rushed home. They burst into the kitchen and forced Maylin to list all her ingredients. Then they made her demonstrate how she had chopped the fish and carved the vegetables and blended the spices. They piled everything into huge baskets and then hurried back. A stove was set up before the governor and his cook. Maylin's brothers cut the fish and cleaned the vegetables and ground the spices. They stoked a fire and cooked the food. But with one taste, the governor threw down his chopsticks. "You imposters! Do you take me for a fool?" he bellowed. 'That is not Roses Sing on New Snow!" Maylin's father tiptoed up and peeked. "Why ... why, there is one spice not here," he stuttered. 'Name it and I will send for it!" roared the impatient governor. But Maylin's father had no reply, for he knew nothing about spices. Maylin's older brother took a quick taste and said, "Why, there's one vegetable missing!" "Name it, and my men will fetch it!" ordered the governor. But no reply came, for Maylin's older brother knew nothing about food. Maylin's other brother blamed the fishmonger. "He gave us the wrong kind of fish!" he cried. "Then name the right one, and my men will fetch it!" said the governor. Again there was no answer. Maylin's father and brothers quaked with fear and fell to their knees. When the governor pounded his fist on the chair, the truth quickly spilled out. The guests were astounded to hear that a woman had cooked this dish. Maylin's father hung his head in shame as the governor sent for the real cook. Maylin strode in and faced the governor and his men. "Your Excellency, you cannot take this dish to China!" she announced. "What?" cried the governor. 'You dare refuse the emperor a chance to taste this wonderful creation?" "This is a dish of the New World," Maylin said. 'You cannot recreate it in the Old." But the governor ignored her words and scowled. "I can make your father's life miserable here," he threatened her. So she said, "Let you and I cook side by side, so you can see for yourself." The guests gasped at her daring request. However, the governor nodded, rolled up his sleeves, and donned an apron. Together, Maylin and the governor cut and chopped. Side by side they heated two woks, and then stirred in identical ingredients. When the two dishes were finally finished, the governor took a taste from both. His face paled, for they were different. "What is your secret?" he demanded. 'We selected the same ingredients and cooked side by side!" "If you and I sat down with paper and brush and black ink, could we bring forth identical paintings?" asked Maylin. From that day on Maylin was renowned in Chinatown as a great cook and a wise person. Her fame even reached as far as China. But the emperor, despite the governor's best efforts, was never able to taste that most delicious New World dish, nor to hear Roses Sing on New Snow. In no way are we all the same, so why should we try to be? Should Uniforms be Mandatory in Public Schools? by James Flinn & Bianca Paoli Ever since I was born, I always wanted to be like everyone else, didn't you? I wanted to own the exact same clothes as the Jones'. In fact, I wanted to listen to the same music, drive the same car, and even buy the same brand of toilet paper. Wouldn't the world be a better place if everyone were exactly the same? The truth of the matter is that the world would be bland, dull, and full of conformists. We would lose every aspect of diversity, individuality, and creativity. In a sense, we would be losing ourselves, so why then would somebody want this to happen? The topic of school uniforms has stirred up a lot of controversy in our public school systems. The majority of public schools would like the students to wear a uniform and the majority of the students would like to be able to wear what they want, but which one is right? I would have to say that the idea of forcing every student to wear the exact same clothes as all the other students is absolutely ridiculous. We were all born different. No two people are alike, so why should someone be permitted to try and make each student as similar as possible? The schools think that they have good reasons behind the idea of having all students wear the same uniforms. They think that clothes can be distracting to someone's studies, that the clothing just takes away from the importance of why the student is in school. Clothes express individuality, diversity, and can often tell a lot about a person. Students wear certain clothes for different reasons. They might want to look nice one day and so they decide to dress up. Another day they might want to just wear sweat pants because they want to be comfortable. They also might not have a choice in what they wear because they cannot afford to buy certain clothes or even a uniform for that matter. Students do not wear clothes with the intent of distracting another student, and plus how many times have you heard a student complain, "Teacher I am unable to take my test because John's shirt is incredibly ugly?" The fact is that clothes really do not distract the students, they just bother the teachers. In all seriousness, the students are not the ones complaining and they are the ones who have to learn. The school's biggest argument is that brand name clothing is the cause of much violence in our inner-city schools. Since when did you hear of somebody getting beat up with a pair of Calvin Klein jeans? Wasn't it the gun or the knife that caused the violence? Wouldn't the feeling of power of possessing a weapon be the reason behind taking something from somebody? The schools also think that some T-shirts are too explicit for young children. Students in high school are usually between the ages of 15 and 18, sometimes 19 or 20. These students aren't "children" that still play with He-man and Barbie dolls. Teachers often expect their students to act like adults, but continue to treat them like children. I even knew a guy who was suspended from school for wearing a T-shirt that said, "Bare Naked Ladies." The school board believed that the T-shirt was offensive to women. I do believe that some articles of clothing can be found extremely profane and rather offensive, but that doesn't mean that because of those minimal numbers of offensive T-shirts that students should be forced to wear uniforms. I believe that students have the right to choose what clothes they want to wear. Why should teachers be their fashion critics? The schools are implying that students should all be the same, which they are not. We are all different. We have different hair, different colour eyes, different colour skin, different heights and different weights. In no way are we all the same, so why should we try to be? A school is the place to learn. I believe that art, music, and clothing encourage creativity, individuality, and diversity. I believe that students should know about what makes them different from everyone else. The bottom line is that students should be allowed to choose the clothing that they want to wear. Mark never would have applied to play in the provincial junior championships if someone anyone--in Lac Vert, Quebec, had picked up that second racquet and hit some tennis balls back to him. Tennis Champion by Ken Roberts After the mine closed in Lac Vert, Quebec, the federal government built a tennis court. The federal government built the tennis court in Lac Vert, Quebec, as part of a national fitness campaign. Lac Vert qualified for one single concrete tennis court, complete with net and a chain-link fence. No lights. Lac Vert would have needed a population of four hundred to qualify for lights. After the mine closed, the population of Lac Vert dropped to 173. If the government had used this figure, Lac Vert would only have qualified for a horseshoe pit. People might have used a horseshoe pit more than the tennis court. There were two tennis racquets in all of Lac Vert, Quebec, old racquets Marc Bouchard found in the garage. They had been left behind by a miner years ago. Marc, who was nine years old, found those tennis racquets and borrowed some money from his mother to buy three new tennis balls from Gabe Macaluso's groceteria. Monsieur Macaluso had purchased fifteen bright yellow tennis balls after the federal government built the tennis courts. He was hoping that people would play, which they didn't, so Marc was able to buy three balls on sale. 'Would you like to play tennis?" Marc asked friends at school, who sneered because they only wanted to play hockey and to someday star in the NHL. "Would you like to play tennis?" Marc asked his mom and dad and his older sister, all of whom had lists of several dozen things they'd rather do. 'Would you like to play tennis?" Marc even asked old Mrs. Winters, who travelled through town in a motorized wheelchair, and the mayor, Monsieur Leduc, whom nobody had ever seen without a suit and tie. Nobody wanted to play tennis with Marc. So, Marc played by himself. He served to nobody for two hours a day. He hit his three tennis balls and then walked around the net, picked up all three balls, put them into a wicker basket, placed the basket by his feet and then served his three tennis balls back to the other side. For four years Marc practised all by himself almost every day, even during winter months when the court was clear of snow. Each spring Gabe Macaluso ordered more yellow tennis balls and sold them to Marc. Marc liked serving, and he learned that if he threw the ball higher, giving himself time to put the weight of his body into the swing, then he could hit the ball harder. He learned that if he hit the bail with the racquet held at just the right angle, the ball would hit the concrete and skid to one side instead of travelling straight. Marc never would have applied to play in the provincial junior championships if someone -anyone - in Lac Vert, Quebec, had picked up that second racquet and hit some tennis balls back to him. He wanted the chance to play tennis, to have somebody stand on the other side of the net. The championships were being held in Hull the same day Marc's parents wanted to visit Tante Helene so he filled out an application and wrote that he was the junior tennis champion of Lac Vert, Quebec. Monsieur Macaluso co-signed the form, after putting up a notice in his store window stating that the town's championships would be held that afternoon at 4:00 p.m., and that anybody wanting to play should show up at the court. When nobody except Marc showed up, Gabe Macaluso declared Marc champion by default. He was accepted as a tournament entry since he was the only registered tennis champion for about 100,000 square miles of northern Quebec bush country. Marc's parents didn't mind if he played in the championship. They even bought him an outfit so he'd look like a tennis player. Marc's dad drove him from Tante Helene's house to the country club where the championships were to be held. "Can you hit the ball at all?" asked his father as he opened the door for Marc. Marc's dad didn't plan to stay. "I don't know," answered Marc. "Then why are you playing?" asked his father. "Because I want to serve to somebody. I want somebody to try to return what I hit them. I want to find out if I can hit the ball." "Well, have fun. Call me when you're ready to come home. I guess it might be early." "I guess," said Marc, closing the car door behind him. Marc watched his father drive away and then walked past fourteen perfect, freshly painted tennis courts. On each court stood three or four boys his age, hitting yellow tennis balls back and forth, warming up. Marc stared for a few minutes, his fingers gripping the fence, and then he walked over to the athlete's sign-in desk and told them his name. "First four rounds are single set knockouts," said the woman who handed Marc his schedule. "If you lose, you get to play in the consolation rounds until you lose again." Marc nodded. He knew how to score a set. He'd read the rules that morning. There was no rule book in Lac Vert but his tante lived down the street from a library and Marc had borrowed a book. To prove he knew the rules, Marc said, "In a set the first player to win six games gets the victory so long as the player wins by at least two games, or if the score in games becomes tied at six each, then the first player to win a seven-point tie breaker by two points wins the set." "Right," said the woman, glancing at Marc's old racquet and his high- top basketball shoes. She directed Marc to the court where he was supposed to play. The first person who was going to stand on the other side of a tennis net and hit a ball at Marc was Nicolas Fournier, the junior tennis champion of Gaspe. Nicolas Fournier asked if Marc wanted to warm up and Marc shook his head no. He didn't figure it would do him any good. Marc won the toss and elected to serve first. He stood behind the serving line, told the umpire that he didn't need any practice serves, waited for Nicolas to get into position, tossed a yellow tennis ball into the air and then smacked it. Nicolas's head swivelled around to watch the ball fly past but his legs never moved. "Ace," shouted the umpire. "Server's point." Marc made four straight aces and won the first game. Then he stood, as he had seen Nicolas stand, behind the serving area and waited for Nicolas Fournier to become the first person to hit a tennis bail across the net so that he could try to hit it. Nicolas hit four straight serves and Marc made four swings but missed the ball each time. "One game each," said the umpire. Marc and Nicolas traded games until they'd each won six. Neither had returned one single serve. 'Tiebreaker," shouted the umpire. Marc won the tiebreaker after Nicolas double faulted two straight serves. Marc won his second-round match and his third-round match and then his fourthround match, putting him into the finals. In all of his matches Marc had connected with seven balls hit to him, only one of which went back over the net and won him a point. His opponent was too surprised to swing. A huge crowd sat in the stands for the final three-set championship match. Players and parents gathered to watch Marc serve, the best serve anyone had ever seen a junior tennis player smack, and they came to see if the great Jean Houle, junior tennis champion of Quebec City, could figure out how to return that serve. Marc won the first set on a tiebreaker. He even managed to hit a few balls back, mostly by sticking out his racquet so a hard-hit ball might ricochet across the net. Marc won the second set and the match on a tiebreaker, after Jean double faulted on the twenty-third tiebreaker point. Marc's father, who had come to pick him up, watched his son win the match and receive, to shocked and puzzled applause, the largest trophy anyone in Lac Vert, Quebec, had ever won, even the midget hockey team when it won the provincial championships twentyfour years ago. "Was it fun?" Marc's father asked as he carefully wrapped the tall trophy in a spare blanket and gently nestled it next to the spare tire in the trunk. "Sure," said Marc. "I liked it." "Are you going to play any more of these tournaments?" "Nope. One's enough." Six months later a federal government employee happened to notice that the junior tennis champion of the entire province of Quebec had come from the town of Lac Vert, a place where the government had built a tennis court. "Oh good," thought the federal government employee, "our fitness program was a success. Why, I'll bet they need another tennis court." He was right. Lac Vert, Quebec, did need another tennis court. Marc Bouchard wanted to build rockets and needed a place to launch them. A well-stocked sound-effects kit often looks like a box full of junk left over from a rummage sale... Homemade Sound Effects by Shaun Hunter Try This at Home Take some stiff cellophane (such as a chocolate-bar wrapper), go into the kitchen, and begin to crumple it. Holler in the direction of the living-room that you're frying bacon for everyone, and continue to crumple the wrapper. If your family is hungry, chances are someone will come rushing in to see what's going on. (If everybody's just finished a big meal, the same person might rush in to see if you've gone crazy.) You'll have done what thousands of men and women do every day in radio, TV, and film: you'll have fooled someone with a "sound effect". A Long History People have been using sound effects for a very long time. Tribal hunters mimicked the sound of their prey to confuse the animal or to convince it that no danger lurked nearby. The ancient Greeks employed a loud chorus of voices in their plays to imitate the sound of thunder, a sign that the gods were angry. It wasn't until sound films ("talkies") and radio came along, however, that more realistic sound effects became important. Since the motion pictures and radio dialogue had become very true-to-life, audiences expected the accompanying sounds to be authentic, too. Cellophane Sounds Producers and audio technicians found before long that, if a script called for the sound of frying eggs and bacon, it was much easier (and cheaper) to crumple some cellophane near a microphone than it was to smell up the studio with real bacon crackling in a pan. After all, if you see a picture of eggs frying in a pan and hear crackling sounds, you usually don't stop to consider whether or not it's the eggs making the noise, right? Sound-effects teams found that cellophane could also be used to simulate the sound of a campfire. Add a little mooing and some harmonica music, and you've created a "soundscape" of a lonely cowboy's campfire. For more than fifty years, now, that simple little piece of cellophane has been the mainstay of the sound-effects bag of tricks. Bear Sounds A well-stocked sound-effects kit often looks like a box full of junk left over from a rummage sale - and sometimes that's where sound-effects "props" (short for "properties") come from! Have you ever heard a snarling bear? All you need to re-create this frightening sound is a glass chimney from an old-fashioned kerosene lamp, although nowadays you may have to prowl around garage sales to find one. Take the thick end of the glass and place it over your mouth. Now snarl and grunt into it in your best bear- like fashion. Because the shape of the glass duplicates the shape of a bear's snout, your own puny grunts will be magnified into convincing grizzly growls. Sound Effects Weather If you take the cork ball out of a plastic referee's whistle, the whistle becomes a great device to imitate the sound of wind blowing through a crack in a window. If you'd like to add a little "atmosphere" to the whistling wind, include some thunder and rain. The thunder is easy. You need a piece of bristol board about one metre square. Hold it by one end and shake it up and down. Voila! Thunder! To simulate the sound of rain you'll need: an old window screen, a 50 cm X 50 cm piece of glass or aluminum foil (such as a disposable foil roasting- pan), and a couple of handfuls of uncooked rice. Place the glass (or foil) on a table and hold the screen horizontally a few centimetres above it. Pour the rice onto the screen and gently shake it back and forth. The shaking of the rice and the grains that fall onto the glass below make sounds like raindrops. If you'd like to create the sound of someone walking in the snow on a very cold day, all you need is a box of corn starch. Just take the box in your hands and squeeze. For every step your brave pedestrian takes, give the box another squeeze. Maybe the person slips and breaks a leg. The grisly, bone-crunching sound can be matched by taking a fresh piece of celery or carrot and snapping it in half. This sound effect can also be used to simulate the "crack" of a tree branch being broken. Coconut Shell Hoofbeats Making the sound effect of a horse's hoofbeats can sometimes be tiring, especially if the animal is going on a long journey. To imitate the hoofbeats, you need two halves of a coconut shell. This technique works best if you take out all the white meaty pulp inside. Use the brown husk for the sound effect and the white flesh for a snack. Take half a shell in each hand and hold them hollow-side down. To make the horse walk, tap out a beat with the shells on a small piece of plywood. The rhythm of the beat is very important. Don't tap "left-right, left- fight", because that's the way a two-legged animal would walk. To imitate a horse's gait, tap 'left-right-left, left-right-left." (Some people prefer "right-left-right, right-left-right.") If the horse begins to trot, tap faster. If it begins to run very fast, then you'll have to tap still faster yet. If there's a stone bridge to cross, tap the shells on the classroom chalkboard when the horse is on the bridge, and resume tapping on the wood when it's across. For a horse galloping on grass, tap the shells in a shoe box half full of uncooked rice. Dedicated sound-effects creators also blow air out between their teeth and flap their lips, in order to simulate the horse's satisfied snort when it has just completed a firing run. Not an Easy Job Creating sound effects is not always an easy job. Do you remember the sound of the laser guns in Star Wars? Well, a real laser, which produces an intense beam of light, is absolutely silent. But if the weapons used in the movie hadn't made any noise, the battle scenes wouldn't have been very exciting. So the sound-effects squad hunted for a noise they thought would be appropriate for a futuristic, noisy laser. What they came up with was certainly unusual. That nasal "beeyou" ping of the Star Wars lasers is actually the noise made by plucking a guy wire from a TV antenna. Creating that kind of sound effect takes a trained professional, however; plucking the wrong wire or plucking it the wrong way can bring the whole antenna crashing to the ground. Sounds Like the Real Thing The Russian composer Peter Tchaikovsky wanted to re-create the sound of a war in music. So, for his "18 12 Overture," a piece about the Russian army's defeat of Napoleon, Tchaikovsky used giant drums to imitate the sound of cannons firing. Recently, some orchestras have tried to make the required cannon sounds even more realistic when they perform this music. Some have tried real cannons, others have used fireworks, and many have used tape recordings of cannons firing. But one of the weirdest cannon sound effects is created by dropping a railway tie onto the stage when the guns are supposed to fire. Audience members at concerts where this seemingly dangerous stunt has been done all agree that the crash sounds like the real thing. And that's the greatest compliment a sound- effects creator can receive. Recipe for a Western Ingredients 1 coconut country and western music played on a harmonica; for example, "Red River Valley" several small carrots matches cellophane Instructions 1. Cut coconut in half. Scoop out flesh. Save shells. 2. Turn on harmonica music. 3. Begin to tap coconut shells on desk, remembering to beat properly for horse trotting. 4. After one minute, make "horse snort" sound in mouth. 5. Make rustling sounds of clothing, and begin to tap coconut shells erratically. 6. Stamp feet. 7. Stop tapping shells. 8. Snap in half several small carrots, one after another. 9. Light match. Pause. Blow out match softly. 10. Begin to crumple cellophane; continue crumpling. 11. Yawn, pause, then sigh aloud. 12. Begin to snore. 13. Continue crumpling for one minute, then gently crumple more and more quietly, then stop. 14. Stop snoring. 15. In one minute, stop harmonica music. Yield: One cowpoke going to sleep beside the campfire at the end of a hard day on the range. Homemade Sound Effects on the Internet It's Never a Quiet Week, Anywhere, When Tom Keith Is Around October, 1998 You can hear examples of the different sound effects by either clicking on the title in the descriptions below or clicking on its corresponding letter in the image. Sound Sequence: Click to play all the effects A-K, one after another. (Real Audio 28.8; See How to Listen) Door A, to be opened, closed, and slammed, with multiple locks, each with a different sound. Keith checks the door before each show to make sure it's ready to open and dose on cue. Wingtips (B) picked up at Salvation Army. Used to make footsteps by pressing the heels of the shoes together and rolling toward the toes. Taped box of cornstarch (C): When squeezed, sounds like someone walking through squeaky fresh snow. Styrofoam picnic plates (D): When broken in half, they sound like breaking wood. Telephone (E): Dialing, ringing, etc. Roller skate (F): Makes the sound of an elevator door opening when rolled across the rugged keys of an old typewriter. Need soldiers to march? These wooden legs (G) sound like a whole battalion marching in step. Doorbells (H): buzz or chime. Coconut shells (I) in box of small gravel: A coconut shell in each hand, when crunched one after the other against the gravel, sounds like horses' hooves. Glass-breaking box (J): Toss a wine glass at the angle iron on the bottom and hope you hit it. Crash box (K): Adds drama to a fall. Matched with car horns and breaking glass, it makes a great car accident. SINCE 1976, SOUND EFFECTS WIZARD TOM KEITH and his collection of homemade props have been earning huge applause from A Prairie Home Companion audiences for seemingly impossible sound-effects feats such as a pig jumping off a diving board into a vat full of jello. Esther usually did not intrude in Michael's room, and seeing her there disturbed him. Shells by Cynthia Rylant 'You hate living here." Michael looked at the woman speaking to him. "No, Aunt Esther. I don't." He said it dully, sliding his milk glass back and forth on the table. "I don't hate it here." Esther removed the last pan from the dishwasher and hung it above the oven. "You hate it here," she said, "and you hate me." "I don't!" Michael yelled. "It's not you!" The woman turned to face him in the kitchen. "Don't yell at me!" she yelled. "I'll not have it in my home. I can't make you happy, Michael. You just refuse to be happy here. And you punish me every day for it." "Punish you?" Michael gawked at her. "I don't punish you! I don't care about you! I don't care what you eat or how you dress or where you go or what you think. Can't you just leave me alone?" He slammed down the glass, scraped his chair back from the table and ran out the door. "Michael!" yelled Esther. They had been living together, the two of them, for six months. Michael's parents had died and only Esther could take him in---or, only she had offered to. Michael's other relatives could not imagine dealing with a fourteen-year-old boy. They wanted peaceful lives. Esther lived in a condominium in a wealthy section of Detroit. Most of the area's residents were older (like her) and afraid of the world they lived in (like her). They stayed indoors much of the time. They trusted few people. Esther liked living alone. She had never married or had children. She had never lived anywhere but Detroit. She liked her condominium. But she was fiercely loyal to her family, and when her only sister had died, Esther insisted she be allowed to care for Michael. And Michael, afraid of going anywhere else, had accepted. Oh, he was lonely. Even six months after their deaths, he still expected to see his parents - sitting on the couch as he walked into Esther's living room, waiting for the bathroom as he came out of the shower, coming in the door late at night. He still smelled his father's Old Spice somewhere, his mother's talc. Sometimes he was so sure one of them was somewhere around him that he thought maybe he was going crazy. His heart hurt him. He wondered if he would ever get better. And though he denied it, he did hate Esther. She was so different from his mother and father. Prejudiced--she admired only those who were white and Presbyterian. Selfish-she wouldn't allow him to use her phone. Complaining--she always had a headache or a backache or a stomachache. He didn't want to, but he hated her. And he didn't know what to do except lie about it. Michael hadn't made any friends at his new school, and his teachers barely noticed him. He came home alone every day and usually found Esther on the phone. She kept in close touch with several other women in nearby condominiums. Esther told her friends she didn't understand Michael. She said she knew he must grieve for his parents, but why punish her? She said she thought she might send him away if he couldn't be nicer. She said she didn't deserve this. But when Michael came in the door, she always quickly changed the subject. One day after school Michael came home with a hermit crab. He had gone into a pet store, looking for some small living thing, and hermit crabs were selling for just a few dollars. He'd bought one, and a bowl. Esther, for a change, was not on the phone when he arrived home. She was having tea and a crescent roll and seemed cheerful. Michael wanted badly to show someone what he had bought. So he showed her. Esther surprised him. She picked up the shell and poked the long, shiny nail of her little finger at the crab's claws. "Where is he?" she asked. Michael showed her the crab's eyes peering through the small opening of the shell. 'Well, for heaven's sake, come out of there!" she said to the crab, and she turned the shell upside down and shook it. "Aunt Esther!" Michael grabbed for the shell. "All right, all right." She turned it right side up. "Well," she said, "what does he do?" Michael grinned and shrugged his shoulders. "I don't know," he answered. "Just grows, I guess." His aunt looked at him. "An attraction to a crab is something I cannot identify with. However, it's fine with me if you keep him, as long as I can be assured he won't grow out of that bowl." She gave him a hard stare. "He won't," Michael answered. "I promise." The hermit crab moved into the condominium. Michael named him Sluggo and kept the bowl beside his bed. Michael had to watch the bowl for very long periods of time to catch Sluggo with his head poking out of his shell, moving around. Bedtime seemed to be Sluggo's liveliest part of the day, and Michael found it easy to lie and watch the busy crab as sleep slowly came on. One day Michael arrived home to find Esther sitting on the edge of his bed, looking at the bowl. Esther usually did not intrude in Michael's room, and seeing her there disturbed him. But he stood at the doorway and said nothing. Esther seemed perfectly comfortable, although she looked over at him with a frown on her face. "I think he needs a companion," she said. 'What?" Michael's eyebrows went up as his jaw dropped down. Esther sniffed. "I think Sluggo needs a girl friend." She stood up. "Where is that pet store?" Michael took her. In the store was a huge tank full of hermit crabs. "Oh my!" Esther grabbed the rim of the tank and craned her neck over the side. "Look at them!" Michael was looking more at his Aunt Esther than at the crabs. He couldn't believe it. "Oh, look at those shells. You say they grow out of them? We must stock up with several sizes. See the pink in that one? Michael, look! He's got his little head out!" Esther was so dramatic leaning into the tank, her bangle bracelets clanking, earrings swinging, red pumps clicking on the linoleum--that she attracted the attention of everyone in the store. Michael pretended not to know her well. He and Esther returned to the condominium with a thirty-gallon tank and twenty hermit crabs. Michael figured he'd have a heart attack before he got the heavy tank into their living room. He figured he'd die and Aunt Esther would inherit twenty-one crabs and funeral expenses. But he made it. Esther carried the box of crabs. 'Won't Sluggo be surprised?" she asked happily. "Oh, I do hope we'll be able to tell him apart from the rest. He's their founding father!" Michael, in a stupor over his Aunt Esther and the phenomenon of twenty-one hermit crabs, wiped out the tank, arranged it with gravel and sticks (as well as the plastic scuba diver Aunt Esther insisted on buying) and assisted her in loading it up, one by one, with the new residents. The crabs were as overwhelmed as Michael. Not one showed its face. Before moving Sluggo from his bowl, Aunt Esther marked his shell with some red fingernail polish so she could distinguish him from the rest. Then she flopped down on the couch beside Michael. "Oh, what would your mother think Michael, if she could see this mess we've gotten ourselves into!" She looked at Michael with a broad smile, but it quickly disappeared. The boy's eyes were full of pain. "Oh, my," she whispered. "I'm sorry." Michael turned his head away. Aunt Esther, who had not embraced anyone in years, gently put her arm about his shoulders. "I am so sorry, Michael. Oh, you must hate me." Michael sensed a familiar smell then. His mother's talc. He looked at his aunt. "No, Aunt Esther." He shook his head solemnly. "I don't hate you." Esther's mouth trembled and her bangles clanked as she patted his arm. She took a deep, strong breath. "Well, let's look in on our friend Sluggo," she said. They leaned their heads over the tank and found him. The crab, finished with the old home that no longer fit, was coming out of his shell. Then they dug me up, and trampled on me to squeeze out the water until I was shattered into little bits. Interview with the Potato Published Radio Scripts Note to broadcaster: This script is about understanding and respecting local wisdom and the local practices that are based on that wisdom. Some indigenous crops become central to the culture and survival of a community of people. The way that a community of people cultivates, stores and propagates that crop is an important part of conserving plant biodiversity. This script is about the relationship between the potato and some of its cultivators. MUSIC FADES OUT. Host: (speaking enthusiastically) Greetings to all the listeners tuning in to the show. Today we're going to talk about the history of the potato. And who better to speak than the potato himself? The potato is going to talk to us about the importance of local knowledge and practices. These practices are often passed down to us through many generations. For example, some people cultivate and process potatoes today in much the same way as their ancestors did so many years ago. Now over to our guest. Dear friend, please introduce yourself and tell us where you are from. Potato: (speaking in a young and energetic way) Greetings to all. Yes, I am the potato! I was first grown high in the Andes Mountains in South America about 9000 years ago. But now I live almost everywhere on earth. In fact, I am grown in 148 countries! Host: Yes, you are very popular--I'm sure most of our listeners know you. Can you tell us about your birth and childhood? Potato: I was born in South America. A group of people called the Aymara people were the first to grow me. They lived on the shores of a large lake, called Lake Titicaca, in South America. The Aymara people found wild potatoes growing all around, and began to plant them in their fields. In fact, you can still find wild potatoes around Lake Titicaca--one is called the 'fox potato'. You might say that the fox potato is my great-greatgreat grandparent. But we potatoes looked very different in those days! We were small then, only about the size of a plum. Host: So the Aymara people found potatoes growing wild and began to cultivate them. Was it difficult to grow potatoes so high in the mountains? Potato: It was very cold and dry up on the high plateau where I was born. But the Aymara farmers were very creative. They dug canals and used the soil that they removed from the canals to make raised fields. Then they planted me in the raised fields. The water in the canals kept the soil slightly wet even when the weather was very dry. The canal water also helped to stop the soil from freezing. Host: That was creative! How did the Aymara people prepare and process you? Potato: Well, a lot of the time they dried me, and stored me to eat later. First, they left me in the ground until I froze. Then they dug me up, and trampled on me to squeeze out the water until I was shattered into little bits. Next they dried me all the little bits of me in the sun. Then they stored me in cold underground storage areas they could keep me there for 10 years if they wanted! When they were ready to eat me, they took me out of the cold storage areas, ground me into flour, and made bread from me. And I should tell you that today, in present times, the Aymara people still cultivate, process and store me in much the same way. We have a very special relationship! Host: Okay, so now we know a bit about your relationship with the Aymara people. They were the first to grow you and they found all sorts of interesting ways to store and use you. And today, so many years later, you are still with them. Are there any other people or cultures that you had a special relationship with? Potato: Oh yes. I have enjoyed good relationships with many different communities and cultures. I was VERY popular with the Inca people. They lived in South America hundreds of years after the Aymara people. I don't mean to sound too proud, but I was at the very centre of the Inca culture. Host: (sounding surprised) At the centre of their culture? Were you really THAT important? Potato: Oh yes. I mean, the Incas had potato gods! They made pottery shaped like potatoes. They rubbed me on the skin of sick patients, and used me to help women in childbirth. I was everywhere! Their language has more than one thousand words to describe potatoes and potato varieties. Host: Wow that's a real potato culture! There's one more thing I want to ask you--but please don't be offended. Potato: Please ... go ahead and ask. I'm quite tough and hardy. Host: (sounding incredulous) I've seen white and yellow potatoes. But you are a blue potato! Potato: Well, yes. I come in every colour of the rainbow! White, yellow, red, blue, black, orange, purple, pink ... and in every shape and size! I can be small, large, bumpy, round, smooth, thin or thick. And we potatoes have many different tastes--all good of course! Host: You must be proud to be from a family with so many attractive and delicious varieties. Potato: Yes I am, although I am troubled by some things these days. But maybe we shouldn't go into that now ... (sounding sad) Host: Well yes, please go on ... we still have time. Especially if something is bothering you. Potato: Well, even though there are thousands of kinds of potatoes all over the world, many of the old varieties--the ones that have been around for so many generations are being lost. Host: ( sounding puzzled) Why is that a problem for you? Potato: Let me give you an example to show you why this is a problem. In the Andes mountains where I was born, farmers grow over 200 species of potatoes, and 5000 varieties. To the people of these mountains, different types of potatoes are as different as the meat from a pig and a chicken. They eat one kind of potato for breakfast, another for lunch, and a third for dinner! Of course when potatoes are this important it is very good for our survival. But in some places in the world, only a few varieties are being grown. This can cause BIG problems. Did you ever hear about the Irish potato famine? Over 100 years ago, people in the country of Ireland ate a lot of potatoes that was their main food. But they didn't grow many different varieties of potatoes. A devastating disease called late blight arrived in the country and destroyed most of the potatoes. Perhaps one million people starved to death. This disaster might not have happened if more varieties had been grown. Host: Okay. Now I understand why growing many varieties is important. If I were a farmer, how would you advise me to plant and grow different potato varieties? Potato: Well, to begin, why not grow several varieties in the same field? Consider the colour and temperature of the soil, the steepness of the slope, and how much sun it gets. Then plant the kind of potato that will do best in those conditions. By doing this you make sure that your potatoes have a wide variety of characteristics and personalities, so that they can meet any possible pest or disease challenge. Host: Well, my friend YOU have quite a personality. It's been a pleasure talking with you and I've learned a lot about you and all your relatives. Thank you for coming here today. Do you have any parting words? Potato: All I want to say to the listeners is: Plant a lot of potatoes! Plant many different varieties of potatoes! And eat a lot of potatoes--we're good for you! MUSIC FADES IN (If possible use or compose a song about potatoes.) Fast Facts About the International Potato Center The International Potato Center (ClP) in Lima, Peru, has a collection of • more than 5000 distinct types of wild and cultivated potato • 6500 types of sweet potato • more than 1300 of other Andean roots and tubers The potato collection • contains more than 160 non- cultivated wild species • provides the world's plant breeders with a potential source of traits ranging from cold tolerance to disease resistance People at the Center • work with farmers and plant breeders to ensure the survival and improvement of the many different varieties • conduct research on - sweet potatoes, other root and tuber crops - the improved management of natural resources in the Andes and other mountain areas One of their projects, Papa Andina, works with small-scale farmers to promote potato diversity and link indigenous potato production with market demand. The Center publishes and distributes many publications about their work. To contact them: Website: www.cipotato.org Mail: PO Box 1558, Lima 12, Peru, Telephone: +51 1 349 6017 Fax: +51 1 317 5326 e-mail: Webmaster-ClP@cgiar.org I take a deep breath and I'm there again. That smell. Wet and green and dangerous. The Tunnel by Sarah Ellis When I was a kid and imagined myself older, with a summer job, I thought about being outdoors. Tree planting, maybe. Camping out, getting away from the parents, coming home after two months with biceps of iron and bags of money. I used to imagine myself rappelling down some mountain with a geological hammer rocked into my belt. At the very worst I saw myself sitting on one of those tall lifeguard chairs with zinc ointment on my lips. I didn't know that by the time I was sixteen it would be the global economy and there would be no summer jobs, even though you did your life-skills analysis as recommended by the guidance counsellor at school. Motivated! Energetic! Computerliterate! Shows initiative! Workplace- appropriate hair! What I never imagined was that by the time I got to be sixteen, the only job you could get would be babysitting. I sometimes take care of my cousin, Laurence. Laurence likes impersonating trucks and being held upside down. I am good at assisting during these activities. This evidently counts as work-related experience. Girls are different. Elizabeth, who calls herself Ib, is six and one-quarter years old. I go over to her place at 7:30 in the morning and I finish at one o'clock. Then her dad or her mom or her gran (who is not really her gran but the mother of her dad's ex-wife) takes over. Ib has a complicated family. She doesn't seem to mind. Ib has a yellow plastic suitcase. In the suitcase are Barbies. Ib would like to play with Barbies for five and one-half hours every day. In my babysitting course at the community centre they taught us about first aid, diapering, nutritious snacks, and how to jump your jollies out. They did not teach Barbies. "You be Wanda," says Ib, handing me a nude Barbie who looks as though she is having a bad hair day. I'm quite prepared to be Wanda if that's what the job requires. But once I am Wanda, I don't know what the heck to do. Ib is busy dressing Francine, Laurice, Betty, and Talking Doll, who is not a Barbie at all, but a baby doll twice the size of the Barbies. "What should I do?" I ask. Ib gives me The Look an unblinking stare that combines impatience, scorn, and pity. "Play," she says. When you have sixteen-year-old guy hands, there is no way to hold a nude Barbie without violating her personal space. But all her clothes seem to be made of extremely form-fitting stretchy neon stuff, and I can't get her rigid arms with their poky fingers into the sleeves. Playing with Barbies makes all other activities look good. The study of irregular French verbs, for example, starts to seem attractive. The board game Candyland, a favourite of Laurence and previously condemned by me as a sure method of turning the human brain into tofu, starts to seem like a laff-riot. I look at my watch. It is 8:15. The morning stretches ahead of me. Six weeks stretch ahead of me. My life stretches ahead of me. My brain is edging dangerously close to the idea of eternity. I hold Wanda by her hard, claw-like plastic hand and think of things that Laurence likes to do. We could notch the edge of yogurt lids to make deadly star-shaped tonki for a Ninja attack, but somehow I don't think that's going to cut it with Ib. She's probably not going to go for a burping contest, either. A warm breeze blows in the window a small wind that probably originated at sea and blew across the beach, across all those glistening, slowly browning bodies, before it ended up here, trapped in Barbie World. I'm hallucinating the smell of suntan oil. I need to get outside. I do not suggest a walk. I know, from Laurence, that "walk" is a four- letter word to six-year-olds. Six-year-olds can run around for seventy-two hours straight, but half a block of walking and they suffer from life- threatening exhaustion. I therefore avoid the W-word. "Ib, would you like to go on an exploration mission?" Ib thinks for a moment. "Yes." We pack up the Barbies. "It's quite a long walk," I say. 'We can't take the suitcase." "I need to take Wanda." We take Wanda. We walk along the overgrown railway tracks out to the edge of town. Ib steps on every tie. The sun is behind us and we stop every so often to make our shadows into letters of the alphabet. ("And what sort of work experience can you bring to this job, young man?" "Well, sir, I spent one summer playing with Barbie dolls and practicing making my body into a K." "Excellent! We've got exciting openings in that area.") We follow the tracks as the sun rises high in the sky. Ib walks along the rail holding my hand. My feet crunch on the sharp gravel and Ib sings something about chicks. I inhale the dusty smell of sunbaked weeds, and I'm pulled back to the summer when we used to come out here, Jeff and Danielle and I. That was the summer that Jeff was a double agent planning to blow up the enemy supply train. The sharp sound of a pneumatic drill rips through the air, and Ib's hand tightens in mine. 'What's that?" I remember. "It's just a woodpecker." There was a woodpecker back then, too. "Machine gun attack!" yelled Jeff. And I forgot it was a game and threw myself down the bank into the bushes. Jeff laughed at me. '"No lit-tle ducks came swim-ming back. "Ib's high thin voice is burrowing itself into my brain, and there is a pulse above my left eye. I begin to wish I had brought something to drink. Maybe it's time to go back. And then we come to the stream. I hear it before I see it. And then I remember what happened there. Ib jumps off the track and dances off towards the water. I don't want to go there. "Not that way, Ib." "Come on, Ken. I'm exploring! This is an exploration mission. You said." I follow her. It's different. The trees dusty, scruffy-looking cottonwoods have grown up, and the road appears too soon. But there it is. The stream takes a bend and disappears into a small culvert under the road. Vines grow across the entrance to the drainage pipe. I push them aside and look in. A black hole with a perfect circle of light at the end. It's so small. Had we really walked through it? Jeff and Danielle and finally me, terrified, shamed into it by a girl and a double-dare. I take a deep breath and I'm there again. That smell. Wet and green and dangerous. There I was, feet braced against the pipe, halfway through the tunnel at the darkest part. I kept my mind up, up out of the water where Jeff said blackwater bloodsuckers lived. I kept my mind up until it went right into the weight of the earth above me. Tons of dirt and cars and trucks and being buried alive. Dirt pressing heavy against my chest, against my eyelids, against my legs which wouldn't move. Above the roaring in my ears, I heard a high snatch of song. Two notes with no words. Calling. I pushed against the concrete and screamed without a sound. And then Jeff yelled into the tunnel, "What's the matter, Kenny? Is it the bloodsuckers? Kenton, Kenton, where are you? We vant to suck your blood." Jeff had a way of saying "Kenton" that made it sound like an even finkier name than it is. By this time I had peed my pants, and I had to pretend to slip and fall into the water to cover up. The shock of the cold. The end of the tunnel. Jeff pushed me into the stream because I was wet already. Danielle stared at me and she knew. "Where does it go?" Ib pulls on my shirt. I'm big again. Huge. Like Talking Doll. "It goes under the road. I walked through it once." "Did you go to that other place?" "What other place?" Ib gives me The Look. "Where those other girls play. I think this goes there." Yeah, right. The Barbies visit the culvert. Ib steps right into the tunnel. "Come on, Kenton." I grab her. "Hey! Hold it. You can't go in there. You'll... you'll get your sandals wet. And I can't come. I don't fit." Ib sits down on the gravel and takes off her sandals. "I fit." Blackwater bloodsuckers. But why would I want to scare her? And hey, it's just a tunnel. So I happen to suffer from claustrophobia. That's my problem. "Okay, but look, I'll wait on this side until you're halfway through and then I'll cross the road and meet you on the other side. Are you sure you're not scared?" Ib steps into the pipe and stretches to become an X. "Look! Look how I fit!" I watch the little X splash its way into the darkness. "Okay, Ib, see you on the other side. Last one there's a rotten egg." I let the curtain of vines fall across the opening. I pick up the sandals and climb the hill. It's different, too. It used to be just feathery horsetail and now skinny trees grow there. I grab onto them to pull myself up. I cross the road, hovering on the centre line as an RV rumbles by, and then I slide down the other side, following a small avalanche of pebbles. I kneel on the top of the pipe and stick my head in, upside down. "Hey, rotten egg, I beat you." Small, echoing, dripping sounds are the only answer. I peer into the darkness. She's teasing me. "Ib!" Ib, Ib, Ib the tunnel throws my voice back at me. A semi-trailer roars by on the road. I jump down and stand at the pipe's entrance. My eyes adjust and I can see the dim green o at the other end. No outline of a little girl. A tight heaviness grips me around the chest. "Ibbie. Answer me right now. I mean it," I drop the sandals. She must have turned and hidden on the other side, just to fool me. I don't remember getting up the hill and across the road, except that the noise of a car horn rips across the top of my brain. She isn't there. Empty tunnel. "Elizabeth!" She slipped. She knocked her head. Child drowns in four inches of bath water. I have to go in. I try walking doubled over. But my feet just slip down the slimy curved concrete and I can only shuffle. I drop to my hands and knees. Crawl, crawl, crawl, crawl. The sound of splashing fills my head. Come back, Elizabeth. Do not push out against the concrete. Just go forward, splash, splash. Do not think up or down. Something floats against my hand. I gasp and jerk upwards, cracking my head. It's Wanda. I push her into my shirt. My knee bashes into a rock, and there is some sobbing in the echoing tunnel. It is my own voice. And then I grab the rough ends of the pipe and pull myself into the light and the bigness. Ib is crouched at the edge of the stream pushing a floating leaf with a stick. A green light makes its way through the trees above. She looks at me and sees Wanda poking out of my shirt. "Oh, good, you found her. Bad Wanda, running away." My relief explodes into anger. "Ib, where were you?" "Playing with the girls." "No, quit pretending. I'm not playing. Where were you when I called you from this end of the tunnel? Were you hiding? Didn't you hear me call?" "Sure I heard you, silly. That's how they knew my name. And I was going to come back but it was my turn. They never let me play before but this time they knew my name and I got to go into the circle. They were dancing. Like ballerinas. Except they had long hair. I get to have long hair when I'm in grade two." My head is buzzing. I must have hit it harder than I realized. I hand Wanda to Ib and grab at some sense. Why didn't you come when I called you?" 'They said I wasn't allowed to go, not while I was in the circle, and they were going to give me some cake. I saw it. It had sprinkles on it. And then you called me again but you said 'Elizabeth.' And then they made me go away." Ib blows her leaf boat across the stream. And then she starts to sing. "Idey, Idey, what's your name, What's your name to get in the game?" The final puzzle piece of memory slides into place. That song, the two-note song. The sweet high voice calling me in the tunnel. The sound just before Jeff called me back by my real name. They wanted me. They wanted Ib. I begin to shiver. I find myself sitting on the gravel. The stream splashes its way over the lip of the pipe into the tunnel. I stare at Ib, who looks so small and solid. My wet jeans with their slime-green knees begin to steam in the sun. A crow tells us a thing or two. "Ken?" "Yes?" "I don't really like those girls." "No, they don't sound that nice. Do you want to go home?" "Okay." I rinse off my hands and glance once more into the darkness. "Put on your sandals, then." Ib holds onto the back belt loops of my jeans, and I pull her up the hill, into the sunshine.