Eulerian Paths

advertisement

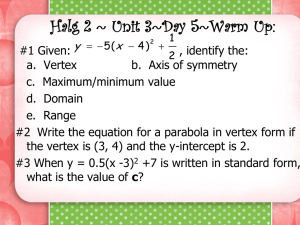

7.2 Eulerian Paths Definition 1. An Eulerian path is one that uses every edge in a graph exactly once. An Eulerian circuit is an Eulerian path that is a cycle, i.e. it ends at the same vertex that it starts at. Not every graph has an Eulerian path or circuit. There is a simple criterion for determining if a graph has an Eulerian path or circuit and in this section we discuss an algorithm to find a one if there is one. Example 1. A company has offices in the six cities that are the vertices in the graph at the right. These are connected by a computer network that has direct data links between some of the offices. These are represented by the edges in the graph below. Grand Rapids Chicago East Lansing Battle Creek Detroit Every five minutes the server in the home office of Detroit does a test of the network by sending out a test message that will go through every direct link. The message can Indianapolis specify the sequence of links in order that the message will travel. Is there a way it can traverse each link exactly once and start and end in Detroit? If so, what is a the sequence in edges in this route? This is an example of a situation in which one wants to find an Eulerian circuit in a graph. First, let's discuss the criterion for determining if a graph has an Eulerian circuit or path. B Consider a path that doesn't use any edge more than once. It might not use some edges, but it should not use an edge more than once. At the right is a typical path of this sort in some graph. Let's count the number of times, d, the path touches each vertex. We get the table of values at the right. A C H F G D Note that for each vertex except the start and finish the path touches the vertex an even number of times. This is because every time the graph arrives at the vertex it also leaves the vertex, which produces and even count. At the starting and finishing vertex it touches the vertex an odd number of times. This is because every time the graph arrives at the vertex it also leaves the vertex except for the start or finishing edge which has no companion edge. This produces an odd count. 7.2 - 1 E Vertex A B C D E F G H d 1 1 6 2 2 4 4 2 If the path were a cycle then it would touch every vertex an even number of times. There is some terminology related to this. Definition 2. The degree of a vertex in a graph is the number of edges touching it. The argument above proves the following Theorem. Theorem 1. If a graph has an Eulerian circuit then every vertex has even degree. If a graph has an Eulerian path that is not a circuit, then every vertex except two have even degree. The Eulerian path must start and end at the vertices with odd degree. If one looks at the graph in Example 1, then the vertices have the following degrees. So there is no Eulerian circuit. If there is an Eulerian path it would start and end in Detroit and Battle Creek. The following converse of Theorem says there is an Eulerian path or circuit if the condition in Theorem 1 is satisfied. Vertex Chicago Grand Rapids Battle Creek Indianapolis East Lansing Detroit Degree 2 4 5 4 4 3 Definition 3. A graph is connected if there is a path between every pair of vertices. Theorem 2. Suppose a graph is connected. If every vertex has even degree there is an Eulerian circuit. If every vertex except two has even degree there is an Eulerian path. Proof. First consider the case where every vertex has even degree. We pick any vertex, call it v, and start out from that vertex traversing edges making sure that we don't traverse any edge more than once. Continue on until we get stuck, i.e. reach a vertex where there are no more unused edges. This creates a certain path p. Claim. We must be stuck at the vertex v that you started at. The reason for this is that the path p uses up an even number of edges at every vertex except at the start and finish if they are different. So if the start and finish were different then an odd number of edges would be used up at the finish. Since every vertex has even degree we would not be stuck at the finish. So we must be stuck at the vertex v that we started at. In other words the path p is a circuit. If this path uses every edge we are done. If not we extend this initial path as follows. First note that the initial circuit touches every vertex an even number of times. This leaves an even number of unusded edges at every vertex. Pick an unused edge that touches some vertex w on the original circuit and start out from that vertex traversing unused edges making sure that we don't traverse any edge more than once. Continue on until we get stuck again, i.e. reach a vertex where there are no more unused edges. This 7.2 - 2 creates another path q. By the same arugment q must be a circuit, i.e. it must return to the vertex w that we started from. Now splice the second circuit q into the original circuit p by starting out at the starting vertex v of the original path p and going until we reach w. Then traverse the second circuit q until we come back to w. Then continue on the original circuit p until we come back to v. This creates a larger circuit that uses all the edges of both the original cirucit p and the second circuit q. We can continue in this fashion until we have used up all the edges and have created an Eulerian circuit. Now consider the case where every vertex except two have even degree. The proof of this case case is very similar to the first case. This time we start out at one of the vertices v with odd degree and traverse edges until we get stuck. An argument similar to the above shows we must be stuck at the other vertex of odd degree. If this doesn't use up all the edges, then the unused edges much touch every vertex an even number of times. At this point the argument is the same as the first case. // Grand Rapids Example 2. Consider the graph in Example 1. Let's find an Eulerian path the starts in Detroit and ends in Battle Creek. If we start out in Detroit and traverse edges until we get stuck, one possibility is (1) Battle Creek Chicago Detroit D – BC – EL – GR – BC – C – I – BC where D = Detroit, BC = Battle Creek, etc. This is pictured at the right. Indianapolis The unused edges are pictured at the right below the initial path. Note that the unused edges touch every vertex an even number of times. Now we can start out at East Lansing and traverse unused edges giving the circuit (2) East Lansing Grand Rapids Chicago EL – C - GR – I – D - EL We splice the circuit (2) into the path (1) by starting at Detrot, traversing the path (1) until we get to East Lansing, then following the circit (2) until we get back to Lansing and then following the remainder of the circuit (1). East Lansing Battle Creek Indianapolis This gives the following Eulerian path for the original graph in Example 1. 7.2 - 3 Detroit D – BC – EL – C - GR – I – D - EL – GR – BC – C – I – BC Grand Rapids East Lansing It is pictured at the right. Battle Creek Chicago Detroit Directed Graphs. In the above we have been assuming the graphs are undirected. The same problem of finding an Eulerian path or circuit is of interest in a directed graph Indianapolis where in the path or circuit we must traverse each edge in its given direction. Pretty much the same discussion goes through. However, now it is necessary to distinguish an edge going into a vertex from an edge going leaving a vertex. This leads to the following modified definition of the degree of a vertex. Definition 3. Consider a vertex v in a directed graph. In(v) = the incoming degree of v = the number of edges coming into v Out(v) = the outgoing degree of v = the number of edges going out of v With this definition we have the following analogue of Theorems 1 and 2. Theorem 3. Suppose a directed graph is connected. Then there is an Eulerian circuit if and only if In(v) = Out(v) for every vertex v. There is an Eulerian path if and only if the following is true. i. Out(s) = In(s) + 1 for some vertex s. ii. In(f) = Out(f) + 1 for some vertex f. i. Out(v) = In(v) for every vertex v other than s and f. The proof is similar to the proofs of Theorems 1 and 2. Example 3 (an Analogue to Digital Converter). One has a dial whose rim turns and whose center is stationary. The center 0 1 is conducting and the rim is divided up into eight segments, some of which are 1 0 conducting and some are not. Thus there are eight different positions for 1 0 1 1 the dial. 0 0 + There is a wire leading from a power supply to the center and there are wires - power supply 7.2 - 4 1 leading from three positions adjcent to three of the positions on the rim on the upper right. The center touches the rim and the wires on the upper right touch whatever three segments in the rim happen to be next to the wires. So one of three wires carries a high voltage (which represents a 1 bit) if it happens to be touching a conducting segment in the rim. Otherwise the wire is grounded (and represents a 0 bit). Thus for each dial position the three wires represent a three bit sequence. We would like to adjust the conducting segments on the rim so each dial position has a different corresponding three bit seqence in the wires. In the configuration above this is not true, since the three bit sequences corresponding to the eight positions on the dial are 101, 010, 001, 100, 110, 011, 101, 010 Here we start with dial in the current position and rotate the dial counter-clockwise. We read the three bits on the dial counter clockwise so we are reading what is displayed on the right. Note that 101 and 010 appear twice while 000 and 111 don't appear, so this assignment of conducting segments on the rim is not what we want. There is a solution to this problem involving Eulerian circuits. We make the following directed graph. There are four vertices corresponding to the four two bit sequences 00, 01, 10 and 11. There are eight edges labeled with the eight three bit sequences 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, 111 01 011 001 The edge xyz goes from the vertex xy to the vertex yz. The graph looks like this. 000 00 101 010 11 111 A path corresponds to a way of labeling the segments 100 110 on the rim. We start out with the three bits of the first 10 edge and then add on the left most bit of each successive edge. An Eulerian circuit corresponds to the desired way of labeling the segments on the rim. This graph meets the condition for an Eulerian circuit since each vertex has incoming and outgoing degree 2. It is not hard to construct an Eulerian circuit. One possibility is 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 000, 001, 010, 101, 011, 111, 110, 100 1 + - power supply where we have used the edge labels. The corresponding dial is at the right. 7.2 - 5 0 0 0 Hamiltonean Paths and Circuits. Definition 4. A Hamiltonean path is one that visits every vertex in a graph exactly once. A Hamiltonean circuit is a Hamiltonean path that is a cycle, i.e. it ends at the same vertex that it starts at. Not every graph has a Hamiltonean path or circuit. For example, the graph at the right doesn't have a Hamiltonean path since it would have to include each of the four edges in order that the path visit each of the vertices A, B, C and D. However, this would mean that it would visit E more than once. Unfortunately there is no simple criterion for determining if a graph has an Hamiltonean path or circuit. 7.2 - 6 B A E D C