Sample 7 - North Carolina State University

advertisement

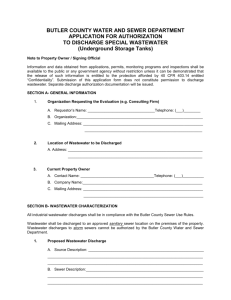

The “Second Time Around”: Can Wastewater Have a Productive Life as “Reclaimed Water”? Imagine that the water spitting out of sprinkler systems on lawns, public parks, roadway medians, and golf courses originally came from somebody’s toilet. Welcome to St. Petersburg, Florida. Welcome to south San Francisco Bay. Welcome to Phoenix. Welcome to Raleigh? In densely populated, water-strapped cities in places like Florida, California and Arizona, treated wastewater, or “reclaimed water,” is a daily reality. In an effort to conserve sources of potable water, or freshwater suitable for needs such as drinking, cooking and bathing, these cities use reclaimed water for irrigation, street washing, or industrial cooling. The noisy ticking of a sprinkler is a constant reminder that reclaimed water is helping to conserve precious freshwater resources. In a state like North Carolina, where water resources currently seem plentiful, the notion of putting water that was once in our toilets, bathtubs and sinks on lawns may seem ridiculous, if not disturbing. But as politicians debate the validity of global warming and forecasters around the nation hint at the possibility of yet another hot and dry summer, the consequences of the Triangle’s unrelenting growth and development come into sharp focus: Its constant demand for freshwater is causing increased strain on the region’s potable water resources. On any given day, Wake County residents are likely to use more freshwater to flush their toilets and wash their hands than they use for drinking. But after they’ve flushed their toilets and turned off their faucets, the water they’ve used is far from being gone. Instead, it is funneled to 1 one of the publicly owned wastewater treatment plants where it is treated and then discharged into local waterways such as the Neuse River. Traditionally, officials have viewed the wastewater slipping down the drains of more than 240,000 Wake County households as troublesome byproduct of progress ─ to be disposed of as quickly and efficiently as possible. But as Wake continues to grow, increasing amounts of both residential and industrial wastewater mean that cities and towns must worry about pushing up against their state-allocated discharge permit limits (See related story: Abuse of the Neuse?), forcing county and city officials to begin exploring more innovative strategies for long-term wastewater management, including water reclamation. Rethinking Wastewater “More and more municipalities are looking at re-use,” says Dr. Bob Rubin, professor of agricultural engineering at North Carolina State University. Re-use can significantly reduce the per capita consumption of freshwater and help wastewater facilities stay in compliance with their permit limits for nutrient discharge, he says. In fact, the 1998 Wake County Water/Sewer Plan identified water reclamation as one of its key tools for its water and sewer management strategy. Many communities in the Triangle have already started to explore reclaimed water systems: The town of Cary operates two reclaimed water systems that pump approximately five million gallons of highly treated wastewater per day for reuse customers that include John Deere and WorldCom. The majority of Cary’s reclaimed water customers are located near the two treatment facilities, and the town delivers reclaimed water to its customers via a separate, intricate piping system that runs parallel to potable water lines. 2 And the City of Raleigh is exploring an expansion of its water reclamation system, which is currently limited to irrigating a field near the Neuse River Wastewater Treatment facility. The city is working with Black and Veatch, an international consulting company, to prepare a master plan for a future reclaimed water system. Such a plan could include infrastructure similar to the city’s drinking water master plan, which contains over more than 1,300 miles of water mains and 1,500 miles of sewer mains. But laying enough pipes from the plant to the furthest reaches of the city could take almost 40 years at variable expense, says Tim Woody, the reuse superintendent. “Obviously, getting reused water to certain sections [of the city] will be cheaper,” he says, citing businesses and industry near the Neuse River Treatment Plant. “Getting it to someplace like Carter-Finley Stadium, some 20 miles away, would be more expensive.” But given the considerable expense of following the footprint of the drinking water master plan, the city is exploring alternative technologies for a reclamation system, including water-scalping units, which create and distribute reclaimed water much closer to potential customers. Common in dry regions like California and Arizona, scalping units are attached to existing pump stations and function like mini-wastewater treatment plants: they take in wastewater from the pump station and treat it to reuse standards using biological or chemical processes. Ultimately, the scalping unit has the potential to produce reclaimed water closer to customers needing non-potable water for purposes such as irrigation and industrial cooling. “We’d be taking the treatment mechanisms to the market,” says Woody. 3 Public Skepticism and Concern Experts say that reclaimed water doesn’t smell or look any different than potable water, but it is unlikely that Triangle residents will ever find it coming out of their faucets or showerheads. Currently, reclaimed water is not directly reused as drinking water anywhere in the United States, although there has been some controversy in California over the notion of injecting reclaimed water into underground aquifers to help replenish potable water supplies. Instead, reclamation efforts focus on producing non-potable water -- water that isn’t intended to be drinkable but is perfectly suitable for uses such as residential and commercial irrigation. Public skepticism about the mere concept of reclaimed water is likely to run deep, however, especially given the poor image of wastewater treatment technology in the Triangle. Last March, the City of Cary received complaints from residents and I-40 commuters about the stench wafting from the wastewater treatment plant near the Harrison Avenue exit. In June 2002, the public learned about Raleigh’s sludge application debacle: the Neuse River Wastewater Treatment Plant contaminated nearby groundwater by spraying too much sludge, or solids left over from the water treatment process, on adjacent farmland. But perhaps the most damaging blow to the concept of reclaimed water came earlier this year when controversy erupted over placing privately owned, lagoon-and-spray systems in two new eastern Wake County subdivisions that aren’t connected to city water and sewer services. In short, these systems divert human waste to large holding tanks where bacteria digest the solids. The resulting liquid is treated and sprayed on a nearby field that absorbs excess nutrients. The systems are similar to those used in the hog farming industry, but given the spotty environmental history of hog waste lagoons, nearby residents on well water were concerned that 4 the systems could contaminate their groundwater. Due to citizen pressure, the Wake County Board of Commissioners rescinded the developer’s permits for implementing the systems. But it is erroneous to compare municipal reclaimed water systems to spray-irrigation systems like the one at the Neuse River Wastewater Treatment plant or privately owned lagoonand-spray systems, says Kim Fisher, Cary’s public works and utilities director. The standards of treatment are markedly different, he explains. The spray technologies don’t treat wastewater to the same level as does a municipal reclamation system, which uses physical, biological and chemical processes to remove bacteria and microbes, as well as to reduce concentrations of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorous. In fact, the resulting quality of reclaimed water often surpasses that of water drawn from rivers and lakes before it is treated and distributed as potable water, says Tim Woody, the reuse superintendent of public utilities in Raleigh. “One of the greatest challenges in implementing reclaimed water infrastructure and policy is convincing the public that reclaimed water is safe and beneficial,” says Dr. Rubin. Fisher, Cary’s public works and utilities director, says that an extensive and ongoing public relations campaign helps convince many residents that reclaimed water is a prudent measure for conserving water resources. But the public’s initial fear about reused water is simple: It likely originated in someone’s toilet, sink, or shower. And sending waste “away” somewhere is an accepted and almost unquestioned societal practice, says Rubin. Implementing policies and procedures to reuse wastewater asks people to completely rethink their cultural assumptions about waste that have likely been ingrained since birth. 5 Other Alternatives If municipal reclaimed water systems aren’t economically feasible or don’t fly with the public, what about spray-irrigation technologies? The implementation of spray-irrigation technology in Pamlico County’s Bay River Metropolitan Sewerage District a few years ago was hailed as a success for reducing the area’s nitrogen discharge into the lower Neuse River, says Dean Naujoks, Upper Neuse riverkeeper for the Neuse River Foundation, a non-profit citizen’s environmental watchdog group. Currently, privately owned lagoon-and-spray irrigation systems, like those proposed for new subdivisions in Wake County, are developers’ answer to building new communities in rural areas where city water and sewer utilities are not available. If developers keep pushing for the non-discharge lagoon-and-spray systems, an alternative might be to place them under centralized management by local or regional government, Dr. Rubin suggests. Critics of the lagoon-and-spray systems say the systems work in theory-- when they are run on test grounds and under close supervision. “If you do it just right, it works,” says Stan Norwalk, a former member of the Wake County Planning Board and outspoken environmental advocate. “But it takes a lot to do it right.” Ideally, the vegetation on the land is supposed to absorb the excess nutrients, such as nitrogen and phosphorous, from the discharged wastewater. However, the right balance has to be struck among land area, soil type, saturation limits and plant species, says Norwalk, and he is worried that rules and regulations for such systems are insufficient at the county level. “If Wake County were to try and incorporate several such systems into their wastewater management plan, it would need to hammer out some new county regulations and guidelines,” 6 says Norwalk. There are currently no county ordinances regarding wastewater treatment systems that discharge on land aboveground, only state regulations. Besides, Wake County already has thousands of mini wastewater treatment systems in operation, says Norwalk. “They’re called septic systems.” Septic systems are privately owned sewage disposal systems that treat wastewater in a holding tank underground and then leach the effluent into the soil. And septic systems, Norwalk notes, aren’t inspected by the county or state as often as they should be due to staff and money shortages. Norwalk fears that, even under centralized management, inspections of decentralized spray-irrigation systems would also fall by the wayside. Municipal Reclaimed Water Systems Spray-irrigation systems are also limited by how much water a given area of land can absorb, says Dr. Rubin. Once the land is saturated, nutrient-rich water slides off the top ─ much like a paved parking lot on a rainy day ─ and contributes to pollution of local rivers, streams, and lakes. That’s where municipal reclaimed water systems have distinct advantages, says Tim Woody of Raleigh’s public utilities department. Whether these reclamation systems are scalping units or pipes connected to a large municipal reclamation plant, they do not have “a closed loop arrangement” like spray irrigation systems, he explains. Spray systems are forced to discharge on land, but a municipal reclaimed water system’s infrastructure would still allow treated wastewater to be discharged into rivers during a season of heavy rains. Even though the Triangle doesn’t have the added difficulty of an arid climate like states in the Southwest, its increasing population continues to stress potable water supplies, and 7 reclaimed water systems could significantly ease that strain by producing water specifically intended for non-potable uses, such as street washing or watering golf courses and parks. Last summer, the town of Cary was able to reuse approximately 1 million gallons of treated wastewater on days when temperatures climbed and water usage peaked. During 2003 the town reused more than 37 million gallons of water, effectively reducing the amount of potable water used for residential and commercial irrigation, manufacturing processes, and industrial cooling. Besides conserving potable water supplies, widespread use of reclaimed water helps decrease the amount of wastewater effluent that treatment plants discharge into the Neuse River Basin. This reduces pollutants in the waterway and, as the Triangle keeps growing, helps wastewater treatment plants stay in compliance with their permit limits for nutrient discharge into the river. If forecaster predictions of a dry summer are correct, another drought may not be such a bad thing for Wake. Sure ─ reservoirs will shrink, lawns will go brown, and neighbors will report each other for watering on the wrong day. But another drought can could also provide an impetus for leaders to step up the pace of current water reclamation efforts so that both current and future residents can benefit from responsible growth in Wake County. 8 SIDEBAR Water Reuse Technologies Municipal Reclamation Plant Wastewater is piped into a municipal plant where it is put through advanced physical, biological and chemical treatments and then re-distributed using a piping system that often parallels a city or town’s water and sewer master plan. This is the type of system used in the town of Cary. The cost and time associated with laying miles of new pipe from the plant is a common constraint for larger municipalities. Water Scalping Units Attached to existing pump stations, water scalping units function like mini wastewater treatment plants. They remove wastewater from the pump station and put it through advanced physical, biological and chemical treatments. The result is reclaimed water produced much closer to potential customers. Water scalping units were first introduced to North Carolina when Oak Island, in Brunswick County, began planning to expand their sewer systems last year. The town hopes to locate the scalping unit near a local sports field or golf course that could be irrigated with reclaimed water. Spray Irrigation or Surface Discharge Systems These systems treat human waste by putting it into a large holding tank where bacteria digest the solids. The resulting liquid is then treated and sprayed on a nearby field that absorbs excess nutrients. Developers advocate these systems for new subdivisions in rural areas of Wake County. Nearby residents and environmental activists oppose the systems, however, fearing that discharge containing raw sewage could contaminate groundwater if the systems malfunction or aren’t properly maintained. In a report released last January, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency reported that of more than 140,000 surface discharge systems operating in the state, between 30 and 60 percent of the systems are either failing or have failed. 9