Appendix: Mathematical Miscellany

advertisement

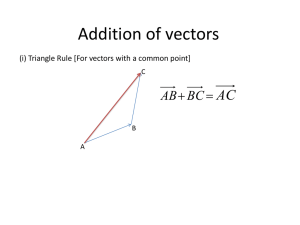

Appendix: Mathematical Miscellany 1. Vector Products The dot and cross products are often introduced via trigonometric functions and/or matrix operations, but they also arise quite naturally from simple considerations of Pythagoras' theorem. Given two points a and b in the three-dimensional vector space with Cartesian coordinates (ax,ay,az) and (bx,by,bz) respectively, the squared distance between these two points is If (and only if) these two vectors are perpendicular, the distance between them is the hypotenuse of a right triangle with edge lengths equal to the lengths of the two vectors, so we have if and only if a and b are perpendicular. Equating these two expressions and canceling terms, we arrive at the necessary and sufficient condition for a and b to be perpendicular This motivates the definition of the left hand quantity as the "dot product" (also called the scalar product) of the arbitrary vectors a = (ax,ay,az) and b = (bx,by,bz) as the scalar quantity At the other extreme, suppose we seek an indicator of whether or not the vectors a and b are parallel. In any case we know the squared length of the vector sum of these two vectors is We also know that S = |a| + |b| if and only if a and b are parallel, in which case we have Equating these two expressions for S2, canceling terms, and squaring both sides gives the necessary and sufficient condition for a and b to be parallel Expanding these expressions and canceling terms, this becomes Notice that we can gather terms and re-write this equality as Obviously a sum of squares can equal zero only if each term is individually zero, which of course was to be expected, because two vectors are parallel if and only if their components are in the same proportions to each other, i.e., which represents the vanishing of the three terms in the previous expression. This motivates the definition of the cross product (also known as the vector product) of two vectors a = (ax,ay,az) and b = (bx,by,bz) as consisting of those three components, ordered symmetrically, so that each component is defined in terms of the other two components of the arguments, as follows By construction, this vector is null if and only if a and b are parallel. Furthermore, notice that the dot products of this cross product and each of the vectors a and b are identically zero, i.e., As we saw previously, the dot product of two vectors is 0 if and only if the vectors are perpendicular, so this shows that a b is perpendicular to both a and b. There is, however, an arbitrary choice of sign, which is conventionally resolved by the "right-hand rule". It can be shown that if is the angle between a and b, then ab is a vector with magnitude |a||b|sin() and direction perpendicular to both a and b, according to the righthand rule. Similarly the scalar ab equals |a||b|cos(). 2. Differentials In Chapter 5.2 we gave an intuitive description of differentials such as dx and dy as incremental quantities, but strictly speaking the actual values of differentials are arbitrary, because only the ratios between them are significant. Differentials for functions of multiple variables are just a generalization of the usual definitions for functions of a single variable. For example, if we have z = f(x) then the differentials dz and dx are defined as arbitrary quantities whose ratio equals the derivative of f(x) with respect to x. Consequently we have dz/dx = f '(x) where f '(x) signifies the partial derivative z/x, so we can express this in the form In this case the partial derivative is identical to the total derivative, because this f is entirely a function of the single variable x. If, now, we consider a differentiable function z = f(x,y) with two independent variables, we can expand this into a power series consisting of a sum of (perhaps infinitely many) terms of the form Axmyn. Since x and y are independent variables we can suppose they are each functions of a parameter t, so we can differentiate the power series term-by-term, with respect to t, and each term will contribute a quantity of the form where, again, the differentials dx,dy,dz,dt are arbitrary variables whose ratios only are constrained by this relation. The coefficient of dy/dt is the partial derivative of Axmyn, with respect to y, and the coefficient of dx/dt is the partial with respect to x, and this will apply to every term of the series. So we can multiply through by dt to arrive at the result The same approach can be applied to functions of arbitrarily many independent variables. 3. Differential Operators The standard differential operators are commonly expressed as formal "vector products" involving the ("del") symbol, which is defined as where ux, uy, uz are again unit vectors in the x,y,z directions. The scalar product of with an arbitrary vector field V is called the divergence of V, and is written explicitly as The vector product of with an arbitrary vector field V is called the curl, given explicitly by Note that the curl is applied to a vector field and returns a vector, whereas the divergence is applied to a vector field but returns a scalar. For completeness, we note that a scalar field Q(x,y,z) can be simply multiplied by the operator to give a vector, called the gradient, as follows Another common expression is the sum of the second derivatives of a scalar field with respect to the three directions, since this sum appears in the Laplace and Poisson equations. Using the "del" operator this can be expressed as the divergence of the gradient (or the "div grad") of the scalar field, as shown below. For convenience, this operation is often written as 2, and is called the Laplacian operator. All the above operators apply to 3-vectors, but when dealing with 4-vectors in Minkowski spacetime the analog of the Laplacian operator is the d'Alembertian operator 4. Differentiation of Vectors and Tensors The easiest way to understand the motivation for the definitions of absolute and covariant differentiation is to begin by considering the derivative of a vector field in threedimensional Euclidean space. Such a vector can be expressed in either contravariant or covariant form as a linear combination of, respectively, the basis vectors u1, u2, u3 or the dual basis vectors u1, u2, u3, as follows where Ai are the contravariant components and Ai are the covariant components of A, and the two sets of basis vectors satisfy the relations where gij and gij are the covariant and contravariant metric tensors. The differential of A can be found by applying the chain rule to either of the two forms, as follows If the basis vectors ui and ui have a constant direction relative to a fixed Cartesian frame, then dui = dui = 0, so the second term on the right vanishes, and we are left with the familiar differential of a vector as the differential of its components. However, if the basis vectors vary from place to place, the second term on the right is non-zero, so we must not neglect this term if we are to allow curvilinear coordinates. As we saw in Part 2 of this Appendix, for any quantity Q = f(x) and coordinate xi we have so we can substitute for the three differentials in (1) and re-arrange terms to write the resulting expressions as Since these relations must hold for all possible combinations of dxi , the quantities inside parentheses must vanish, so we have the following relations between partial derivatives If we now let Aij and Aij denote the projections of the ith components of (2a) and (2b) respectively onto the jth basis vector, we have and it can be verified that these are the components of second-order tensors of the types indicated by their indices (superscripts being contravariant indices and subscripts being covariant indices). If we multiply through (using the dot product) each term of (2a) by ui, and each term of (2b) by ui, and recall that uiuj = ij, we have For convenience we now define the three-index symbol which is called the Christoffel symbol of the second kind. Although the Christoffel symbol is not a tensor, it is very useful for expressing results on a metrical manifold with a given system of coordinates. We also note that since the components of uiuj are constants (either 0 or 1), it follows that (uiuj)/xk = 0, and expanding this partial derivative by the chain rule we find that Therefore, equations (3) can be written in terms of the Christoffel symbol as These are the covariant derivatives of, respectively, the contravariant and covariant forms of the vector A. Obviously if the basis vectors are constant (as in Cartesian or oblique coordinate systems) the Christoffel symbols vanish, and we are left with just the first terms on the right sides of these equations. The second terms are needed only to account for the change in basis with position of general curvilinear coordinates. It might seem that these definitions of covariant differentiation depend on the fact that we worked in a fixed Euclidean space, which enabled us to assign absolute meaning to the components of the basis vectors in terms of an underlying Cartesian coordinate system. However, it can be shown that the Christoffel symbols we've used here are the same as the ones defined in Section 5.4 in the derivation of the extremal (geodesic) paths on a curved manifold, wholly in terms of the intrinsic metric coefficients gij and their partial derivatives with respect to the general coordinates on the manifold. This should not be surprising, considering that the definition of the Christoffel symbols given above was in terms of the basis vectors uj and their derivatives with respect to the general coordinates, and noting that the metric tensor is just gij = uiuj . Thus, with a bit of algebra we can show that in agreement with Section 5.4. We regard equations (4) as the appropriate generalization of differentiation on an arbitrary Riemannian manifold essentially by formal analogy with the flat manifold case, by the fact that applying this operation to a tensor yields another tensor, and perhaps most importantly by the fact that in conjunction with the developments of Section 5.4 we find that the extremal metrical path (i.e., the geodesic path) between two points is given by using this definition of "parallel transport" of a vector pointed in the direction of the path, so the geodesic paths are locally "straight". Of course, when we allow curved manifolds, some new phenomena arise. On a flat manifold the metric components may vary from place to place, but we can still determine that the manifold is flat, by means of the Riemann curvature tensor described in Section 5.7. One consequence of flatness, obvious from the above derivation, is that if a vector is transported parallel to itself around a closed path, it assumes its original orientation when it returns to its original location. However, if the metric coefficients vary in such a way that the Riemann curvature tensor is non-zero, then in general a vector that has been transported parallel to itself around a closed loop will undergo a change in orientation. Indeed, Gauss showed that the amount of deflection experienced by a vector as a result of being parallel-transported around a closed loop is exactly proportional to the integral of the curvature over the enclosed region. The above definition of covariant differentiation immediately generalizes to tensors of any order. In general, the covariant derivative of a mixed tensor T consists of the ordinary partial derivative of the tensor itself with respect to the coordinates xk, plus a term involving a Christoffel symbol for each contravariant index of T, minus a term involving a Christoffel symbol for each covariant index of T. For example, if r is a contravariant index and s is a covariant index, we have It's convenient to remember that each Christoffel symbol in this expression has the index of xk in one of its lower positions, and also that the relevant index from T is carried by the corresponding Christoffel symbol at the same level (upper or lower), and the remaining index of the Christoffel symbol is a dummy that matches with the relevant index position in T. One very important result involving the covariant derivative is known as Ricci's Theorem. The covariant derivative of the metric tensor is gij is If we substitute for the Christoffel symbols from equation (5), and recall that we find that all the terms cancel out and we're left with gij,k = 0. Thus the covariant derivative of the metric tensor is identically zero, which is what prompted Einstein to identify it with the gravitational potential, whose divergence vanishes, as discussed in Section 5.8. 5. Notes on Curvature Derivations Direct substitution of the principal q values into the curvature formula of Section 5.3 gives a somewhat complicated expression, and it may not be obvious that it reduces to the expression given in the text. Even some symbolic processors seem to be unable to accomplish the reduction. So, to verify the result, recall that we have where m = (ca)/b. The roots of the quadratic in q are and of course qq' = 1. From the 2nd equation we have q2 = 1 + 2mq, so we can substitute this into the curvature equation to give Adding and subtracting c in the numerator, this can be written as Now, our assertion in the text is that this quantity equals (a+c) + b . If we subtract 2c from both of these quantities and multuply through by 1 + mq, our assertion is Since q = m + the right hand term in the square brackets can be written as bq bm, so we claim that Expanding the right hand side and cancelling terms and dividing by m gives Now we multiply by the conjugate quantity q' to give The quantities bq' cancel, and we are left with m = (c a)/b, which is the definition of m. Of course the same derivation applies to the other principle curvature if we swap q and q'. Section 5.3 also states that the Gaussian curvature of the surface of a sphere of radius R is 1/R2. To verify this, note that the surface of a sphere of radius R is described by x2 + y2 + z2 = R2, and we can consider a point at the South pole, tangent to a plane of constant z. Then we have Taking the negative root (for the South Pole), factoring out R, and expanding the radical into a power series in the quantity (x2 + y2) / R2 gives Without changing the shape of the surface, we can elevate the sphere so the South pole is just tangent to the xy plane at the origin by adding R to all the z values. Omitting all powers of x and y above the 2nd, this gives the quadratic equation of the surface at this point Thus we have z = ax2 + bxy + cx2 where from which we compute the curvature of the surface as expected. 6. Odd Compositions It's interesting to review the purely formal constraints on a velocity composition law (such as discussed in Section 1.8) to clarify what distinguishes the formulae that work from those that don't. Letting v12, v23, and v13 denote the pairwise velocities (in geometric units) between three co-linear particles P1, P2, P3, a composition formula relating these speeds can generally be expressed in the form where f is some function that transforms speeds into a domain where they are simply additive. It's clear that f must be an "odd" function, i.e., f(-x) = -f(x), to ensure that the same composition formula works for both positive and negative speeds. This rules out transforms such as f(x) = x2, f(x) = cos(x), and all other "even" functions. The general "odd" function expressed as a power series is a linear combination of odd powers, i.e., so we can express any such function in terms of the coefficients [c1,c3,...]. For example, if we take the coefficients [1,0,0,...] we have the simple transform f(x) = x, which gives the Galilean composition formula v13 = v12 + v23. For another example, suppose we "weight" each term in inverse proportion to the exponent by using the coefficients [1, 1/3, 1/5, 1/7,...]. This gives the transform leading to Einstein's relativistic composition formula From the identity atanh(x) = ln[(1+x)/(1x)]/2 we also have the equivalent multiplicative form which is arguably the most natural form of the relativistic speed composition law. The velocity parameter p = (1+v)/(1-v) also gives very natural expressions for other observables as well, including the relativistic Doppler shift, which equals , and the spacetime interval between two inertial particles each one unit of proper time past their point of intersection, which equals p1/4 p-1/4. Incidentally, to give an equilateral triangle in spacetime, this last equation shows that two particles must have a mutual speed of = 0.745... 7. Independent Components of the Curvature Tensor As shown in Section 5.7, the fully covariant Riemann curvature tensor at the origin of Riemann normal coordinates, or more generally in terms of any “tangent” coordinate system with respect to which the first derivatives of the metric coefficients are zero, has the symmetries These symmetries imply that although the curvature tensor in four dimensions has 256 components, there are only 20 algebraic degrees of freedom. To prove this, we first note that the anti-symmetry in the first two indices and in the last two indices implies that all the components of the form Raaaa, Raabb, Raabc, Rabcc, and all permutations of Raaab are zero, because they equal the negation of themselves when we transpose either the first two or the last two indices. The only remaining components with fewer than three distinct indices are of the form Rabab and Rabba, but these are the negatives of each other by transposition of the last two incides, so we have only six independent components of this form (which is the number of ways of choosing two of four indices). The only non-zero components with exactly three distinct indices are of the forms Rabac = Rbaac = Rabca = Rbaca, so we have twelve independent components of this form (because there are four choices for the excluded index, and then three choices for the repeated index). The remaining components have four distinct indices, but each component with a given permutation of indices actually determines the values of eight components because of the three symmetries and anti-symmetries of order two. Thus, on the basis of these three symmetries there are only 24/8 = 3 independent components of this form, which may be represented by the three components R1234, R1342, and R1432. However, the skew symmetry implies that these three components sum to zero, so they represent only two degrees of freedom. Hence we can fully specify the Riemann curvature tensor (with respect to “tangent” coordinates) by giving the values of the six components of the form Rabab, the twelve components of the form Rabac, and the values of R1234 and R1342, which implies that the curvature tensor (with respect to any coordinate sytem) has 6 + 12 + 2 = 20 algebraic degrees of freedom. The same reasoning can be applied in any number of dimensions. For a manifold of N dimensions, the number of independent non-zero curvature components with just two distinct indices is equal to the number of ways of choosing 2 out of N indices. Also, the number of independent non-zero curvature components with 3 distinct indices is equal to the number of ways of choosing the N-3 excluded indices out of N indices, multiplied by 3 for the number of choices of the repeated index. This leaves the components with 4 distinct indices, of which there are 4! times the number of ways of choosing 4 of N indices, but again each of these represents 8 components because of the symmetries and anti-symmetries. Also, these components can be arranged in sets of three that satisfy the three-way skew symmetry, so the number of independent components of this form is reduced by a factor of 2/3. Therefore, the total number of algebraically independent components of the curvature tensor in N dimensions is