Lesson 1

Was Bluebeard Just a Lucky Pirate?

Vectors, Maps, and the Global Positioning System

Developed by: Megan Schnorenberg

Overview

We use vectors every day when we talk about physical quantities which have direction; for example when we talk about velocity, acceleration, or even weight. Vectors are an integral part of math, physics, and engineering, and since vectors can be easily represented in two-dimensions using the coordinate plane, vectors are easy for students to visualize. This unit introduces the concept of a vector in

Lesson 1, then in Lesson 2 has students become treasure hunters and follow a set of vectors (where vectors are represented by an angular direction – using a compass – and a magnitude) which lead to a treasure chest, thus learning compass use, practicing vector notation, and interpreting vectors as they apply to everyday situations. Lesson 3 has students becoming the pirates as they create vector treasure maps for their colleagues to follow, gaining a deeper understanding of how vectors work. As they apply these vector concepts to actual maps while practicing triangulation in Lesson 4, students begin to understand one of the many uses of vectors today.

Topics

Basic vector arithmetic

Map Reading

Latitude and Longitude

Compass/GPS usage

Lessons and Activities within the Unit:

Applications of vectors

Representing vectors both arithmetically and graphically

Applications of vectors

1.

Just the Basics: What’s in a Vector? a.

Activity One - Why We Need Vectors b.

Activity Two - Speak Vector to Me!

2.

Bluebeard’s Treasure Hunt. (Learning the basic concepts of vectors and applying those concepts by following a ‘treasure map’ of vector directions.) a.

Pre-Activity One - Getting from point a to point b: Vectors in the Classroom b.

Pre-Activity Two - A Crash Course in Compass Use

Page 1 of 18

c.

Pre-Activity Three - Compass Scavenger Hunt d.

Main Activity – Finding Bluebeard’s Treasure

3.

Becoming a Pirate: How to Make a Treasure Map (Making our own vector treasure map for others to follow.) a.

Pre-Activity: How to Shoot a Bearing like a Sharp-Shooter b.

Main Activity – Creating a Map

4.

Bluebeard meets Carmen San Diego (Applying the idea of vectors to map triangulation by learning to shoot bearings) a.

What’s in a Map? b.

A Spiderweb of Triangulation

Standards and Benchmarks: (Wyoming Mathematical Content and Performance Standard

MA7.3.1 – Students apply estimation and measurement of length to content problems and convert, within the U.S. customary (in, ft, yd, mi) and within the metric system

(mm, cm, m, km).

MA7.3.6 – Students measure angles with a protractor

MA7.4.4 – Students understand and use basic concepts of the coordinate system, including plotting points in all four quadrants.

MA7.2.3 – Students communicate the reasoning used in indentifying geometric relationships in problem-solving saturations appropriate to grade level.

MA8.2.4 – Students use geometric formulas including the Pythagorean Theorem.

MA8.2.5 – Students represent geometric figures using a rectangular coordinate plane.

MA11.2.2 – Students communicate, using mathematical language to:

Interpret, represent, or create geometric figures;

Draw or build figures from a mathematical description;

Analyze properties and determine attributes of 2- and 3- dimensional objects.

MA11.2.4 – Students solve problems involving the coordinate planes such as the distance between two points, the midpoint, and the slope.

MA11.2.5 – Students connect geometry with other mathematical topics.

Page 2 of 18

Lesson 1

The Basics: What’s in a Vector?

Developed by Megan Schnorenberg

Grade Level: 7-12

Topics Covered:

Estimated Time:

Definition of a vector

45-60 minutes

Representing vectors graphically

Adding and subtracting vectors (algebraically and graphically)

Multiplying vectors by a scalar (algebraically and graphically)

Representing two-dimensional vectors using rectangular coordinates,

Representing two-dimensional vectors using cylindrical coordinates (i.e. by degree and magnitude)

Goals:

Students will understand the concept of a vector and be able to perform basic vector operations

(addition, subtraction, scalar multiplication).

Students will be able to draw vectors on the coordinate plane and graphically add, subtract, and multiply by a scalar.

Students will be able to decompose vectors into components along the directions of given axes in two-dimensions.

Students will be able to combine vector components into a magnitude and direction.

Vocabulary:

Vector – a geometric object which has both magnitude and direction.

Components – the parts of a vector; generally broken down into a y-component and an x-component which correspond to the x and y axis on the coordinate plane.

Scalar – a number which does not have a direction associated with it

Magnitude – the length of a vector

Resultant – the vector obtained by adding or subtracting two vectors

Page 3 of 18

Knowledge Assumptions:

I.

It is assumed the students’ have a basic understanding of graphing concepts including the following: o Cartesian Coordinate System - also known as the Cartesian plane or the rectangular coordinate system (as opposed to the spherical or cylindrical coordinate system.) consists of two perpendicular real number lines, the x and the y axis. Because the plane consists of two crossed real number lines, it is often known as

R

R

or

R

2 . o Origin – the point of intersection between the two axes o Quadrants – the four sections the axes divide the plane into are known as quadrants o Ordered Pairs – indicate a point on the plane by giving an x-coordinate (the first coordinate) and a y-coordinate (the second coordinate.)

II.

It is also assumed students are capable of plotting points on the plane.

Background Information

Vectors play an important role in physics: velocity, acceleration, and force all can be interpreted as vectors since they have both a magnitude and a direction. Vectors can be added, subtracted, multiplied by a scalar in ways similar to regular numbers, and vector operations obey the familiar algebraic laws of commutativity, associativity, and distribution. The sum of two vectors with the same initial point can be found geometrically using the parallelogram law while multiplication by a positive number, or scalar is really changing the magnitude (or length) of vector. Multiplication by the scalar -1 preserves the magnitude of a vector but reverses its direction. The Cartesian Coordinate System provides a systematic way of describing vectors and operations on them both algebraically and graphically. In two-dimensions, we use the x

y

plane, and vectors become a ‘two-tuples’ of two real numbers, a vector’s x

and y scalar components. We can also represent vectors as their magnitude and their angle from some point of reference.

Activity 1: Why We Need Vectors.

Materials:

A Cartesian coordinate plane

Page 4 of 18

Procedure:

To be discussed in class:

We notice that some physical quantities have a direction associated with them as well as a quantity. For example, when we talk about how fast something is moving, we often want to know the direction in which it is moving: i.e. the car is moving south at 25 meters per second. We need to describe quantities like these with both an amount (also called the magnitude) and a direction or angle.

A quantity that has both magnitude and direction is a vector.

A quantity without direction is a scalar.

Student Question: What types of things can be thought of as vectors?

Possible Answers: Velocity (the car was going north (a direction) at 25 mph (a magnitude).)

Directions (go 20 feet (a magnitude) toward your right (a direction).)

Vectors allow us to represent velocities: For example, say we are flying an airplane into a head wind. As the plane flies, the wind is slowing the velocity of the plane, so how can we know how we are progressing relative to the ground? Vectors help answer that. Vectors help answer that.

Similarly, forces, accelerations, magnetic fields from several sources, all are added like vectors. Engineers who put up a bridge or a building and want to make sure all forces balance so the bridge or building won’t fall down need vectors.

Talking about Vectors

When we talk about vectors, we want to be able to distinguish them from ‘ordinary numbers’, which we call scalars. We do this by marking a vector with an arrow above it: v

is a variable which is just a plain old scalar, while

v

is a vector. The simplest kind of vector is a displacement vector, which shows how far and in which direction something moved. For example, say a pirate ship begins in Belize and travels to

Jamaica. The vector which represents the pirate ship’s displacement will have magnitude approximately

800 kilometers (the distance from Belize to Jamaica) and direction east. We can represent this vector by drawing an arrow from Belize to Jamaica. Now say the pirate ship travels from Jamaica to Panama. The vector representing the ship’s displacement as it moves from Jamaica to Panama will be a vector with magnitude 700km and direction south. (See map included in the accompanying power point.)

Page 5 of 18

Student Question: If you are the first mate on the pirate ship and your captain asks you how far away you now are from Belize, what will you tell him?

Answer: We can use the Pythagorean Theorem to calculate the distance:

800

2

700

2

1063

, so we are 1063 kilometers away.

Student Question: What if the captain asks you if you could have plotted a course directly from Belize to

Panama? Can you come up with a vector which goes from Belize to Panama?

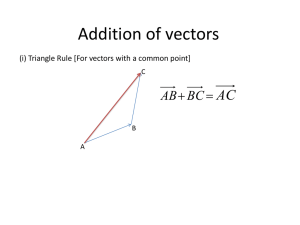

This is how we graphically add vectors – by setting them ‘tip-to-tail’ and finding the resultant vector which goes from the tail of the first vector to the tip of the second vector. Note that it doesn’t make any difference which of the two is added first and which second.

Using the idea of ‘tip-to-tail’ adding, we can resolve a vector into its ‘components’. We will be talking about two-dimensional vectors, so generally we want to talk about vectors in terms of their x

and y components.

We can decompose a vector into its x

and y components by setting its tail at the origin and looking at the ordered pair where its tip is. (See the PowerPoint for examples.) Thus we often write vectors as x , y

, where x

shows how far we travel in the x

-direction and y

shows how far we travel in the y

-direction.

(Note that this is different from the ordered pair

as it indicated we are traveling in a straight line from the origin to the tip of the vector – it has both a magnitude and a direction.) Using this idea, we can add vectors by adding their components; this idea matches up perfectly to the graphical picture.

Student Question: What would it look like to subtract one vector from another?

Answer: If we subtract one vector from another, we simply reverse the direction of the vector we wish to subtract (i.e. make the tail the tip and the tip the tail) and then add this new vector in the normal way.

Subtraction is done ‘tail-to-tail’ by connecting two vectors at their tails and then finding the resultant vector between them. Note that when subtracting vectors it is easier to think in terms of ‘adding a negative’ of the vector you wish to subtract.

Page 6 of 18

How else can we represent vectors?

Mini-Activity: Speak Vector to Me!

Objective: Introduce students to the angle-magnitude form of a vector.

Procedure: Stand at the front of the room and tell the students you only understand vectorspeak; that is you can follow directions given in terms of a vector, but can’t understand anything else. Tell the students that they must direct you from the front of the classroom out the classroom door (without running you into anything).

Remind students that a vector is anything that has magnitude and direction. (If students are having trouble, have them consider the following examples: “Take

two steps left”, “take three hops toward the door”, “walk north ten feet”, etc.)

Evaluate: What are some of the typical direction words we use every day, say when reading maps? (Ideally this will get students thinking about using the cardinal directions

when giving vector directions.)

Page 7 of 18

Lesson 2

Bluebeard’s Treasure Hunt

Developed by Megan Schnorenberg

Adapted from the lessons of Bernie Schnorenberg

Grade Level: 9-12

Topics Covered:

Estimated Time:

Basic Vector Arithmetic

Applications of Vectors

Compass use

30-45 minutes in-class

30-45 minutes following a vector map

Goals:

Students will understand the concept of a vector and be able to perform basic vector operations

(addition, subtraction, scalar multiplication).

Students will be able to recognize applications of vectors outside of mathematics. (i.e. in physics, geography, etc.)

Students will be able to use a compass to follow vector directions.

Vocabulary:

(Review from Lesson 1) Vector – a geometric object which has both magnitude and direction.

(Review from Lesson 1) Components – the parts of a vector; generally broken down into a y-component and an x-component which correspond to the x and y axis on the coordinate plane.

(Review from Lesson 1) Scalar – a number which does not have a direction associated with it

(Review from Lesson 1) Magnitude – the length of a vector

(Review from Lesson 1) Resultant – the vector obtained by adding or subtracting two vectors

Compass - a navigational instrument that indicates the direction to the magnetic poles

Materials:

Red, Blue, Green, and Yellow Balloons (4 of each) with the words “there be treasure here” written on them

(one word per balloon)”

Page 8 of 18

Compasses – One per student or student group

Treasure Map – One per student or student group

Treasure Chest (or something signifying the treasure at the end of the map) – One per student or student group

Preparation:

Prior to providing the students with a vector treasure map to follow, one must be developed. This can be done by following the procedure in Lesson 3 and can be tailored based on location and time. In order to keep things simple, try to keep your vectors from crossing as students follow the directions. (See Appendix

B for an example.)

Procedure:

Engage:

As everyone knows, a pirate is only as good as his or her treasure, and a treasure is only as good as its hiding point, and a hiding place, of course, is only as good as the map which allows you to find it again. In this lesson, we will examine one way of giving good directions to a treasure.

Explore: What does it mean to give directions in terms of a vector?

Pre-Activity One: Getting from point a to point b: Vectors in the classroom

Objective: Help students understand the concept of ‘following’ a vector.

Procedure: A vector can be anything which has both direction and magnitude, for example the statement ‘take three steps towards the front of the room’ can be thought of as a vector with magnitude ‘3-steps’ and direction ‘toward the front of the room’. With this in mind, give the students several vector directions in this fashion, then have them break into pairs. Have each pair practice giving vector directions in navigating around the classroom.

Explain:

Pre-Activity Two: A Crash-Course in Compass Use.

Objective: Give students a basic understanding of how to use a compass.

Page 9 of 18

Procedure: Use the picture in Appendix C to explain the parts of a compass and how a compass works; i.e. the red part of the compass needle is always pointing towards the earth's magnetic north pole, so if you want to go north, turn the compass housing until the N

(for north) and the direction arrow are aligned, hold the compass level, and turn your body until the compass needle and the direction of travel arrow are in a line. You are now facing north. If you want to go in a direction other than north, turn the compass housing so that the direction you wish to go is lined up with direction of travel arrow, hold the compass level, and turn your body until the red compass needle is inside the orienting arrow, (the red needle should be pointing directly at N). The travel arrow is now facing the direction in which you want to go.

Have the students find various directions and practice walking in specific directions, being careful to keep the compass level as they walk and checking often that they are on course.

Pre-Activity Three: Compass Scavenger Hunt

Objective: Give students a basic understanding of how to use a compass.

Procedure: Set up a mini-courses for students to practice on; Split the students into 4 groups and give each group one of the following ‘Treasure Maps’ on a piece of paper, telling them to follow the ‘map’ and collect the balloon in their groups color at each stop.

Group One – red group Group Three – green group

0 degrees - 10 steps

225 degrees – 14 steps

90 degrees – 20 steps

225 degrees – 14 steps

Group Two – blue group

180 degrees - 10 steps

45 degrees – 14 steps

270 degrees – 20 steps

45 degrees – 14 steps

90 degrees - 10 steps

315 degrees – 14 steps

180 degrees – 20 steps

315 degrees – 14 steps

Group Four – yellow group

270 degrees - 10 steps

135 degrees – 14 steps

0 degrees – 20 steps

135 degrees – 14 steps

Page 10 of 18

Note: To set up this the balloons for each group, simply place one balloon of each color (with the words inside) ten steps away from the starting point in each of the cardinal directions,

north, south, east, and west.

Once the students have collected all the balloons of their color, have them pop the balloons and assemble the appropriate pirate phrase from the words inside.

Activity: Finding Bluebeard’s treasure.

Procedure:

Break the students into teams of three or four, give each the list of vector directions and have them use their compasses to follow them to the treasure chest. (It will be helpful to stagger the start of each group and space the groups out enough that they cannot simply follow in the footsteps of the group ahead of them. Alternately, different maps may be made for each group.)

Elaborate:

After students have successfully located their treasure chest, ask them what was difficult in the activity. How did they overcome those difficulties? (Expect answers such as “It was hard to keep the compass level” or “I wanted to just go straight to the treasure chest!” or “If we messed up one of the

directions, our whole map got messed up.”)

Evaluate:

After discussing the activity, have the students draw a vector representation of the path they took on graph paper, then figure out the resultant vector which would lead them directly from their initial starting point to the treasure chest. (See Appendix A for an example.) Have them think about the following questions:

Why didn’t we just give the resultant vector as a direction to our treasure?

Possible Answer: There were ‘things’ (trees, rocks, buildings etc.) in our way!

Why would a vector map be more useful than one based on landscape features, i.e. “go 12 paces past the giant tree and take a left at the rock that looks like a barnacle?

Possible Answer: Landscapes could change with time.

Page 11 of 18

Lesson 3

Becoming a Pirate: How to Make a Treasure Map

Developed by Megan Schnorenberg

Adapted from the lessons of Bernie Schnorenberg

Grade Level: 9-12

Topics Covered:

Estimated Time:

Basic vector arithmetic

Applications of vectors

Representing vector graphically

30-45 minutes in-class preparing maps

30-45 minutes testing maps (optional)

Compass use

Goals:

Students will understand the concept of a vector and be able to perform basic vector operations

(addition, subtraction, scalar multiplication).

Students will be able to recognize applications of vectors outside of mathematics. (i.e. in physics, geography, etc.)

Students will be able to use a compass to follow vector directions.

Students will be able to use a compass and create vector directions which classmates can successfully follow.

Vocabulary:

(Review from Lesson 1) Vector – a geometric object which has both magnitude and direction.

(Review from Lesson 1) Components – the parts of a vector; generally broken down into a y-component and an x-component which correspond to the x and y axis on the coordinate plane.

(Review from Lesson 1) Scalar – a number which does not have a direction associated with it

(Review from Lesson 1) Magnitude – the length of a vector

(Review from Lesson 1) Resultant – the vector obtained by adding or subtracting two vectors

Page 12 of 18

(Review from Lesson 2) Compass - a navigational instrument that indicates the direction to the magnetic poles

Bearings - the direction one object is from another object

Materials and Preparation:

Compasses – 1 per student or student group

Graph Paper and Pencils

Optional: Treasure chests for students to hide (one per group)

Procedure:

Pre-Activity – How to Shoot a Bearing like a Sharp-Shooter

Objective: A compass is used primarily to ‘shoot a bearing’ from your current position toward someplace you want to head towards. A bearing is a horizontal angle which is measured clockwise from north to some point in the real world. In this activity, we will practice shooting a bearing to determine a direction as well as walking a bearing; that is following a bearing to get where you want to go.

Procedure: Use the following steps to explain shooting bearings to students, then have them break into partners and practice shooting and walking bearings.

Shooting a Bearing

1) First, to shoot a bearing, point the compass’s ‘travel arrow’ to the place you wish to go. Make

sure you keep the compass level as you do this!

2) Next, rotate the compass housing until the north orienting arrow of the compass housing lines up with the red magnetic needle. (i.e. get the red arrow inside the red arrow shape)

3) Read the bearing (in degrees) by looking at where the degree dial is lined up with the direction of travel arrow. Congratulations! You just shot a bearing!

Walking a Bearing

1) After you’ve taken a bearing, you most likely will want to head in the direction of your bearing. Holding the compass as level as possible, line up the degrees of the bearing with the direction of travel area.

Page 13 of 18

2) Rotate your whole body (still holding the compass level!) until the red magnetic needle is in the red arrow shape. (You should be facing in the direction of the direction of travel arrow.)

3) Try to find some kind of feature of the land (like a particular tree or an easily distinguished rock feature) that lies along your bearing and walk toward that feature as you continue to check your compass.

Activity – Creating Your Own Treasure Map!

Objective: Students will practice shooting bearings and writing vector directions as they create their own treasure maps.

Procedure: Inform students they are going to create their own treasure maps for other students to follow by creating a list of vector directions which will start at a specific location and lead to a treasure. Break students into groups of 2-4 people and have them use the following procedure to create their maps: (See Student Handout Packet)

Create a starting point: Where will your map start? Be sure to include a starting position!

Create a standard of measurement: Think about the units you will use in your directions – will you use feet, meters, inches, or make up your own unit: for example giant hops or skips.

Make sure if you create your own unit of measurement it is something other groups can easily duplicate and use.

Shoot and record your bearings! Once you are at your starting location, decide which direction you want your treasure hunters to go and shoot a bearing in the direction

Determine Distance: Figure out how far you want your map-readers to travel in the direction of your bearing. Use your standard of measurement to record that distance.

Repeat! Continue shooting bears measuring distances until you reach a location you want to hide your treasure! (Your vector map should include at least 5 vector directions.)

Things to Think About: o How will you go around objects in your treasure hunt? (For example, say you want to direct your map-readers around a tree or a building.) o How will your map-readers know they have reached their ‘treasure’. Make sure you leave something for your direction-followers to find!

Test Your Map ONE: Once you have completed your map and hidden your treasure, return to your staring point and follow your own map to make sure it makes sense!

Page 14 of 18

Test Your Map TWO: Using graph paper, plot out your vectors and then determine the resultant vector. Now return to the starting point of your map and try to follow your resultant vector. Does it get you to your treasure? (Be sure to indicate some type of scale on your drawing.)

Page 15 of 18

Lesson 4

Bluebeard meets Carmen San Diego

Developed by Megan Schnorenberg

Grade Level: 6-12

Topics Covered:

Estimated Time:

Map Reading

Graphing Vectors (grades 8-12)

45 minutes

Goals:

Students will be able to shoot bearings using a compass and a fixed object

Students will be able to triangulate their location on a map by shooting two or more bearings.

Students will be able to represent triangulation on the coordinate plane.

Vocabulary:

(Review from Lesson 1) Vector – a geometric object which has both magnitude and direction.

(Review from Lesson 1) Components – the parts of a vector; generally broken down into a y-component and an x-component which correspond to the x and y axis on the coordinate plane.

(Review from Lesson 1) Scalar – a number which does not have a direction associated with it

(Review from Lesson 1) Magnitude – the length of a vector

(Review from Lesson 1) Resultant – the vector obtained by adding or subtracting two vectors

(Review from Lesson 2) Compass - a navigational instrument that indicates the direction to the magnetic poles

(Review from Lesson 3) Bearings - the direction one object is from another object

Triangulation - process of pinpointing the location of something by taking bearings to it from two remote points.

Map Legend – describes the symbols and orientation of the map; the map scale is usually included in the legend.

Map Scale -The ratio of distances on a map versus the actual distance in real life.

Materials and Preparation:

Page 16 of 18

Compasses – preferably one per student

Several long pieces of string or yarn

Large piece of paper

Local map (optional)

Procedure:

Engage: Have you ever been somewhere that you don’t normally go – say a new city or hiking in the woods – and realized you were lost? What could you do to prevent this? (Most students will respond with

bring a map, bring a GPS, bring a compass, ask directions, etc.) What if there was no one around to ask directions; but you, being the smart person that you are, had a map with you. How would you use the map to determine where you were?

Activity One – What’s in a Map?

Objective: To acquaint students with the basic properties of maps.

Procedure: Have the students break into groups and create ‘maps’ of your classroom including all the features they deem relevant; for example desks, tables, doors, etc. Make sure the students decide on a scale for their map and that their map includes a legend.

Once your students have created their classroom maps, ask them how they would use such a map to figure out their location. (Expect answers such as, well, I’d look at what was around me and then find something

similar on the map.) Ask your students what would happen if they were standing by a desk. If there are several desks on the map, how would they know they had the right one? (Expect answers such as, well I’d

look at what else was around and make sure that matched too.) Help the students develop the idea that they need at least two good points of reference (such as distinguishing landmarks) to help them locate themselves on the map.

Activity Two – A Spiderweb of Triangulation

Objective: To acquaint students with the ideas behind triangulation.

Procedure: Stand in the middle of the classroom and tell the students you are lost and need to use a map to locate yourself. Ask them what ‘feature’ of the room they should pick off the map to help locate yourself. When they pick something (say your desk) locate it in the

Page 17 of 18

room and have the students run a piece of string from the desk to you. (This is

representative of shooting a bearing from the desk to you.) Ask the students if this is enough to locate you on the map. (If they say yes, take a few steps forwards or backwards along the same direction as the string and explain that according to the

map, you could be anywhere along the string.) Now ask them to pick another distinguishing feature from the map and run a string from it to you. Where the strings cross represents your location. Explain to the students this is what happens when they shoot two bearings and compare them with the map; they will pinpoint their location!

Now have the students break back up into their map groups from activity one. Have each group go to a different location in the room and use their compasses to shoot bearings., then use strings to plot those bearings on their maps. Do the strings cross the map at their location in the room?

Explore/Evaluate: Ask the students what kind of features they could use on a ‘real’ map to help determine their location. If you have time (and a local map), take them outside and see if they can locate themselves on the map by shooting bearings and practicing triangulation.

Page 18 of 18