Structural family therapy - Minuchin Center for the Family

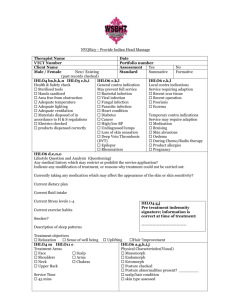

advertisement