doc - Center for Environmental Farming Systems

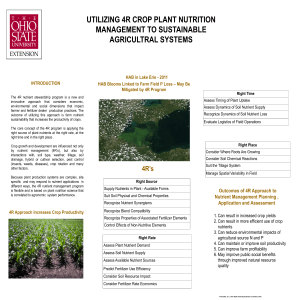

advertisement