Application

advertisement

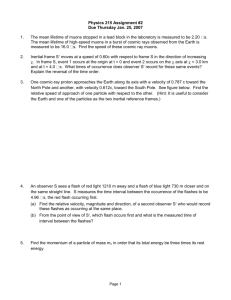

10 Applications II Classical Domain We now address some elaborations for realistic applications in higher dimensions and having independent dynamic parts. The technical details introduced here are widely used in statistical mechanics. They are illustrated with classical models of ideal gases and solids. Partition Function Revisited You saw that the partition function is a useful quantity for generating average energies, standard deviations, and Helmholtz free energy F. In fact, all the thermodynamic functions of the last chapter can, in principle, be constructed from Z. For discrete energy levels Ej, we wrote Z exp E j . j Often, the same energy level can be attained in multiple ways; for example, a hydrogen atom may have the same energy for 2 1values of angular momentum . We can group such degenerate terms together so that Z appears as Z j exp E j , (1) j where jrepresents the degeneracy of the jth energy level and the sum is now over differing energies. Canonical probabilities are then written wi j exp Ei Z . (2) A bridge to thermodynamics can be made through the simple connection with the Helmholtz free energy F, (3) F = - kT ln Z . Other thermodynamic potentials can then be constructed from relations like G F PV and F E TS . Independent Systems and Dimensions When two independent systems have corresponding entropies S1and S2, the combination of these systems should have a total entropy S given by S = S1 + S2. We say that entropy and information are “additive.” It is easy to show that an expression for the combined system is S k E1 E2 k ln Z1Z2 . The additivity of energy is expected, but the partition function for the composite is seen to be the product of the independent Z’s. The rule can be extended to any number of independent systems. The composite Z for N independent systems is Z Z1 Z2 Z N (4) Applications II 2 The same product rule for Z applies when you consider independent motions or independent dimensions. For example, a molecule that has independent modes of rotation, vibration and translation may be expressed in obvious notation as Z Z rotation Z vibration Z translation Similarly, if the dynamics can be easily separated into independent motions along axes x, y, and z, we can write Z Z x Z y Zz 1. Show that for independent systems 1 and 2, the entropy of the composite is given by S k E1 E2 k ln Z1Z2 . 2. Given that the partition function for an ideal gas of N classical particles moving in the x-direction in a rectangular box of sides Lx, Ly, and Lz is N 2m 2 L Z x x h (a) Write the partition function for the gas in three dimensions. (b) Calculate the pressure of the gas in terms of T and V (V Lx Ly Lz ) . 1 [ans. P NkT / V ] Hint: Calculate F and use F V P . Independent Particles We often must treat independent particles. If Z1 is the partition function for a single distinguishable particle, then the partition function for N such particles is simply (5) Z Z1N A further adjustment must be made for identical particles. At the molecular level particles of the same species are indistinguishable from each other. When there are N particles, they can be rearranged in N! ways each of which is indistinguishable from the others. (Thus the particles a, b, c can be arranged six ways; (abc), (bac),...etc.) The remedy for indistinguishable particles is to divide out the excess factor of N! from Eq(5): ZN (6) Z 1 N! 3. The partition function for a point particle moving in the x-direction in a rectangular box of sides Lx, Ly, and Lz is 1 2 m 2 Lx Z1, x h (a) Write the partition function for N of these indistinguishable particles. (b) Find the partition function for the particle gas in three dimensions. Compare your result with part (a) of problem 2. Applications II 3 Density of States Many systems have continuous energy levels and it is desirable or necessary to treat the partition function as an integral, Z exp E j exp E d , j where the density of states d is the number of states in a neighborhood around energy E. A single p cell in one-dimensional phase space is limited by the uncertainty relation, x px h . The number of states available to the system is the h h h number of accessible cells, h h dxdpx d . h Similarly, in three dimensions each particle contributes the factor dxdydz dpx dp y dpz (7) d h3 Note that the density of states is the continuum counterpart of the degeneracy factor in the discrete case of Eq.(1). Very often it is convenient to convert three-dimensionsonal integrals to spherical coodinates. In these cases we can write (8) dxdydz r 2 sin drdd Momentum integrals can be treated in pz the same way. In this case x, y, and z are replaced by px, py, and pz. The length of the position vector, p r x 2 y 2 z 2 , is then replaced by the momentum magnitude p px2 p2y pz2 py and we have px dpx dp y dpz p2 sin dpdd , where the angles now relate to the momentum vector p. 4. Use the diagram to confirm the volume element given in Eq.(9). (9) x Applications II 4 Application: Ideal Gas An application to ideal gas illustrates a typical calculation in statistical mechanics. This time we approach it with a more rigorous treatment based on the canonical distribution and the partition function. First the partition function is evaluated and then various relations between variables are generated using expressions derived in the last chapter. A select few such relations are collected here: F kT ln Z E ln Z F F P and S V T T V For your convenience, we also include two important definite integrals, 2 exp r dr 2 0 1 (10) and 1 2 2 exp r r dr 4 (11) 3 2 0 The following problem includes derivations of the ideal gas state equations and uses various thermodynamic properties. Although it is a repetitious example, it requires techniques necessary for many applications. 5. (a) Evaluate the single-particle partition function for a point particle of mass m confined to volume V. Do this two ways; (i) integrate over a three-dimensional volume element in momentum space as in Eq.(9), and (ii) treat the gas as if it is confined to a rectangular box and integrate over one dimension at a time. These calculations are shown on the following page. Be sure you can perform these (given the integrals above). (b) Construct the full partition function for a gas of N identical particles described in part (a). (c) Derive the average energy expression of the gas and show that its heat capacity. is given by CV 23 nR where n is the number of moles and R is the gas constant. (d) Write the Helmholtz free energy function and derive the ideal gas equation. (e) Find an entropy expression for the gas. Show that an adiabatic process obeys 2 TV 3 constant. Applications II 5 Solution to problem 5 (a) Single-Particle Partition Function by 3-D Integration (take h = 1 for convenience) Single-Particle Partition Function by 1-D Integration (take h = 1 for convenience) Notice the difference in integration limits. In one dimension momentum takes negative and positive values. In three dimensions p represents the magnitude p px2 p2y pz2 and can only take positive values. Applications II 6 Application: Classical Model of a Solid A simple classical model treats a solid as a collection of springs all of which have a common angular frequency . The energy of an individual spring is H a 2 p 2 b2 x 2 with a 2 1 2 m and b 2 21m m2 Now the integral over x is not trivial. For a single oscillator, we have 1 Z exp H d 3 exp a 2 p 2 d 3 p exp b2 x 2 d 3 x . 0 h 0 4 (a) Evaluate the single-particle partition function for a harmonic oscillator with mass m and angular frequency .. Do this by integrating over a three-dimensional volume element in momentum space and over a three-dimensional volume element in configuration space (as indicated above). (b) Construct the full partition function for a collection of N distinguishable oscillators described in part (a). This is a classical model of a solid. (c) Derive the average energy expression of the solid and show that its heat capacity. is given by CV 3nR where n is the number of moles and R is the gas constant. This model is adequate at room temperatures and above. Better results will be found by using quantum mechanical oscillators to model solids. Application: Equipartition Theorem The last problem was a special case of the equipartition theorem. Energy expressions and heat capacities for number of substances can be quickly approximated for ‘high’ temperatures. Each px2 and qx2 term in the Hamiltonian (energy expression) contributes an average energy of 12 nRT . When the Hamiltonian for an independent particle has the form H a1 p12 a K pK2 b1q12 bM q 2M , (12) where qj is the generalized coordinate associated with momentum pj, then the energy for a system of N such particles is NK M n K M (13) E kT RT . 2 2 The degrees of freedom refers to the number of terms on the right hand side of Eq.(12), K+M. Thus the heat capacity is the product of 12 nR and the number of degrees of freedom. Applications II 7 As an example, consider a material consisting of N springs with frequency . The Hamiltonian for one particle is H 21m p2 21 m 2r 2 so there are six degrees of freedom and the heat capacity is 3nR. This was the result in problem 6. A rigid diatomic molecule may translate and rotate around its center of mass. Translation contributes three degrees of freedom. Rotation contributes only two degrees of freedom corresponding to the angular momenta associated with each of two angles. Consequently, the heat capacity of a rigid diatomic ideal gas is 25 Nk . At high temperatures a vibration mode may be excited in diatomic molecule. This vibration simulates a one-dimensional harmonic oscillator contributing two more degrees of freedom (one from p2 and one from x2 terms) to produce a heat capacity of 72 Nk . 7 The energy of a rigid rotating molecule has the form H ap2 bp2 cp2 where the p’s represent momenta and a, b, and c are constants. Use the equipartition theorem to write the heat capacity of a gas of such molecules. [ans. 25 nR ]