the case of multiplicative structures

advertisement

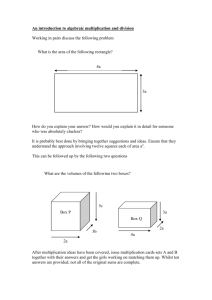

OBSTACLES IN APPLYING A MATHEMATICAL MODEL: THE CASE OF THE MULTIPLICATIVE STRUCTURE Irit Peled - University of Haifa Leonid Levenberg, Ibby Mekhmandarov, Ruth Meron Center for Educational Technology, Tel-Aviv Alex Ulitzin - Ministry of Education, Jerusalem Third and forth grade children, who started learning about multiplication in second grade, do not tend to use multiplication in multiplicative situations. This study looks at children’s choice of mathematical models in different non contextual displays: equal groups, rectangular arrays, and a rod model (which they use in class). The findings show that many children do not perceive the displays as representing multiplicative situations. Even children who exhibit knowledge of multiplication facts do not apply their knowledge in these tasks. Instead, they use addition and counting strategies. An important goal in teaching mathematical operations is the development of schemes, such as the additive scheme or the multiplicative scheme. These schemes, or structures can act as mathematical models of given situations. Usually the situation does not uniquely determine the structure, nor does it easily hint that a certain mathematical model can be used (although conventional school word problems might imply that it does). We teach children basic operations with the intention that they apply them in different situations. We also expect to see progress over time in the choice of a model, i.e. in the ability to apply more efficient models in the relevant cases. Given a rectangular array of objects with the task of finding their total number, it is expected that a young child will count the objects one by one. An older child will count the elements in each row and then add up the rows. An even older child is expected to realize the size equivalence of the rows, i.e. the repeated addition structure and then add or multiply, or recognize the rectangular array structure, and multiply the number of rows by the number of columns. The above description talks about different structures, which have been identified by several researchers. A lot of the research on multiplicative structures deals with the categorization of multiplicative situations (Vergnaud, 1983; Schwartz, 1988; Nesher, 1988) and with children’s word problem solving (Fischbein et al., 1985; Kouba, 1989; and many other significant works reviewed by Greer, 1992). 1 Some of theses researchers have focused on younger children’s work. Carpenter et al. (1993) show that even kindergarten children can solve some types of multiplicative word problems. Kouba (1989) looks at solution strategies of children in grades 1-3, and is interested more in the nature (and quality) of their solutions than in the question whether they can answer a given problem correctly. Kouba uses equivalent set problems (later termed repeated addition problems or mapping rule problems) and finds that children use a variety of counting strategies. She also observes that the intuitive model that children seem to have for equivalent set problems is linked to the intuitive model for addition as both involve building sets and then putting them together. Similarly, Mitchelmore and Mulligan (1996) show that during their second and third grades children use many different strategies in solving multiplicative problems. These strategies include quite a lot of addition and counting calculations. However, they also find that over time the strategies are chosen more efficiently. These different research findings suggest that children do not necessarily use multiplication in solving multiplicative word problems. Many children use addition and some choose to use a long counting process. It is often claimed that children are efficient and use a more effective tool or a shorter route once they possess it. Such a behavior is described by Woods, Resnick, and Groen (1975) in the case of choosing between solution strategies in subtraction (e.g. going two steps backwards in 9-2 while counting up from 7 to 9 in 9-7). This behavior is also evident in Siegler and Shrager strategy choice model (1984), where children choose to retrieve an addition fact rather than count, when they reach a reasonable degree of confidence. If children tend to be efficient, why do they not use multiplication but instead do quite a lot of counting or adding? Several explanations can be suggested: They are not able to identify the structure of a multiplicative word problem as a multiplicative structure, or they do recognize a multiplicative structure but do not know the relevant multiplication facts. In this work we differentiate between these two obstacles by looking not only at children’s solution strategies but also at the way they perceive different situations. Most of the existing research, including the works described above, involves word problems. In solving word problems children are engaged in text interpretation, a stage which might contribute to the difficulty in identifying the efficient structure (although in some word problem types the verbal description contains clues for identifying a multiplicative structure). In this work we avoid this stage by looking at children’s behavior in different non-contextual displays of objects. As we show 2 below, the use of a multiplicative structure is scarce even in these noncontextual tasks. PROCEDURE Fifty four third and forth grade Israeli children were individually interviewed. The children were chosen from regular classes that use the same curriculum, called “One-two-and three”. They were identified by their teacher as having some minor difficulties in mathematics. This curriculum usually introduced beginning ideas about multiplication at the end of first grade, and further develops the concept in second grade. A sequence of concrete models is used in order to represent multiplication: a “train” of equal rods, the same rods in a rectangular configuration, and eventually an array of dots. Using the array model the children discuss the number of rows and the number of dots in each row, and apply the model in different problem solving situations. The purposes of the interview were: To find what mathematical model children use spontaneously in perceiving a given display, which has a multiplicative structure, to observe which strategy they apply spontaneously in calculating the amount represented in the display, and to find how they calculate multiplication facts in multiplication number problems. Eventually these findings were used to investigate the relation between knowing multiplication facts and recognizing and using multiplication in different situations. In the course of the interview each child was presented with different displays, asked to describe what she sees, and then requested to find “How many there are”. The order was: Equivalent sets, a “train” of equal rods, a rectangular array, and some contextual situations (involving eyes and fingers). Each display was presented several times with different numbers (4x5, 10x5, 4x2, 10x2). Here we present the results for the case of 4x5, (complete results to be presented in an extended article). The request to describe what they see was intended for investigating how children perceive the display. The child was given a card with a dot configuration and asked to tell the interviewer, who supposedly could not see the card, what to draw. Several additional tasks included: representing a given expression, such as 4x5, using rods, inventing a story problem to a given expression, and finding some multiplication facts, e.g. 4x5. The questions that mentioned multiplication came only at the end of the interview in order to avoid any hints about the choice of an operation in the different displays. 3 RESULTS Children’s conceptions were deduced from their display descriptions and explanations during the interview. In several cases a child was considered to be perceiving the display as a multiplicative structure even when an additive or a counting strategy was used in the calculation of the total amount of objects. In the following excerpt a third grader, Lorry, tries to figure out the total amount represented by a “train” consisting of four ‘5-rod’-s, as shown below: yellow yellow yellow yellow I: What do you see? L: Yellow rods of 5. I: And what else? (no answer) How many rods? L: 4. I: How much is it? L: Should I do 4 multiplied by 5 [note: In Hebrew 4X5 can be read as ’4 multiplied by 5’, or as ‘4 times 5’. Here she used the word ‘multiplied’. Further on when she calculates the amount by addition, she uses ‘times’]. I: Yes. L: (Thinks for a while) 25. I: How did you do it? L: I did four times five, 5 plus 5 that’s 10, and another 5 that’s 20, and another 5 that’s 25. Table 1 presents the percentages of students who perceived the different displays of 4X5 as multiplicative situations. It also shows these percentages separately for students who could do a mental calculation of 4X5 (using either fact retrieval or repeated addition), and for those who could not do a mental calculation (e.g. had to use objects). It should be noted that the columns are not disjoint. A child who perceived a multiplicative structure in one display, could also see it in another display. Table 1: Children exhibiting multiplicative display conceptions. display calculation mental n=32 non-mental n=22 all students n=54 equal sets yes no 7 25 (22%) (78%) 0 22 (0%) (100%) 7 47 (13%) (87%) rods yes 5 (16%) 2 (9%) 7 (13%) no 27 (84%) 20 (91%) 47 (87%) array yes no 10 22 (31%) (69%) 2 20 (9%) (91%) 12 42 (22%) (78%) 4 The data in Table 2 shows the different calculation strategies in each of the displays for children who could figure out 4x5 mentally. This subgroup of children includes those who could potentially utilize their knowledge in the different displays. Table 2: Strategy choice in different situations for children who could mentally multiply 4x5. Strategy Situation equal sets rods rectangular array contextual cases multiplication 6 (19%) 4 (13%) 8 (25%) 7 (22%) addition counting 18 (56%) 19 (59%) 9 (28%) 20 (63%) 6 (19%) - other 9 (28%) 3 (9%) 2 (6%) 9 (28%) 6 (19%) 2 (6%) total 32 (100%) 32 (100%) 32 (100%) 32 (100%) As can be seen in Table 2, less than a quarter of the children who calculated 4x5 mentally, used multiplication in each of the different display calculations. Our data (not presented here) details this distribution separately for children who did the calculation of 4x5 by retrieval, and those who used addition. Most of the children who used multiplication in the display calculation were those who used it in the calculation of 4x5. Children’s answers and explanations contribute some interesting information on the way they perceive the given representations. The following are two of these examples: 1. Post hoc identification of a multiplicative structure: Given a rectangular array of 4x5 X-s , Ron (a forth grader) draws it correctly from memory. The task is followed by this dialog: How many rows are there? 4 How many X-s are there in each row? 5 How many X-s altogether? (Ron thinks for quite a while) 20 How could you tell? I did 4x5. Did you do it in your head? No. I counted the X-s. So why did you say 4x5? Because it’s 20. But 2x10 is also 20. (Ron hesitates a moment) Ah! But here (in the array) we have 4 and also 5. So why did you count earlier rather than do 4x5? Because I was in a hurry... 5 This dialog might initially suggest that Ron identified the multiplicative structure, or at least the repeated addition structure of the array. However, the time it took him to figure out the total amount, his own account on his counting, and his surprised discovery of the connection to the 4 and 5 lead to a different interpretation. Ron suggested the expression 4x5 after counting 20 X-s in the display. He might have chosen 4x5 because it is an expression that yields 20. It is probably during the discussion that he suddenly saw how the array dimensions related to the expression. 2. A selective application of multiplication: Some children used addition or even counting for small amounts, while applying multiplication for larger amounts. Other children had different reasons for the choice of a strategy, such as: I counted [even though I used multiplication in another situation] because I was in a hurry.... [and would have wasted time if I stopped to analyze the situation]. DISCUSSION Third and forth grade children participating in this study showed very little use of multiplication strategies in non-contextual displays, while multiplication was the more efficient strategy. These findings could only partially be attributed to the fact that most of these children did not know the relevant multiplication facts. This was revealed by investigating the way children perceive the displays. Only a small proportion of children perceived the displays as multiplicative structures. Even among those who could figure out a multiplication fact mentally, only about a third identified the multiplicative structures. The conclusion that the blame does not lie in absent knowledge of facts is also manifested by the choice of strategies in figuring the amount in different displays. Less than a quarter of the children who could figure out the facts mentally used multiplication, a large proportion of them used addition, and some even counted. The children in this study were identified by their teachers as having some difficulties. Yet the displays presented to them were familiar representations, the same ones through which multiplication was defined to them in first and second grades. If fact retrieval is not the main obstacle in applying multiplication, perhaps the difficulties involve the nature of the displays or the nature of instruction. The identification of a multiplicative structure is quite complex. In equivalent set situations, for example, one has to be able to perceive all the given sets at the same time and recognize their equivalence. In 6 deriving the number expression one of the factors is an intensive quantity, appearing not just in one set but in each of the sets. The second factor is not even represented as a simple set. Rather, it is the number of the sets in the display. This complexity makes it difficult for children to identify and apply a multiplicative structure in a given situation. The interviews disclose some of the display difficulties. In additional tasks, where children were asked to use manipulatives and represent an expression, such as 3x4, some of them tended to represent both numbers. Thus, for example, one of the children used rods and built a train consisting of a single 4-rod and three 3-rod -s, as follows: (4) (3) (3) (3) When realizing that something was wrong because it does not measure 12, as expected, he changed it to one 3-rod and three 4-rod -s. He was frustrated upon realizing that it still does not measure 12. Another child represented this expression by building an array consisting of four rows, with three 3-rod -s in each row. In the course of class instruction children are directed to those elements in the display which represent the multiplication factors. If we want them to develop the ability to look at a given display and choose an efficient mathematical model, we need to teach them to analyze situation structures and detect relevant features of these situations. Our instruction should include tasks that give them the opportunity to develop the ability to analyze and apply the mathematical models which are available to them. REFERENCES Carpenter, T. P., Ansell, E., Franke, K. L., Fennema, E., & Weisbeck, L. (1993). Models of problem solving: A study of kindergarten children’s problem-solving processes. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 24, 428-441. Fischbein, E., Deri, M., Nello, M. S., & Merino, M. S. (1985). The role of implicit models in solving verbal problems in multiplication and division. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 16, 3-17. Greer, B. (1992). Multiplication and division as models of situations. In D. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning (pp. 276-295). New York: Macmillan. Kouba, V. L. (1989). Children’s solution strategies for equivalent set multiplication and division word problems. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 20, 2, 147-158. Mitchelmore, M. C., & Mulligan, J. (1996). Children’s developing multiplication and division strategies. Proceedings of the 20th 7 International Conference for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, 3, 407-414. Nesher, P. (1988). Multiplicative school word problems: Theoretical approaches and empirical findings. In J. Hiebert & M. Behr (Eds.), Number concepts and operations in middle grades (pp. 19-40). Reston, VA: NCTM; Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Schwartz, J. (1988). Intensive quantity and referent transforming arithmetic operations. In J. Hiebert & M. Behr (Eds.), Number concepts and operations in middle grades (pp. 41-52). Reston, VA: NCTM; Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Siegler, R. S., & Shrager, J. (1984). Strategy choice in addition and subtraction: How do children know what to do. In C. Sophian (Ed.), Origins of cognitive skills (pp. 229-293). Hillsdale, NJ: LEA. Vergnaud, G. (1983). Multiplicative structures. In R. Lesh & M. Landau (Eds.), Acquisition of mathematics concepts and processes (pp. 128-175). New York: Academic Press. Woods, S. S., Resnick, L. B., & Groen, G. J. (1975). An experimental test of five process models for subtraction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 67, 17-21. 8