famstc2 - mail.nvnet.org

advertisement

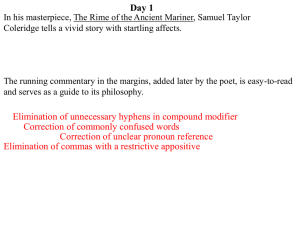

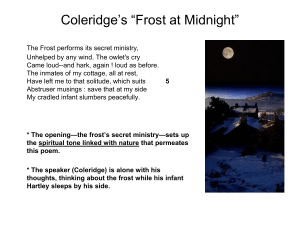

“Frost at Midnight:” Romanticism Exemplified A desert brings to mind heat and dryness. A tropical jungle, humidity and exoticism. A frostbitten steppe, wind and isolation. The act of associating different locations with their emotional and physical connotations is a common human trait. This association is seen in Romantic philosophy: cities are dark, destructive, vile, and noisome while nature is bright, regenerative, beautiful, and peaceful. The Romantics aggrandized the blessings of innocence, of peace, and of nature. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, an English Romantic poet, is famous for his dreamy and intellectually stimulating poems that exemplify Romantic thought. In Coleridge’s poem “Frost at Midnight”, the theme of the benevolence of nature and its effect on innocence is typically Romantic, just as the author’s use of poetic techniques such as the metaphor of the film of soot, the imagery of silence and of night, and a prevalence of spontaneity and meditation are. The reverence for nature’s benevolence towards innocence and childhood, as well as its formative power, is a prevalent theme within Romantic poetry and is found in copious amounts in “Frost at Midnight.” An example of such a reverence is when Coleridge laments that he grew up in a “great city, pent ‘mid cloisters dim” (l. 52) where he was trapped inside amidst the dirt and soot of Industrial England. Coleridge despised this “entrapment” and therefore he expresses in the poem his wish that the innocence and personality of his child be shaped by nature and its beauty, not by the city and its hideousness. Instead of being imprisoned by the city and its vices, Coleridge declares that his son “Shal[l] wander like a breeze/By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags/Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds…” (l. 54). The author believes that nature (i.e. God) is a far better formative power and teacher than the formal education provided within a cramped city. God is the “great universal teacher” that will far better “mould [his son’s] spirit” (l. 63-4) than the drab confines of a school. As well as being benevolent and formative towards both innocence and mankind in general, “Frost at Midnight” also expressed the Romantic belief that nature is the ideal location for a human and that the dark cities are evil and destructive. Coleridge espouses this concept by his desire to see his son raised not in the recesses of ugly cities, but within the beautifully developmental atmosphere of nature. The author’s own experiences within the city create a stark contrast within the poem. Nature, according to Coleridge, ensures that “all seasons shall be sweet to [my son]” (l. 65) in contrast to his experience within the city where he “saw nought lovely but the sky and stars” (l. 53). Coleridge connects and interlinks common poetic techniques used by Romantic poets in “Frost at Midnight,” such as the metaphor of the film and the prevalence of spontaneity and meditation. The film, a piece of soot fluttering on the grate of the fireplace, is a direct metaphor of Coleridge’s imagination at the time of composition of the poem. The film is described as being a “companionable form” whose “puny flaps and freaks” Coleridge relates to because his imagination is also undergoing rapid changes and movements (l. 19-20). Therefore, the “sole unquiet [film]” is exactly like his imagination: it is contorting and shifting in “this hush of nature” (l. 16-7). Coleridge’s imagination is a constant ebb and flow of thoughts and contemplations, thus lending to the spontaneity of the poem. The repetition of the line “Sea, hill, and wood” indicates a sense of spontaneity; daydreaming and thinking often lead to repetition of thoughts within the mind. Also, Coleridge’s random tangents upon different, seemingly unrelated subjects, as well as his outbursts of feeling or emotion (“But O!”), give the poem a spontaneous and stream-of-consciousness feeling (l. 24). This spontaneity makes “Frost at Midnight” appear to be a simple compilation of random meditations and contemplations by Coleridge, but in fact all the “random” meditations are intricately connected to contribute to an overall theme. For example, Coleridge meditates upon the loneliness and silence in the first section of the poem, upon his childhood education in the second, and upon the weaning of his child in the third. These three different meditations all connect to the overall theme of beauty, benevolence, and formative character of nature. The meditations also all have an underlying vein that relates to Romantic ideals: nature and to a lesser extent, individual freedom. Just as each individual meditation is connected, so are all three of the techniques mentioned above. Coleridge’s fluttering imagination, represented by the film, directly causes the continuous stream of conscious thoughts that create a meditative state of mind, therefore causing a feeling of spontaneity. Imagery within this poem is used to create an emotional atmosphere by constantly making references to the omnipresent silence, which is caused by the nightly aura. The persistent mentioning of the silence within the author’s abode is so prevalent that it creates a type of “noise” within the reader’s consciousness. Continuous references to the silence with words such as “calm,” “extreme silentness,” “inaudible,” “hush,” “silent,” and “quiet(ly),” buffet the reader, causing a throbbing within the consciousness. Not only is the silence so profound, it also “…disturbs/And vexes meditation with its strange/And extreme silentness” (l. 9-10). The reader sees, however, that the end of the poem largely reverses Coleridge’s vexation concerning the “extreme silentness”. At first the silence distresses and disturbs Coleridge, but gradually the author deviates to other topics of meditation until the end, where he seems to accept the silence as a good thing. The silence goes from “vex[ing] the meditation” of Coleridge to it being a benevolent and soothing presence: “silent icicles/Quietly shining to the quiet Moon” (l. 73-4). The nightly setting creates the silence throughout the poem. The night is a completely different emotional plane than that of day, where noises are prevalent and common. During the night, however, the slightest disturbances seem discordant and out of place. Just as silence is created by the night, so is a deep emotional connection created between Coleridge and the setting. Small, unnoticed paraphernalia, such as the film, the breathing of the child, and the sound of an owl are stark and noticeable during the night, where they would otherwise be ignored during the day. Also, the daydreaming caused by the loneliness and silence of the nightly vigil awakens within the author emotions and memories that would have remained dormant had he not remained awake during the late hours of the night. In Coleridge’s poem “Frost at Midnight,” Romantic philosophies are embodied through the theme of the magnanimity and regenerative power of nature, as well as his techniques for achieving the desired theme and emotional atmosphere are typically Romantic. If this poem were to be compared to a Neo-Classical poem, the major difference would be that there is far more stress on emotion rather than empirical postulation. The emotional and spiritual fluctuation is something uniquely Romantic, which is what attracts many to it. Coleridge’s adeptness at capturing the essence of Romanticism’s creative and emotional philosophy makes “Frost at Midnight” an ideal Romantic poem.

![Special Author: Coleridge [DOCX 17.00KB]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006968656_1-dea8d59f2ad6dce7da91a635543a7277-300x300.png)