Continued_Fraction_Expansion_sqrt2 - It works!

advertisement

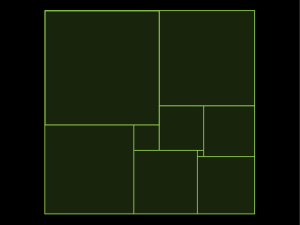

Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . Introduction to continued fractions What is a continued fraction? What is a continued fraction used for? These are questions that are frequently asked when talking about continued fractions. In order to discuss an application of continued fractions we need to first start with some definitions: Definition 1: An expression of the form a0 b0 a1 b1 a2 b2 b3 ... is said to be a continued fraction. The values of the variables can be either real or complex values. There can be either an infinite or a finite number of terms. a3 Definition 2: A simple continued fraction is a continued fraction in which the value of bn = 1 for all n. Definition 3: The terms of a simple continued fraction refer to the value of a1, a2, a3 … For example, a4 is the fourth term. Also referred to as partial quotients. Definition 4 – 5: A finite simple continued fraction is a simple continued fraction with only a finite number of terms. An infinite simple continued fraction is a simple continued fraction with an infinite number of terms. For our discussion on this topic we will try to stick with just simple continued fractions. We will need to know how to evaluate a continued fraction if we want to be able to apply our knowledge to other aspects of mathematics. So let’s start with trying to evaluate a finite simple continued fraction. Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . 1 2 3 1 4 1 5 To start to evaluate this continued fraction we have to start at the bottom 1 and work our way up. First we need to simplify 4 . 5 As we can see we have simplified the denominator 21 of the last fraction to be . We now have a new 5 continued fraction. So we will start with the bottom of that fraction and work our way up. 1 2 1 3 4 1 5 We now have to deal with the case of 1 2 1 1 5 21 21 5 1 . 21 5 Knowing that for any real number the 1 expression refers to the multiplicative a 5 1 inverse of a. So then we know that = . We now have new continued 21 21 5 fraction that we will evaluate in the same way. 3 21 5 2 1 3 5 21 = 2 21 157 1 = 2 = 68 68 68 21 Now that we can evaluate a continued fraction it would be nice to know if we can take a rational number and find its simple continued fraction expansion. 29 Let’s try with the rational number . Let’s first start by writing this 6 improper fraction as a mixed number. We get the following result, 29 5 4 . Since this is not a simple continued fraction, because the 6 6 numerator is not 1, we need a way of rewriting this expression to get a 1 in 5 the numerator. The way to do this is to write as 1 over it’s multiplicative 6 Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . 1 . We can now continue the same 6 5 process to the denominator of the new fraction. The result is, inverse. When we do this we get, 4 1 1 = 4 + [1, 5] = [4; 1, 5] (shorthand notation for the continued 4 6 1 1 5 5 fraction). We can now stop the process since our result is a simple continued fraction. This “iterative” approach of turning a rational number into a simple continued fraction is very effective and efficient. However, there is a graphical method of doing the same process. The rectangle below 31 will represent the fraction . 9 4 Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . (1)Given x = [2; 3, 1, 1, 2] find the value of x using several methods: (a)Find the fraction for x and construct a rectangle with proportions x and verify that this rectangle has a decomposition into 2, then 3, then 1, then 1, and finally into 2 squares. 1 2 1 3 1 41 18 1 1 1 2 The above construction shows a rectangle that was made having sides with lengths 18 and 41. Then the “square decomposition” was done to the rectangle. Two squares (18 x 18) can be placed in the rectangle, now we have another rectangle left over. Three squares (5 x 5) fit into this (second) rectangle. We will continue this process until we have the original rectangle filled with squares. We can see that this rectangle has a decomposition of 2, 3, 1, 1, and 2 squares. Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . The construction that we just did showed that if evaluate a continued fraction and use the numerator and denominator as side lengths of a rectangle then when we decompose the rectangle into squares we will see that the number of subsequent squares that fit in the rectangle will be the same as the numbers in the shorthand notation of the continued fraction 41 expansion of the simplified fraction. We have shown by knowing we can 18 get to [2; 3, 1, 1, 2]. Part (b) of this assignment will go the other way, if we 41 know [2; 3, 1, 1, 2] then we can get to . 18 Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . (b)Construct a moveable rectangle with the decomposition into 2, then 3, then 1, then 1, and finally 2 squares and find the proportions of the resulting rectangle. This construction was done by first making a rectangle where points A and B were moveable. I then constructed a square on side AO, where point O is the origin. Point B was moved until two of those squares (red) could fit. Then in the rectangle left over a square was constructed on the shorter side of the rectangle. Point B was again moved so three of those squares (purple) could fit in the rectangle, this process was repeated until the rectangle is decomposed into 2, then 3, then 1, then 1, then finally 2 squares. We notice that the ordered pair for B is (12.30503, 5.40197) so the sides of the rectangle have lengths 12.30503 and 5.40197. If we divide the length of the longer side of the rectangle by the length of the shorter side of the rectangle you get: 12.30503 2.2778725... 5.40197 If we compare this to the fraction from part (a) of this assignment: 41 2 .2 7 18 We can see that the ratios are almost equivalent; we will say that the cause of this is human error and limitations of computer approximation. We can say that if we know [2; 3, 1, 1, 2] then we can get to in part (a) of this assignment. 41 . This is the converse of what we proved 18 Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . (c)With GeoGebra and a grid build the rectangle backwards starting with two squares of until length. (Rachel and Ed Construction) 5 5 18 5 2 1 18 18 3 1 1 41 This construction was done from then inside out, what is meant by that is the smaller squares were made, then the next larger square, etc… The squares were constructed making sure that the smallest size square had 2 squares, the next size up had 1 square, the next size up had 1 square, the next size up had 3 squares and finally the biggest size square had 2 squares. Now we need to make sure that the sides of the rectangle are in the ratio of 41:8. If we assume the smaller squares are 1 x 1, we can see that the sides of the rectangle formed by this decomposition are in the proportion of 41:18. We 41 have shown three ways of how the decomposition of the fraction can be 18 explained. The practice of simplifying continued fractions is a good mental exercise for students of all ages. Letting students see a graphical representation of a concept is a way for them to make connections that may not have been made before. Lastly multiple representations of the same concept allows learners of all types to better grasp a concept. This lesson can easily be modified to a middle school lesson, I actually taught this lesson Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . to my students last year and they caught on pretty quickly. The group was an 8th grade Geometry class. They were intrigued on how quickly some students could simplify the continued fractions in their heads. This lead to a discussion of reciprocals, adding fractions, mixed numbers, improper fractions. Then the square decomposition was a nice way for the students to get their hands on the math they are studying. We first used graph paper to do the decomposition of the rectangles we then turned to dynamic geometry software to assist in the decomposition of the rectangles. The students always enjoy it when they can get their hands dirty. The last part of the unit was to evaluate periodic continued fractions by using the decomposition of the rectangle. This part of the unit was a great review of properties of radicals and solving quadratic equations. This continued fraction unit is a great unit for reviewing or introducing to Algebra students the concept of ratio and proportion and the use of the quadratic formula. Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . (2)Given x = [1; 2, 1, 2, 1, 2,…] what are the proportions of the rectangle with this periodic decomposition? (a)Argue that the original rectangle must be similar to the red one. Set up proper equations and compute the proportions of the original rectangle. We will first call the shorter side of the whole rectangle 1 and the rest of the longer side of the rectangle we will call x. 1 x x 1 x x Red 1-2x Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . In order for the decomposition to be periodic the red rectangle has to be divided up into 1 and 2 squares with a rectangle left over that can fit 1 and then 2 squares with a rectangle left over that can fit 1 and then 2 squares with a rectangle left over that can fit 1 and 2 squares with a rectangle left over, etc… So we will write a proportion using the corresponding sides of the whole rectangle to the sides of the red rectangle: shorter side 1 1 2x longer side 1 x x Solving this proportion gives us: x 1 3 2 Now if we want to find the proportion of the rectangle we have to find the side length of the longer side of the rectangle. We already know that the shorter side is 1 and the longer side is 1 + x. So by solving 1 + x we get: 1 x 1 1 3 2 1 3 1 3 2 2 2 2 1 3 . The proportion of the 2 rectangle with a rectangle with decomposition of [1; 2, 1, 2, 1, 2 …] is: So the longer side of the rectangle is shorter side 1 2 longer side 1 3 1 3 2 Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . (b)Using the value computed in (a) construct a rectangle and verify that is has the decomposition into one square, then two squares, then one square, then two squares, and so on. We will construct this in GeoGebra by constructing a rectangle with side lengths of 2 and 1 3 . To construct the side of 2 is the easy part, the side of 1 3 needed some thought. Since we need a length of 3 we can use the height of a equilateral triangle whose sides measure 2 units. 300 2 3 600 2 1 First we have to construct an equilateral triangle with side length 2. CD 3 , we are going to call the length of CD b. We will use b as the radius of a circle to construct the side of the triangle than has to be 1 3 . Guy Barmoha 2/28/07 Continued Fraction Expansion of 2 . Now we will construct the rectangle. 1 b 3 2 Now we have to fill the rectangle with squares and see what the decomposition will look like… This rectangle can be divided up into 1 and then 2 squares with a rectangle left over that will fit 1 and then 2 squares with a rectangle left over that will fit 1 and then 2 squares with a rectangle left over that will fit etc…