9 Multi phase flow

advertisement

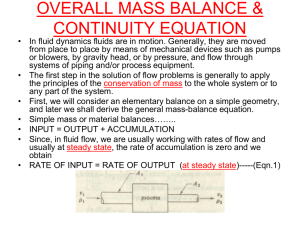

9 Multi phase flow Most wells produce more than one phase. Oil and gas usually flow together, and often also with water and solid particles. Figure 9.1 illustrates the typical flow patterns. Simplified sets are 3 main patterns of vertical flow: - Continuous fluid, with gas bubbles / fast particles - Continuous gas, with drops of liquid / solid particles and liquid film along the walls - Discontinuous flow: liquid plugs, broken up by large gas accumulations In horizontal flow, flow patterns will be similar, but with a tendency to stratification because of density difference. At the relative low velocity, gas and oil may flow in separate, stratified layers Figure 9.1 Typical flow patterns of liquid and gas 9.1 Rising and sinking of particles/drops/bubbles in static fluid Particles, droplets, or bubbles in a continuous fluid will rise or sink. This provides a basis for multi-phase flow calculations. 9.1.1 Sinking velocity for solid particles When a particle sink with a constant velocity, the gravity force acting upon the particle has to be as large as the friction force. That gives the flow balance outlined below Figure 9.2 Solid particle that falls in continuous gas or liquid For a spherical particle, the volume and cross-sectional area relate to particle diameter: Vs = d3/6, and As =d2/4 . By putting Fg = Ff, we can express sinking speed 0.5 4 gd s vs 3 f s 0.5 :density of the fluid s : Density of particle d : Diameter of the particle fs : Friction factor between the particle and the surrounding fluid (9-1) Friction factor depends on the Reynolds number of the border layer between the particle and fluid vs d (9-2) Re s : viscosity of the fluid surrounding Figure 9.3 shows the correlation between friction factor and Reynolds number, Lydersen /1976 /. Correlation for spherical particles can also be expressed analytically Reynolds Number Friction Factor Flow Ratio 500 < Res < 2.105 2 < Res < 500 10-5 < Res < 2 fs = 0.44 Turbulent boundary layer fs = 18.5 Res-0.6 Transition fs = 24 Res-1 Laminar boundary layer Figure 9.3 Friction Factor for solid particles in static fluid If sinking velocity of sand particles is greater than the flow velocity in a vertical well, then sand will fall down and gradually fill up well. In an inclined well the falling velocity will drag particles against the lower portion of the pipe cross-section. Turbulence will help to keep the particles in dispersion. Transportation of particles further depends on whether sedimentation or dispersion dominate. 9.1.2 Sinking velocity of small drops In a swarm of falling drops, the drops will continuously coalesce and break up. Turbulent forces tend to break up, while surface tension keeps drops together. This will be a continuous process, as indicated in Figure 9.4. Consider a drop with circumference: Sd , the surface tension will provide a force: F = Sd. The turbulent forces can be represented by the friction force: F f 1 2 f d vd2 Ad It seems reasonable to relate the maximum drop size to the ratio of these forces. This provides the critical Weber number. For a round drop, this can be expressed as 2 vd* d We F max Ff * (9-3) : Surface tension (N / m) vd* : sinking velocity of the largest drops Experiments indicate largest achievable (critical) Weber number in the range of 20-30. By setting (9-3) in relation with sinking velocity (9-1), we can express maximum sinking velocity as vd* 0.25 g l g Kd g2 (9-4) 4 We* Kd : dimensionless parameter group: K d 3 fd 0.25 Kd is dimensionless and can be considered as constant. For droplets that drop in static gas, this has been experimentally determined as Kd = 2.75 - 3.1. Figure 9.4 Drop size in continuous gas The majority of gas wells also produce some liquid, water and / or condensate. Velocity of small droplets are often used as a criterion for flow velocity to prevent fluid collection in the well, Turner & al / 1969 /. The idea is that if liquid largely exist by itself as a film along the well wall, it will still mainly be transported as droplets. If the gas velocity is greater than sinking velocity for the largest liquid drops, the liquid droplets will be transported out of the production pipe. 9.1.3 Rise velocity for small bubbles Small bubbles that rise in the continuous liquid are subjected to similar forces as liquid droplets in the gas. Stability consideration and the formula for maximum velocity for the rising gas bubbles are similar vb* 0.25 g l g Kb l2 (9-5) Flow conditions around a gas bubble that rises in viscous liquid will be different from a liquid drop that falls in small viscous gas, so the friction factor will be different. For gas bubbles the rise in the stagnant liquid is found by Harmathy / 1960 /: Kb = 1.53. 9.1.4 Rising velocity for big bubbles If bubbles are so large that they fill the entire cross-section of the pipe, (figure 9.5), they will be stabilized by the pipe wall. Rise of large air bubbles in the water is primarily governed by liquid flow around the bubble front. After passing the bubble front, the liquid will flow along the pipe wall as a free-falling film, which has no influence on the rise velocity. Rise velocity has been derived theoretically by Dumitrescu / 1943, (9-6). Dimension Analysis and measurements of Davis & Taylor / 1950 / gave nearly identical results. Figure 9.5 Large bubble in the pipe (“Dumitescu bubble " / "Taylor bubble") g vD 0.347 g D 1 l vD: rise velocity of large bubbles in the vertical pipe D : inner diameter of pipe (9-6) The sinking liquid film will mix with gas bubbles in boom, as illustrated above. By comparing (9-5) and (9-6), we find that small air bubbles rise faster than the large ones if pipe diameters are less than 50 mm. This means that the small bubbles in the small pipe will have the tendency to collide and coalesce with large bubbles. While in large pipes, small bubbles that separate from the end of a larger one will trail behind. Based on this, it has been argued that Dumistrecsu bubbles are not stable when the pipe diameter is greater than 50 millimeters. Zukoski / 1966 / explored the rising velocity of the large bubbles for different surface tensions, viscosity and pipe inclinations. Surface tension appeared to have some effect on small pipe diameters. The effect of viscosity attributed to the Reynolds Number defined by fluid density, liquid viscosity and the rising viscosity of the bubble: Re = vD D/. Viscosity had little significance for Reynolds Number above 20. Zukoski found that the bubble velosity reach a maximum at pipe slope around 35o compare to the horizon (inclination 55o) Rise velocity for large oil accumulations in inclined pipe filled with water has been experimentally found to be in reasonable compliance with Zukoski’s results. In the vertical well, oil was found to disperse. 9.1.5 Bubbles and droplets of flowing fluid Turbulence forces due to flow will also break up drops and bubbles. Hinze / 1955 / considered the relationship between the turbulent forces and surface forces as a Weber Number. u 2d We (9-7) Break up forces are due turbulent velocity fluctuation: u 2 This can be relatioed to energy dissipation u 2 d 3 2 (9-8) Energy dissipation may have different causes: the flow through nozzle, mechanical stirring, wall friction, pumping. For flow in the pipe energy dissipation per mass unit relates to friction loss v dp 1 1 3 f v dx 2 D (9-9) By putting (9-8), (9-9) into the relationship between the turbulent forces and surface forces into the Weber number (9-7), we can associate the maximum droplet size to the fluid in flow conditions 1 d C 2 5 * 3 5 (9-10) The dimensionless constant relates to the critical Weber number of (9-7): C We* 3 5 . Experimentally the constant has been determined as C =0.725. Figure 9.6 below shows the maximum bubble size predictions, using the methods above, for the parameters :g = 200 kg/m3, l = 900 kg/m3, f =0.02, = 40 .10-3 N/m, D = 0.1 m. Figure 9.6 Bubble Size Estimates The figure shows that when the velocity is less than 0.2 m / s, the bubble size in the flowing liquid larger than the size of the bubble in the stagnant fluid. Thus, it may be expected that the size is controlled by turbulence in the boundary layer due the bubble rise. So a maximum bubble size of about 27 millimeter may be expected. At higher velocity, the turbulence generated by the overall flow will control the bubble size. So the maximum bubble size will decrease with rising flow velocity. (To estimate the drop size more realistically, we should to "add" turbulence contributions from buoyancy and flow.) The relations above may also be useful for separator design. Well and valves ahead of the separator should be arranged and dimensioned so that high turbulence and fine dispersion are avoided . 9.2 Fluid 9.2.1 Mass flow and superficial velocity Consider a pipe segment in a well where oil and gas flows: Fig 9.7. Figure 9.7 Steady-state multi-phase flow Under stationary (steady-state) conditions, the mass flow is constant through any cross section along the pipe. Knowing production rates at standard conditions: qg, qo, qw, we can express volume streams down in the well by using the black oil model. It is convenient to represent the volume streams by superficial velocities: flow rate/ pipe cross-section vsg vsl Qg A qo Rt Rs Bg d 2 / 4 Ql qo Bo qw Bw A d 2 / 4 (9-11) (9-12) vm Ql Qg A vsg vsl (9-13) 9.2.2 Fluid velocity, volume fractions and two-phase flow Flow velocity in the pipe, defined as the flow rate divided by cross-sectional area. Then flow velocities can be linked to superficial velocity and fraction vg Qg vl Ql Ql A vsl Al Al A yl Ag Qg A Ag A vsg yg (9-14) (9-15) yg : gas fraction yl : liquid fraction Average density of fluid mixture in a pipe segment can be linked to fluid densities and fractions TP g Ag l Al A g y g l yl (9-16) Gas and liquid fractions can be measured indirectly, e.g.: by measuring the electrical impedance for the mixture flowing. Since the bubble and the gas usually have different impedance, such measurements indicate fractions of gas and liquid. Since the ability to absorb the gamma rays is also different for liquid and gas, gamma absorption can also be used for measuring in situ fractions. A more direct method is to close a pipe segment and measure the volumes of liquid and gas. Liquid fraction is equivalent to the fluid volume, divided by the volume of the pipe segment. 9.2.3 Flux fractions and flow density Flux fractions set flow rate for each fluid in relation to the total flow volume. Flux fractions can be linked to superficial velocity Qg g l Qg Ql vsg (9-17) vm Ql v sl Qg Ql vm (9-18) Average density can be attributed to the flux fractions g Qg l Ql m Qg Ql g g l l (9-19) From the definitions (9-17), (9-18) follows that when fluid velocity approaches the velocity of gas, the volume fractions, for example, liquid, approach flux fraction yl Al Ql v Ag Al Q l Q g l vg l (9-20) vl v g 9.2.4 Slip Gas has less density and viscosity than the liquid and will usually flow faster. Zuber & Findlay /1965 / proposed to link gas velocity to total superficial velocity v g Co vm vd (9-21) Co: distribution parameter for bubbles in flow, usually: 1.0 <Co <1.2 vo : Buoyancy velocity of the gas bubbles, or sink velocity for droplets By combining (9-13) and (9-14), we can express the liquid fraction directly yl 1 vsg Co vsg vsl vd (9-22) Z & F model has been widely used, but is misleading in many cases. Asheim /1986 / relates gas velocity directly to the velocity surrounding liquids v g Co vl vo (9-23) By combining the relationship between velocity and superficial velocity to the drop relationship (9-23), the liquid fraction is expressed as 1 yl 2 2 vsg v v Co sl 1 4Co sl vo vo vo v 1 vsg Co sl 1 2 vo vo (9-24) Relationship (9-24) is more complicated than (9-22), but avoids most shortcomings of the Z & F model. If the gas flows up and the liquid down, equation (9-24) gives one, two, or no solutions. One solution predicts stable counter current flow. No solutions imply that counter-flow at the given rates is impossible. Two solutions imply transition between continuous liquid and continuous gas. One of these solutions will then usually be unstable, such that the flow regimes will change 9.3 Pressure and flow capacity 9.3.1 Flow equations for gas and liquid To start, we may assume that the phase flows in stratified channels, as outlined in Figure 9.8 below. The gas flow equation becomes Ag dp Ag g g x dx Ag g vg dvg gw S gw dx i Si dx 0 Ag: gas-filled cross-sectional area Sgw: contact length (perimeter), gas against pipe wall gw: shear stress, between gas and pipe wall Si: contact length between gas and liquid i: shear stress, between gas and liquid The flow equation for the liquid channel becomes (9-25) Al dp Al l g x dx Al l vl dvl lw Slw dx i Si dx 0 (9-26) Figure 9.8 Gas and liquid flow with different rates In the equations (9-25), (9-26) above, friction resistances are estimated by shear stresses: force / contact-area. Shear stress can be correlated against speed and density: 1 2 f F v 2 , usually by Fanning’s friction factor: fF. For calculation of pressure drop in pipes, the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor is more commonly used. This is by definition 4 times greater than Fanning’s: f = 4fF. Otherwise, they are equivalent, can be estimated by the same correlations, and pressure loss can also be calculated based on shear stress. For horisontal pipes, flow with small velocity will be stratified. Taitel & Dukler /1976 / predicted velocity and fractions of stratified flow and used as stability analysis to assess whether the stratified solutions were physically realistic, or whether the gas and liquid would be divided in any way in the pipe. 9.3.2Mixed-flow If gas and liquid flow together, we need a flow equation for mixture. We find it by putting: Ag/A = yg , Al/A = yl into (9-25) and (9-26), and adding them. This eliminates the interphasial shear. The mixed flow equation becomes dp g y g l yl g x dx g vg y g dvg l vl yl dvl g S gw lw Slw A dx 0 (9-27) The last part in (9-27) contains shear stresses and wetted perimeters. If we presume that perimeter is proportional with fractions (Sgw=ygS=ygd), and represent the velocity by (9-11), (9-12), we can develop shear contribution as g S gw l Slw A 1 f v vsg d 1 f v vsl d 1 f v vsg f v vsl g g sg l l sl g g sg l l sl 2d d 2 / 4 8 yg 8 yl yg yl 1 When gas and liquid flow in the same direction, we can ignore the absolute values. It is useful to relate shear to rate and flux density (9-17), (9-18). If we also assume equal friction factors for liquid and gas : fg = fl =fo, we get g S gw l Slw A 2 l2 2 1 o 1 g f vm g l 2 d yg yl (9-28) Often the shear contribution (9-28) expressed as for flow of homogeneous mixture g S gw l Slw A 1 1 fTP m vm2 2 d (9-29) Here fTP is thetwo phase friction factor, estimated from the correlation for single-phase flow, with a correction factor for the drop: fTP f ocTP (9-30) The comparable single phase friction factor fo is estimated by standard single-phase correlation (for example : fo=0.16/Rem0.172) with Reynolds Number for the homogeneous mixture, usually defined as Re m m vm d g g l l (9-31) From (9-28), (9-29) follows the slip correction factor then becomes g 2g l l2 g yl 1 l 2 l y g l 2 cTP m y g m yl m yl 1 yl With this theoreteical basis, we can express and calculate the pressure gradient (9-32) dvg 2 dv 1 dp TP g x g vsg l vsl l fTP m vm 0 dx dx dx 2 d (9-33) The theory above involved many assumptions and approaches. Published models for steadystate two phase flow may deviations somewhat from the basis outlined above. 9.3.2 Pressure and flow conditions along the pipe Relations above are apply to steady-state flow at a given pressure, temperature and flow rate. Along the well pipe we will then have constant mass flow, while pressure and temperature will change. Equation (9-33) enables calulation of pressure changes along the pipe, and thus also phase relationships, viscosity, volume and velocity. A common task is that we know the expected well pressure: pw, for given reservoir pressure and rate, and need to estimate the tubing head pressure: pth. We can formally approach this as pth pw dp T Lw dx p (9-34) where: Lw dp dx : length along well pipe T : Average pressure gradient, estimated from (9-31), p Well pressure: p pw pth T Tth , And temperature: T w 2 2 Since we do not know the average pressure in the well before we have estimate the pressure, iterations are required: we may estimate the pressure gradient at the bottom, solve (9-34), and then use the solutions to estimate the average pressure. In many cases it provides pretty good estimate of pressure. Such step will be called a single-step Runge-Kutta solution. If the pressure gradient change much, it would be desirable to assume the pressure and flow conditions at intervals along the pipe. The algorithm can then formally be expressed as pi 1 pi dp dx Ti 0.5 Li 1 Li (9-35) pi 0.5 Figure 9.9 shows the estimated pressure profiles. The parameters for calculation are: pR = 310 bar, J = 20 Sm3/d/bar, Rt = 200, d = 0.1 m, o = 0.9, g = 0.58, Co = 1.1, vo =0.1 m for parameters: pR = 310 bar, J = 20 Sm3/d/bar, qo = 200 Sm3/d, Rt = 200, d = 0.1 m, o = 0.9, g = 0.58, Co = 1.1, vo =0.1 m . At low pressure, pressure gradient will decline significant. This is because the gas is released and is expanding, so that the average density of the fluid mixture is declining. We observe that the pressure at production rate 200 Sm3/d is larger than at smaller rates . Figure 9.9 Pressure, estimated with the flow model outlined above Figure 9.10 below shows how the liquid fraction changes along the pipe, from 0.9 at the bottom, to 0.1 near the top ,with the production 200 Sm3/ d. Figure 9.10 The estimated liquid fraction along the production pipe Figure 9.11 shows the superficial velocity along the pipe. Figure 9.11 Superficial velocity (flux volume) along the pipe Superficial velocity for liquid decreases with increasing pipe diameter, because disolved gas evaporates. Actual velocity of gas and liquid can be estimated by (9-14) and (9-15). The actual flow velocity of gas will be slightly over the sum of superficial velocity; for liquid, a little bit smaller 9.4 Optimal flow conditions For single phase flow, larger pipe diameter always means less flow resistance. When several phases flow, there usually exists an optimal diameter that provides favorable flow conditions: least pressure gradient, proper sand transport, small corrosion due to flow. The assessments below includes not really optimization, but addresses the effect of different measures and flow conditions on pressure loss. It assumes constant diameter pipe along well. (Large diameter in the upper part of the well is often favorable.) 9.4.1 Impact of production rate Figure 9.12 shows measured pressure differences, between the bottom and top of the well 40 on the Ekofisk field. The data is previously provided as attachments to exercise 6 (Observation and the plot is made by Zenit Federico, a student in 2000.) We see that pressure loss smallest when the production is 600-700 Sm3 / d. Figure 9.12 Measured pressure in the production pipe at different rates; Ekofisk well 40 At low flow velocity, liquid accumulates in the production pipe. In such case average density approaches liquid's density, while wall friction approaches zero. At high flow increases, the average density of the mixture approaches the average for flow, while the friction loss increases with the square of the velocity. Between these two limits, the pressure losses has a minimum value. Figure 9.13 shows the pressure for different rates, based on the data set previously applied for Figure 9.9. We observe that the highest tubing head pressure is estiamted at the production rate of about 180 Sm3 / d. Figure 9.13 Wellhead pressure characteristics of the well which produces oil and gas The figure above shows that for the 10 bar pressure, rate can be both 50 Sm3/d and 400 Sm3/d. Probably the well head rate will be stable only at the separator pressure of 10 bar. It will be difficult to start well, with separator pressure 10 bar 9.4.2 Effect of pipe diameter Larger pipe diameter means less flow velocity. For one phase flow, this will always reduce the flow resistance and provide less pressure drop. For multi-phase flow, the low velocity means that the gas bubbles rise through the liquid, so that the average density approaches the density of the liquid. Therefore, in multi-phase flow, large diameter may imply higher pressure gradient. Figure 9.14 shows the pressure characteristics for different rates and diameters. Figure 9.14 The effect of pipe diameter In gas wells, it is quite common to have larger pipe diameter in the upper part of the well, where the velocity will be the highest. Old gas wells may sometimes be refurbished with smaller diameter (velocity string) to prevent the accumulation of fluid. 9.4.3 Impact of the pressure When the pressure drops, the gas releases and expands. Falling pressure will provide greater fraction of gas, lighter fluid mixture and greater velocity. Reduced pressure will reduce the static pressure loss contribution. However, the reduced pressure also means greater flow rate and greater velocity, which will increase the wall friction contribution. We may therefore expect an optimum pressure (providing least pressure gradient), for a given rate and diameter 9.4.4 Impact of gas / oil ratio (GOR) All reservoir fluids have their natural gas / oil ratio. Sometimes we inject gas into the production pipe, to reduce the average density of the mixture, doing that we usually increase GOR. Figure 9.15 illustrates the tubing head pressure characteristics as a function of gas / oil ratio. Figure 9.15 Well head pressure as a function of gas / oil ratio The figure shows that under given conditions, the pressure will reach a maximum gas / oil ratio: 2500 Sm3/Sm3. With oil production: 200 Sm3 / d and natural gas / oil ratio: 200 Sm3/Sm3. Gas injection required will be (2500 - 200) * 200 = 4.5.105 Sm3 / d. 9.5 Flow regimes Flow slippage will depend on the flow conditions: In a flow with, for example, 5% gas and liquid, bubbles will rise. In a flow with 95% gas and 5% liquid, droplets will sink relative to the gas velocity. To estimate rising or sinking velocity, we need to know wheter gas or liquid is continuous. Figures 9.16 and 9.17 below illustrates flow regimes. A main classification principle is wheter liquid or gas flow is the larger. The relationship: vsg = vsl has been drawn into both figure 9.17 and 917,, and we see that both regime maps relate to this. Figure 9.16 Regime map for vertical gas/liquid flow, Duns & Ros / 1963/ Regime map shown in Figure 9.16 is based on measurements. Expressing the map in terms of dimensionless variables, surface tension and liquid density variations are in principle included Figure 9.17 Regime Map for vertical gas/liquid flow at atmospheric pressure Regime map shown in Figure 9.17 is based on simple criteria related to the liquid fraction, densities and velocity. The criteria are linked together by Kabir & Hasan / 1990 /. Regimes based models should provide better connection to flow mechanisms. However it is not always so that regime based models offer better prediction. Theses at this institute have shown that, for example, Kabir & Hasan model applied to the Ekofisk data, prediction of pressure drop less accurately than a homogenous flow model neglecting regime transitions. 9.5 References 1943 Dumitrescu, DT: "Strömung an einer Luftblase in senkrecthen Rohr" Z. angew. Math. Mech., 1943, vol. 23, no. 3, pp 139-149 1950 Davis, R.M., Taylor, G.I.: "The Mechanics of Large Bubbles Rising Trough Extended Liquids and Through Liquids in tubes " Proc. Royal Soc., London, vol. 200 series A, 1950, pp 375-390. 1955 Hinze, J.O.: "Fundamentals of the Hydro Dynamic Mechanisms of Splitting in Dispersion Processes ", AICHE J. (Vol 1, No. 3), 1995, pp 289-295 1960 Harmathy, T.Z.: "Velocity of Large Drops and Bubbles in Media Of Infinite or Restricted Extend " AICHE, no. 6, p. 281, 1960. 1962 Nicklin, DJ, Wilkes, JO, Davidson, JF: "Two Phase Flow in Vertical tubes" Trans. Instn. Chem. Engrs. Vol 40, 1962, pp 61-68. 1963 Duns, H., Jr. and Ros, N. C. J.: Vertical Flow of Gas and Liquid Mixtures in Wells, Proc. Sixth World Pet. Congress, Frankfurt (Jun. 19-26, 1963) Section II, Paper 22-PD6. 1965 Zuber, N. & Finlay, J.: "Average volumetric concentration in two-phase flow systems" Trans ASME, J. Heat Transfer. C87, 453-468 1966 Zukoski, EE: "Influence of viscosity, surface tension and inclination Wednesday angle motion of long bubbles in closed tubes " Journet. of Fluid Mechanics 1996, vol. 25, p. 4, pp 821-837. 1974 Ashford, FE: "An Evaluation of Critical Multi-Phase Flow Performance Through Well Head Chokers " JPT, Aug. 1974, p. 843. 1976 Taitel, Y., Dukla, A.E. : "A Model for predicting Flow Regime Transitions in Horizontal and Near Horizontal Gas-Liquid Flow " AICHE Journet., Vol 22, No. 1, Jan. 1976, pp 47-55. 1976 Campbell, JM: Gas Conditioning and Processing. (Vol 1) Campbell Petroleum Series, 121 Collier Drive, Norman, OK 1977 Kubi, J., Gardner, GC: "Drop sizes and Drop Dispersion in Straight Horizontal tubes and Helical Coil " Chem.Engr.Sci., Vol 32, 1977, pp 195-202. 1978 Karabelas, A.J. "Droplets Size Spectra Generated in turbulent Pipe Flow-Dilute of Liquid / Liquid Dispersions " AICHE Journal, Vol 24, No. 2, March 1978, p 170 1986 Asheim, H.: "MONA, An Accurate Two-Phase Well Flow Model Based on Phase Slip Page" SPE Production Engineering, May 1986, pp 221-230 1990 Kabir, C.S. and Hasan, A.R.: "Performance of two-phase gas / liquid flow model in vertical wells" J. of Petroleum Sci. and Engr, 4, 1990, 273 1991 Basniev, K.S. & Many others: "Thermal Dynamic model for the provision of the flow capacity of gas wells" (in Russian) Gasprom 1991