New protocol may improve safety of waste disposal at the nation`s

New protocol may improve safety of waste disposal at the nation’s landfills

By Emily Waltz

February 11, 2002

In 1997, dangerously high levels of arsenic and cyanide were found in the groundwater in

Gum Springs, Arkansas near the Reynolds Metals Company landfill. The discovery surprised both Reynolds – the manufacturer of Reynolds Wrap and other popular household products – and the Environmental Protection Agency. EPA’s recommended testing procedure, which the company had followed, had given a green light to a proprietary method for disposing of aluminum wastes that Reynolds had developed. Unfortunately, the results of EPA’s test were wrong.

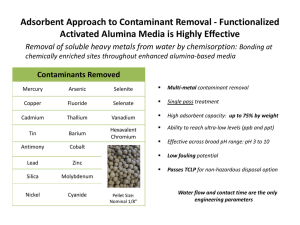

David Kosson, chairman of environmental and civil engineering and professor of chemical engineering at Vanderbilt, has developed a strategy that could prevent such surprises in the future. Kosson and his team have designed a protocol that can more accurately predict the chemical reactions that will result when different kinds of wastes are mixed in a given landfill.

Kos son’s protocol has been accepted for publication by the journal Environmental Engineering

Science and EPA officials are considering adopting it as a supplement to their current procedures.

“This project was started in response to a perceived need,” Kosson says. “The current approach is inadequate, misleading and results in unnecessary environmental impact and wasted resources. I think the new approach will make a great difference.”

EPA officials have acknowledged some of the criticisms of the current testing procedure and are looking for alternatives. “We believe the framework Dr. Kosson developed has considerable promise as an alternative to our default test, the TCLP, in certain circumstances,” states EPA’s Greg Helms, an environmental protection specialist in the Office of Solid Waste.

Kosson has been working with the EPA and specifically with Helms for the last few years on the project.

When it rains, chemicals from various wastes in landfill combine

When it rains, chemicals from solid waste combine with other constituents in the landfill.

As the water percolates down through the landfill, it can bring chemicals from different areas together to form potentially dangerous chemical combinations. This contaminated rainwater, called leachate, flows to the bottom of the landfill, which typically is lined with alternating layers of

- 1 -

Toxic waste test Page 2

clay and plastic. But such a lining is somewhat permeable, allowing the leachate to seep into the groundwater below.

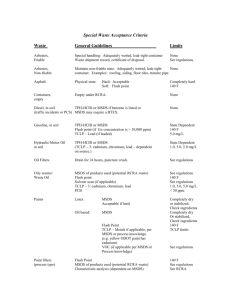

To minimize the danger of the chemicals that get through the liner, the EPA mandates that companies conduct a test before adding a new type of waste to the landfill. The test simulates the content and conditions of the landfill and predicts the potential chemical reactions that could occur when the new waste is added to the existing waste. The test, called the Toxicity

Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP), was designed in 1986 and is the EPA’s standard system for evaluating the safety of adding all types of solid waste to municipal sites.

According to Kosson and his team, TCLP is generic. It was designed to simulate an average municipal landfill and does not take normal variations in conditions into account, including differences in chemical content, acidity, liquid-to-solid ratio, and age. The fact that most waste currently being tested is not destined for municipal landfills also raises questions about

TCLP’s applicability.

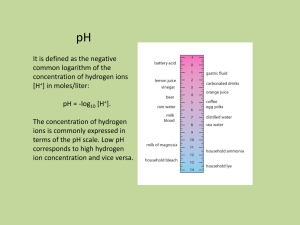

Current test does not take account of local factors like acidity

The Reynolds landfill, for example, had an unusually high pH level – a factor that the

TCLP test does not take into account. Although the materials Reynolds discarded were considered non-hazardous, they reacted under extremely basic (pH) conditions differently than the TCLP had predicted. When Reynolds tested the composition of the leachate under the landfill, they found that the level of arsenic was 100 times higher than the TCLP test had estimated, according to Helms.

By using a more sitespecific approach, Kosson’s alternative procedure can simulate a range of landfill conditions, including factors such as pH level. “TCLP tests are done under only one set of circumstances. Kosson’s protocol adapts to particular circumstances,” says Helms.

In addition to underestimating risk, the TCLP test can also overestimate the potential hazard involved in adding certain wastes to landfills. The Resource Conservation and Recovery

Act requires EPA to classify waste as either hazardous or non-hazardous. Management and disposal of waste that is deemed “hazardous” requires more protective handling and disposal, and costs roughly ten times more than “non-hazardous” waste, Helms says. So, if the TCLP test mistakenly predicts that addition of a given waste will produce hazardous leachate, it can drive up a companies disposal costs significantly.

Several companies have challenged the EPA for over-regulation of waste disposal

Several companies have challenged the EPA for over-regulation of waste disposal caused by TCLP estimates. In April 2000, the Utility Solid Waste Activist Group (USWAG) challenged the validity of the TCLP in the lawsuit Association of Battery Recyclers v. EPA .

Several companies wanted to clean up old manufactured gas plants that had been abandoned in

Toxic waste test Page 3

the early 1900’s. USWAG, which initiated the suit, contended that the TCLP was not accurate for the non-municipal landfills in which companies planned to discard the gas plant wastes.

“You need to tailor a test to the specific waste disposal site. The TCLP isn’t going to tell you much about the sites where municipal gas plant waste is discarde d,” says Jim Roewer, executive director of USWAG.

The court agreed with USWAG. It concluded that the TCLP test could not determine the toxicity of gas plant waste in those landfills and ruled that the EPA may not apply the TCLP test to manufactured gas plant sites. Companies then relied on test methods required by state regulations rather than the EPA, and saved an average of $65,000 in clean-up costs per site.

New test procedure costs more but would provide substantial cost savings in long run

In the document describing the protocol submitted to Environmental Engineering

Science , Kosson argued that the more accurate estimates it will provide will both improve environmental protection and economic efficiency as well. The new testing approach will cost more than the TCLP, but using a more accurate test will bring companies substantial cost savings in the long run by eliminating unnecessary or inappropriate measures of waste clean-up. At the same time, if the production of dangerous contaminants in the landfill is a real possibility, the new test will provide more accurate estimates, allowing companies to adopt procedures that will avoid costly accidents like the Reynolds’ case.

Still, many companies still support use of the TCLP because of its simplicity. “Companies just want an answer : ‘yes’ or ‘no,’” explained Florence Sanchez, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Vanderbilt who works with Kosson on the protocol. She says that

Kosson’s research group would like to make the test as accurate as possible, but the more detailed the test, the more time consuming and expensive. “That’s why companies like the TCLP.

It’s as simple as you can get,” she says.

EPA’s Helms has recognized the need for the new procedure and is helping Kosson move the protocol through the difficult process of gaining official EPA sanction . “We are quite encouraged by the protocol’s pending publication. With detailed protocols published, we hope to begin work on some “next steps” with Dr. Kosson, primarily conducting some field validation studies at actual waste disposal facilities,” says Helms.

But in between publishing and field work, Kosson and the EPA will need funding. They are looking toward large groups that would benefit from the new testing approach. Prospective funding partners include the Federal Highway Administration, the Department of Energy, and individual states, Helms says.

-VU -