Population Growth and its Impact on Maternal Health

advertisement

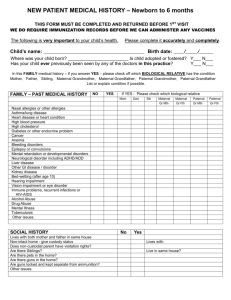

Population Growth and its Impact on Maternal Health The fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG) calls for improvements in maternal health, by reducing maternal mortality by three quarters. The current essay will argue that unless substantial efforts are taken towards lowering fertility rates that will then impact population growth, attempts to achieve this goal are compromised. I will provide evidence pertaining to the effect of population growth on maternal health by focusing specifically in sub-Saharan Africa, where most of the maternal deaths occur, and where the danger of failure to achieve this goal is the greatest. I will provide examples from available research in the field, and will include my own personal experience as a practicing public health physician in Angola. Despite the efforts to bring maternal health to the forefront of public health concerns, the desired improvements have not been achieved. In sub-Saharan Africa, most countries experienced on average no changes in the percentage of deliveries assisted by a skilled attendant1 [figure 1], and show no signs of achieving the scheduled reduction in maternal mortality2. Several reasons for the lack of success so far can be named, but two stand out and are directly related to population growth: current focus on delivery practices and failure to meet the demand for family planning. Most of the current focus on decreasing maternal mortality is on increasing skilled attendants at birth, which involves multifaceted problems. The presence of skilled attendants at birth is conditional on the number of skilled providers and or health care facilities available, and on many socio-cultural factors associated with the delivery process. With a rapid growing population as in the case of sub-Saharan Africa, concurrent substantial improvements on education would have to take place, as well as expansion of the health care infrastructure. Both education and health care are highly linked to economic growth. No country, with the exception of a small number of oil-rich states, has achieved significant economic development while still maintaining high fertility. This means that neither the educational systems nor the health services can be constructed until birth rates decline. The reason for this is the dependency factor: governments of countries in which each cohort of children is followed by a larger cohort, year after year, find it impossible to catch up with the need for education and health services. According to the WHO, Africa’s burden of disease represents 25% of the world’s burden, but its health care workforce constitutes only 1.5%3. Most of the countries in sub-Saharan Africa have lower health care worker density than what is considered reasonable, 2.5/1,000 population. The WHO estimates that it will take on average 20 years for most 1 Abouzar and Wardlaw, 2001. Maternal mortality at the end of a decade: signs of progress?. Bull World Health Organ 79(6):561-8. 2 Koblinsky, 2003. Reducing maternal mortality: learning from Bolivia, China, Egypt, Honduras, Indonesia, Jamaica, and Zimbabwe. HNP Series, World bank.; MDG Report 2005. 3 WHO, 2004 – Addressing Africa’s health Workforce Crisis: An avenue for action. Paper prepared for the high level forum on MDGs, Abuja, Dec. 2004. 1 African countries to achieve significant increases in the needed health care work force, and this is if substantial investments on a large scale are made now. The insufficient number of health care professionals in sub-Saharan Africa is further exacerbated by the fact that the existent work force would like to leave the continent, as measured by intention to migrate4 [figure 2]. African governments have also to deal with health professional’s retention difficulties in rural areas. Even those originally from rural areas, would prefer to leave and work in urban areas after finishing school. Young women for example, after attending high school and some sort of health care training, do return to their villages. However, when they are married and have children, with educational opportunities they need not available in rural areas, they tend to move and settle in urban areas. The socio-cultural factors are more difficult to address. Delivery is perceived as a natural process in life and not a medical condition. Women have been delivering at home with traditional birth attendants in Africa for as long as we have existed. For example, my mother delivered me at home with the assistance of a birth attendant. When trying to understand why women even in urban areas deliver at home, my mother’s response echoes those of many women whose births I assisted during almost 10 years of clinical practice in Angola. Western delivery service models are too strict and do not accommodate the presence of family members during delivery, and therefore the possibility of performing rituals and ceremonies. In addition, women tend to perceive maternal mortality in health care facilities to be high, and rightly so5. The practical solution for the moment in maternal health, while countries are struggling to improve health care systems, is to train existing traditional birth attendants to provide better care, by providing them with the necessary knowledge, low cost and easy to use available technology (and specifically misoprostol tablets for postpartum hemorrhage, the leading cause of maternal mortality), and set up a good referral system, so that only the complicated cases are referred. This might sound as a harsh, dismissive, and hopeless conclusion for maternal health in poor settings. I do consider settling for the lowest possible care an injustice to safe motherhood. However, my conclusion comes from personal experience, when as a young physician in Angola I was sent to complete my two-year community service to a 200,000 population. My public health priorities were maternal and child health, but as the only doctor I soon realized that after seven years in medical school I could not by myself make an impact on the health of the population I was serving. The only strategy was to focus on a very few achievable interventions that could be delivered on a large scale, and to trust and count on the community’s own existing non-professional sector in health care6. I used traditional birth attendants to improve safe delivery practices; community volunteers to recruit, distribute and teach the use of contraceptives, immunization, and the early signs of the most prevalent infectious diseases; and traditional healers to refer to the health center all suspected cases of 4 WHO Migration study, 2003. Facilities tend to receive the most difficult cases; some of them arrive too late, when a life cannot be saved. 6 In this case for maternal health and child health I worked with traditional birth attendants, community volunteers and traditional healers. 5 2 infectious diseases. The same community I served in 1989-1990, with now more than double the population7, has still only one health center, and for the last 5years it has had no doctor. The non-professional health sector is entirely responsible for the health of the community. Most countries where maternal mortality is the highest are not implementing effective interventions on a large scale, such as the provision of family planning and safe abortion. The beneficial public health impact of these interventions is well known, and so is their impact on reducing population growth and improving maternal health. There is an enormous and well documented unmet need for family planning in the developing world [figure 3]. About 150 million married women in developing countries want to delay or avoid pregnancy but are not using contraceptives. Each pregnancy multiplies a woman’s chance of dying from complications of pregnancy or childbirth. In settings such as sub-Saharan Africa where most of the women do not have access to basic obstetric care, access to contraception may be a matter of life and death, particularly when presented with risks of an unwanted or unplanned pregnancy. According to the UNFPA, meeting the existing demand for family planning services would reduce pregnancies in developing countries by 20 per cent, and maternal deaths and injuries by a similar degree or more. We also know that as family planning use rises, women’s desired family size declines. When family planning is made easily available, along with the correct information required to make the various methods useful, the population factor is indeed amenable to change. About 13 to 25 per cent of all maternal deaths are attributed to unsafe abortions, coupled with lack of skilled follow-up. The high level of unmet need for quality contraceptive services, along with the corresponding number of unwanted pregnancies, is a key reason why so many women who want to control their fertility seek out abortions. More than one quarter of pregnancies worldwide, about 52 million annually, end in abortion. There is a small difference in abortion rates per 1000 women aged 15-44 between developed and developing countries ( 39/1000 and 34/1000 respectively)8. The large differences lay in the fact that developing country abortions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, are unsafe abortions and many of these results in the death of the woman. In 2005 the UNAIDS estimated that 17.5 million women were living with HIV (one million more than in 2003). Twenty-five percent of them have unmet need for contraception, representing roughly 4.4 million HIV+ women in need of contraception. Family planning is one the most cost-effective ways of preventing mother-to-child transmission9. 7 8 Mostly due to migration Alan Guttmacher Institute, Sharing Responsibilities: Women, Society and Abortion Worldwide. 1999. 9 Reynolds HW, Janowitz B, Homan R, Johnson L. Cost-Effectiveness of Two Interventions to Avert HIV-. Positive Births. Family Health International (FHI). 3 Clearly, a woman’s ability to plan how many children she wants and when she wants them is central to the quality of her life. The ability to control fertility can be given through family planning programs that have an effect on both population size and maternal and child health. Finally, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa have scarce resources for maternal health services, and they lack the necessary capacity to mobilize resources and commitment for these programs. Given the level of poverty prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, most women cannot afford family planning services [Table 1]. However, given the necessary resources, most developing countries can decrease fertility by increasing contraceptive prevalence, while at the same time reducing maternal mortality. In my view, the greatest hope of decreasing maternal mortality in Africa and in poor countries in other regions of the world lies on two fronts: decreasing fertility, and tackling the main cause of maternal mortality, postpartum hemorrhage. Both of these are related to population growth. For a country to have smaller families pays a demographic dividend, opening the door for the government to expand its health infrastructure, and resulting in better parenting and more stable and richer societies, in addition to having significant effects on maternal mortality. Figure 1: Trends in Skilled Attendance at Birth. Source: Millennium Development Goals Repost 2005 4 Figure 2: Intention to Migrate among health care workers in Africa. Source: WHO Migration Report, 2005. 100 % with unmet need 90 % using a method modern contraceptives 80 74 70 62 60 54 52 50 40 28 30 30 25 20 10 9 0 Sub-Saharan Africa Middle East Latin America Asia Figure 3: Unmet need and use of modern family planning services among married women. Source: Data computed by the author using Statcompiler from Demographic and health Surveys (DHS), measuredhs.com. 5 Table 1: Percent Who Cannot Afford Family Planning. full cost 3/4 cost half cost only commodities Sub-Saharan Africa 98 96 93 77 Arab States/E.Europe 65 51 33 10 Latin America 54 44 30 9 Asia 89 82 71 30 all aid-dependent nations 84 76 66 34 Source: Green, R. 2002. Empty pockects: Estimating ability to pay for family planning. Bay Area International Group, University of California, Berkeley. http://big.berkeley.edu/research.workingpapers.atp.pdf 6