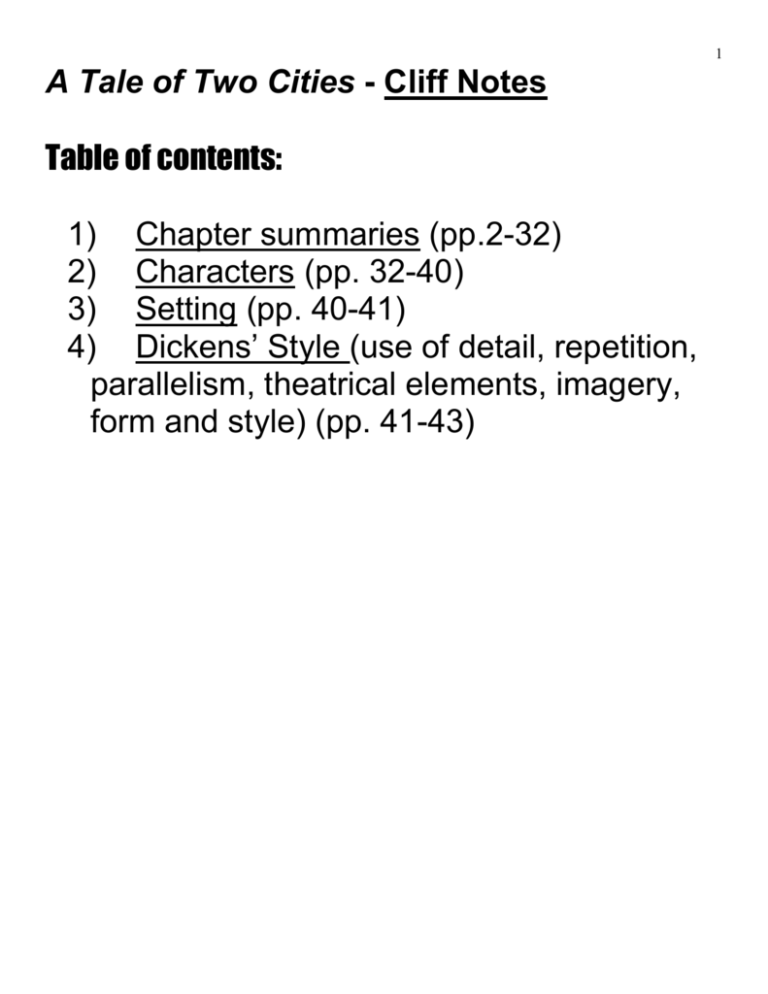

A Tale of Two Cities

advertisement