Tourism Policies and Urban Development in a Distressed City:

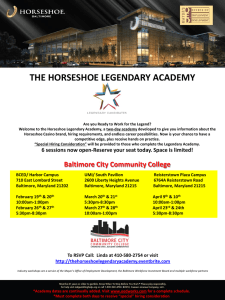

advertisement