1 - Universiti Teknologi Malaysia

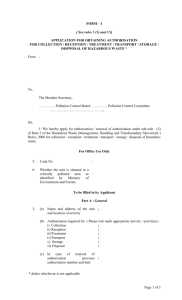

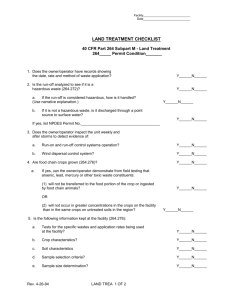

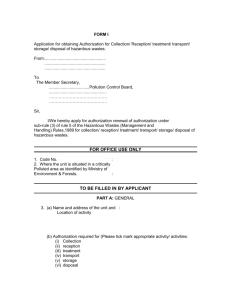

advertisement