Alternative Movements: Organics, Fair Trade and

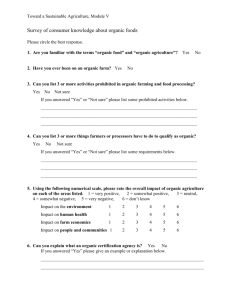

advertisement

Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 Alternative Movements: Organic, Fair Trade and Localism “Conscientious consumption,”1 or making informed, ethical choices when it comes to purchasing food is a growing trend among consumers. Due to increased scientific research and food scares such as the BSE crisis in 1989, many consumers are straying from conventional food products and are looking for alternatives to industrial agriculture. The growing demand for more holistic food choices has led to three alternative movements in consumption – organics, Fair Trade and localism. Organic agriculture was originally intended to provide consumers with an alternative to industrial agriculture. Organic products also have a set of standards to which they must adhere in order to carry the USDA stamp of approval. Fair trade products were also offered as an alternative to industrial products, in addition to supporting low-income farmers in third world countries. The local food movement is the subjective and open-ended of the movements, with no regulation by the federal government or trade organizations. Specifically, local products focus on community sustained food and economy. Together, organics, fair trade and localism offer an alternative to conventional, industrial agriculture. However, as the movement grew in popularity, the alternatives had to grow as well, making necessary changes along the way. Although the alternatives rose from ethical intentions, many people criticize them for becoming gradually less holistic. This paper will analyze each of the three movements, organic, Fair Trade and localism, 1 Laura Raynolds and Michael Long, “Fair/Alternative Trade: Historical and Empirical Dimensions,” Fair Trade: The Challenges of Transforming Globalization. (Routledge: New York, 2007) 16. 1 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 and to what extent they do or do not represent a credible alternative to industrial agriculture. Origins and Appeal of Alternative Movements Julie Guthman discusses “the reflexive consumer” in her article “Fast Food/Organic Food: Reflexive Tastes and the Making of ‘Yuppie Chow’,” which covers the rise of organic products as an alternative to conventional food. She contrasts the “reflexive eater” with the “fast food eater” – “the reflexive consumer pays attention to how food is made, and that knowledge shapes his or her ‘taste’ towards healthier food.”2 According to Guthman, eating organically “tastes better” to consumers because of the informed choices they have made. For example, Guthman notes that organic salad mix is essentially flavorless, but packs an “extra ingredient of desire” when associated with better health and the environment.3 In fact, salad greens were among the first products to be available organically to consumers. Restaurants in California, where the organic movement began, that supported the alternative food movement acquired the salad greens from local farms, advertising them as organically grown to consumers. Guthman explains, “Although organic produce more generally had long been sold in health food stores, co-operatives and selected greengrocers, the taste for organic salad mix was mostly diffused through restaurants, as are many exotic tastes.”4 The appearance of organic products on 2 Julie Guthman, “Fast Food/Organic Food: Reflexive Tastes and the Making of ‘Yuppie Chow’,” Journal of Social and Cultural Geography (Vol. 4, No. 1, 2003) 46. 3 Guthman 54. 4 Ibid 49. 2 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 restaurant menus helped to bring alternative consumption into the mainstream. Because organics opposed conventional products, they were viewed as a high value commodity for the “reflexive consumer.” In a chapter titled, “Fair/Alternative Trade: Historical and Empirical Dimensions,” Laura Raynolds and Michael Long explain that the Fair Trade movement originally grew from North American and European Alternative Trade Organizations. The ATOs sought to help impoverished groups of people in third world countries by creating an alternative trade network. Instead of direct aid to poorer, low-income countries, Fair Trade seeks to help them through trade and support for their economies. Low-income farmers involved with Fair Trade benefit from fairer prices for their products and also access to stable markets such as those of the United States. In addition, ATO’s work to teach consumers how to make ethical purchases, and why buying conventionally trading products can hurt lowincome farmers.5 Raynolds and Long write that Fair Trade practices can “promote alternative values and practices of fairness, partnership and respect [and] can ‘shorten the distance’ between consumption and production in global arenas.”6 Through establishing trading links between North American and third world countries, the main draw of Fair Trade to consumers is access to greater knowledge about the producer and also the notion that their purchase will benefit that producer. 5 6 Raynolds and Long 15. Ibid 18. 3 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 Patricia Allen and Clare Hinrichs address the appeal of the local movement in their piece, “Buying into ‘Buy Local’: Engagements of Unites States Local Food Initiatives,” a chapter in the book Alternative Food Geographies. The growth of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), or buying products from local farmers, has become another alternative food movement among consumers. CSAs involve a community pledging to support local farms by buying a share of their crops. Allen and Hinrichs write, “Fresh, local food is a vision that unites community food security activists, environmentalists and small scale farmers globally.”7 Similar to the Fair Trade movement, buying products locally fosters a connection between the producer and the consumer within a community. In addition to CSAs, another group called Community Involved in Sustaining Agriculture (CISA) supports local farmers by creating “Buy Local” campaigns to educate and sway consumers towards localism.8 “Buy Local” campaigns encourage a “buycott” among consumers, convincing them to purchase only local products with qualities and attributes they support. The Local Food movement appeals to consumers because they believe products are fresher, better tasting and more environmentally friendly than conventional products. Also, local food is regarded so highly because consumers are can learn the name of the farm from where their food comes and even the name of the farmer who grows it. Consumers also support environmental benefits of local 7 Patricia Allen and Claire Hinrichs, “Buying into ‘Buy Local:’ Engagements of United States Local Food Initiatives,” Alternative Food Geographies: Representation and Practice (Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, United Kingdom, 2007) 255. 8 Allen and Hinrichs 258. 4 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 food, such as preserving the biodiversity of farmland and encouraging a sustainable community.9 Are the Alternatives still “Alternatives?” Initially, organics, Fair Trade and localism were alternatives to industrial agriculture because they tried to remain small, focusing on building a relationship with the consumer. However, producers are quickly realizing that as the alternative movement continues to grow in popularity, demand for their products must increase. To keep up, many producers have had to make adjustments, in some cases acquiring attributes of industrial agriculture. Critics such as Michael Pollan, in his book The Omnivore’s Dilemma, questions whether these alternative movements should still be considered “alternative.” Pollan focuses on the recent industrialization of organic products, criticizing the movement for “coming a long way in the last 30 years, to the point where it now looks considerably less like a movement than a big business.”10 He brings up the issue of a mostly-organic grocer, Whole Foods, as an example of what he calls “the organic empire.” He explains that the store is aware of the contradictions they project, and how they have tried to mask the image of organic industrialization. Pollan believes that the organic movement has lost its original focus in the midst of consumer demand and the potential for increased profits. For example, large organic providers such as Whole Foods have taken advantage of labeling to 9 Ibid 260. Micahel Pollan, The Omnivore’s Dilemma (Penguin Books: New York, 2007) 138. 10 5 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 grab the attention of “conscientious consumers.” Pollan uses the example of “Rosie the Organic Broiler Hen,” The label also ensured that the hen was “sustainably farmed” and “free range,” even listing the name of the farm from where she came. If that wasn’t enough, the label included the farm’s vision – “Petaluma Poultry, a company whose ‘farming methods’ strive to create harmonious relationships in nature, sustaining the health of all creature and the natural world.”11 Consumers look for “organic” and other related comfort words, believing they are making a well-informed, ethical purchase. However, Pollan informs that labels can be manipulative, misleading consumers into making a purchase. After visiting Rosie’s “home,” Petaluma Poultry, he discovers that that farm is more like an “animal factory.” He describes Rosie’s life with contempt – “She lives in a shed with twenty thousand other Rosie’s, who, aside from their certified organic feed, live lives little different from that of any other industrial chicken…the freerange story seems a bit of a stretch when you discover that the…little door in the shed leading out to a narrow grassy yard…remains firmly shut until five or six weeks old…[and] are slaughtered only two weeks later.”12 Pollan criticizes Whole Foods for subtly advocating the globalization of organic products. He reports that most of Whole Food’s produce comes from two big farms in California, Earthbound Farms and Grimmway Farms. Pollan describes Whole Foods as “selling a connected, holistic ensouled product through a Western, reductionist, Wall Street sales scheme”13 and are no different than Wal-Mart. To 11 Pollan 135. Ibid 140. 13 Ibid 248. 12 6 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 keep up with increasing demand, Whole Foods must buy from larger farms to maintain a profit. The Fair Trade movement is also affected by growing popularity and demand among “conscientious consumers.” Raynolds and Long write that as non-ATO businesses look into Fair Trade opportunities, maintaining public trust that ATOs promote is becoming more difficult. As a result, the need for stricter certification processes and specific labeling is necessary to ensure credible Fair Trade products.14 The Fairtrade Labeling Organization (FLO), another sector of the movement, has taken responsibility for certification and labeling of larger mainstream businesses. Raynolds points out that the problem with this system is that Fair Trade’s initial emphasis on the relationship between consumers and producers is made meaningless– “Labeling organizations communicate with producers largely indirectly through the implementation of certification standards and procedures; communication with consumers is similarly indirect and is essentially reduced to a small product sticker.”15 Raynolds and Long describe the FLO labeling system as increasingly bureaucratic and industrialized, a shift from the ATO’s orginal vision of a small, alternative movement. As a movement, Raynolds foresees Fair Trade as creeping towards Pollan’s definition of the “Organic Industry.” Better yet, this may be inevitable, as big businesses such as Starbucks take over Fair Trade from ATOs.16 14 Raynolds and Long 18. Ibid19. 16 Ibid 24. 15 7 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 Because localism is not regulated by the government or trading organizations, faces a different set of problems than organic or Fair Trade. The CISA’s “Buy Local” campaign advocates the benefits and value of buying local to consumers, focusing mostly on economic, environmental and community benefits of localism. However, Paul Roberts, in his book The End of Food, presents a different perspective on the local food movement. According to Roberts, what “Buy Local” campaigns tell consumers may not be completely accurate in terms of environmental and economical benefits. The campaigns claim that because local food saves energy because it travels less distance from the farm to the consumer. Roberts asserts that just because food covers less miles from producer to consumer does not mean it is more sustainable energy wise. He states that food transportation costs are actually less for most industrial foods – “A semi driving several tons of produce 312 miles from a mega-farm in the Salinas Valley to a Wal-Mart in Reno may seem an egregious waste of energy, but it actually buns less fuel than would the dozens of pick-up trucks needed haul the same quantity of produce to a farmers market in Reno from local farms just 20 miles away.”17 If Robert’s claims are true, then “Buy Local” campaigns are providing consumers with misleading information. Another problem with localism that Roberts outlines is the challenges that small farmers and producers lack the money and resources to be long-term contributors to the US food supply. Although small farmers as a contributor to the food supply in the US is growing, Roberts reports that they still make up only 10% of the overall supply. The rest of the supply is provided by industrialized, mass17 Paul Roberts, The End of Food (Houghton Mifflin Company: New York, 2008) 285. 8 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 producing food companies. Allen and Hinrichs state that many alternative food system activists believe that localism can lead to “environmental, economic and social change in the agri-food system.”18 However, Roberts asserts that it is unrealistic that the efforts of small, local farmers can change an industrial food system that sustains the majority of US population. A recent article in the Baltimore City Paper by Michelle Gienow asserts that the power to change the industrial food system lies in the hands of consumer. She encourages readers – “With each food dollar spent, we are all casting an essential vote. You can't buy a senator, the way the agribusiness lobbyists can, but you can say yes to locally grown tomatoes.”19 Gienow evokes the “buycott” idea through her experiment, where she attempts to purchase and prepare only “SOLE,” or sustainable, organic, local and ethical foods for her family for one month on a Food Stamps budget. She discovers that it is more difficult than she expected to survive entirely on “SOLE” foods, as they tend to be more expensive and difficult to obtain than conventional products. Through creative preparation and effort, Gienow finds a way to feed and please her family, even her young children, through CSA deliveries of fresh produce, bulk buys of brown rice and fair trade, shade grown coffee. Instead of buying her children’s favorite conventional cereal, “Joe’s O’s,” she tries something new, oatmeal with rolled oats and honey, all of which are less expensive than the cereal. Gienow encourages readers to make the same changes. 18 Allen and Hinrichs 263. Michelle Gienow, “SOLE Food: Eating Organically (and Sustainably) on a FoodStamp Budget.” The Baltimore City Paper. 7 October 2009. 20 November 2010 <http://www2.citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=19079>. 19 9 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 The Future of Organic, Fair Trade and Localism As the notion of “conscientious consumption” continues to grow, it is clear that changes will need to be made to the organic, Fair Trade and local movements to accommodate increasing consumer demand. Pollan may be right in his assertion that the movements are losing their original focus in the process, and are less “alternative” than before. Gienow’s idea of “buycotting” “SOLE” products is a step in the right direction. Yet even if her idea is followed by consumers, and support for “SOLE” increases, there is still Robert’s problem of the small, local farmer versus the demands of the US food supply. He proposes that the best output for “SOLE” food is not small farmers, but midsize farmers instead. Medium sized farms, usually between 50 and 500 acres, are large enough to produce a reasonable amount of food at an affordable cost. Mid-size farmers can still monitor their crops acre by acre to ensure ethical practices. However, Roberts reports that the majority of farms in existence are either large-scale industrial farms or small, locally based farms.20 To institute Gienow’s ideas, Roberts believes that the future expansion of “SOLE” food is possible through the increase of medium sized farms. Organics, Fair Trade and localism do not necessarily have to stay “small” to be successfully influential movements, as Roberts points out. His ideas show that as organics, Fair Trade and localism move more towards the mainstream, they must find a way to adjust their original visions to fit increased consumer demand while maintaining their integrity. 20 Roberts 280. 10 Elizabeth Laseter Food Politics 11/23/10 Bibliography Roberts, Paul. The End of Food. Houghton Mifflin Company: New York, 2008. Allen, Patricia and Claire Hinrichs. “Buying into ‘Buy Local:’ Engagements of United States Local Food Initiatives.” Alternative Food Geographies: Representation and Practice. Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, United Kingdom, 2007. Pollan, Micahel. The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Penguin Books: New York, 2007. Raynolds, Laura and Michael Long. “Fair/Alternative Trade: Historical and Empirical Dimensions.” Fair Trade: The Challenges of Transforming Globalization. Routledge: New York, 2007. Guthman, Julie. “Conventionalizing Organic.” Agrarian Dreams: The Paradox of Organic Farming in California. University of California Press: Berkeley. 2004. Guthman, Julie. “Fast Food/Organic Food: Reflexive Tastes and the Making of ‘Yuppie Chow’.” Social and Cultural Geography, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2003): 45-58. Gienow, Michelle. “SOLE Food: Eating Organically (and Sustainably) on a FoodStamp Budget.” The Baltimore City Paper. 7 October 2009. <http://www2.citypaper.com/news/story.asp?id=19079>. 11