RATIONAL FOR INTEGRATED PLACEMENT OPTIONS

RATIONALE FOR INTEGRATED PLACEMENT OPTIONS FOR STUDENTS WITH

DISABLITIES

Educational Rationale for Integrated Placement Options for Students with

Disabilities

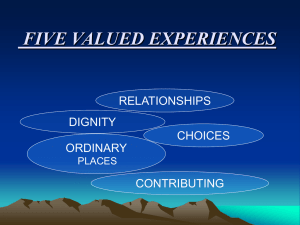

Students’ academic performance was found to be equal or better in inclusive settings in a review of research on inclusion for elementary and secondary schools (Salend &

Duhaney, 1999). Likewise, students who transitioned to middle school after participating in inclusive settings and curriculum from specific feeder schools scored higher on the

FCAT, the Florida state assessment test. In addition, gains were noted for students with and without disabilities in inclusive classrooms in self-esteem, desired behavior, attendance, grades, and test scores (Barnitti, 2002).

Ritter, Michael, and Irby (1999) observed that students with disabilities experienced increased self-esteem due to the sole fact that they were attending classes in a regular education setting, instead of a special education setting.

Legal Rationale for Integrated Placement Options for Students with

Disabilities

First, the law requires that states provide students with disabilities, ages three through 21, a FAPE in the LRE

“Each local educational agency must provide special education and related services to a child with a disability in accordance with the child’s IEP [34 CFR §300.350 (a)]

(Regulations Governing Special Education Programs for Children with Disabilities in

Virginia, 2002). A child with a disability means those persons who are aged two to twenty-one inclusive. Any child who is provided special education and related services is entitled to all rights and protections of the IDEA. These rights and protections include free appropriate public education (FAPE), placement in the least restrictive environment, multidisciplinary evaluation, procedural safeguards, due process, and confidentiality of information.

Second, in order to determine what the most appropriate LRE is for a child,

IEP teams must have a continuum of placement options available from which to choose.

“Each local educational agency shall ensure that a continuum of alternative placements is available to meet the needs of children with disabilities for special education and related services. The continuum must include the alternative placements listed in the definition of special education … and make provision for supplementary services …. “ No single model for the delivery of services to any population or category of children with disabilities will be acceptable for meeting the requirement for a continuum of alternative placements ” [COV §22 1-218] (Regulations Governing Special Education Programs for

Children with Disabilities in Virginia, 2002). IDEA specifies that placement decisions must be made on the individual needs of each child. “Each local educational agency shall ensure that to the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities … are

educated with children without disabilities” [34 CFR §300.550 (b)] (Regulations

Governing Special Education Programs for Children with Disabilities in Virginia, 2002).

Third, IEP teams must document how placement in the regular educational setting with supplementary aids and services is not of educational benefit prior to placing a child in a more restrictive environment.

“…[R]emoval of students with disabilities from the regular educational environment occur only when the nature of severity of the disability is such that education in regular classes with the use of supplementary aids and services cannot be achieved satisfactorily” [IDEA, Section (5) (B)].

“IDEA’s mainstreaming requirement … prohibit[s] a school from placing students with disabilities outside of a regular classroom if educating the child in the regular classroom, with supplementary aids and support services, can be achieved satisfactorily” (Oberti v.

Clementon Board of Education. [3 rd Cir. 1993]). IDEA requires “access to a regular public school classroom” unless there is a compelling educational justification to the contrary” (Tokaricik v. Forest Hills Sch. Dist…, 666 F. 2d 443 (3 rd Cir. 1981).

Daniel R.R. identifies a two prong test to use when determining the least restrictive environment. The first prong asks: whether education in the regular classroom can be achieved satisfactorily with the use of supplemental aids and services? The second prong asks: If placement outside of the regular classroom is necessary for the child to benefit educationally, has the school mainstreamed the child to the maximum extent possible?

Fourth, marginal increases in costs associated with mainstreaming (e.g., staff, inservice training of regular education teachers) cannot be cited as a reason to not provide integrated options to students with disabilities.

IDEA recognizes that regular education personnel are an integral part of the provision of the special education and related services and requires states to provide training to regular education personnel (34 C.F.R. §300.522).

In the Board of Education of Sacramento Unified School District v. Holland, (786 F.

Supp. 874 (E.D. Cal. 1992) case, the District Court concluded that the costs of supplementary aids and services needed to mainstream a child with disabilities was a relevant factor in determining appropriate placement, however, in this case the Court rejected the school district’s suggestion that the mainstreaming requirement would be too costly.

In Greer v. Rome City School District, 18 IDELR 412 (11 th Cir. 1991), the court indicated that merely incurring some additional expenses in placing a child in a regular education environment would not be sufficient to overcome the IDEA’s preference for inclusion.

Rettig v. Kent School District (C79-2234 U.S. Dist. Ct., 1981) adds further clarification to the issue of cost. “It hardly needs to be stated that educational funding is not unlimited, and a school cannot spend an exorbitant amount on one child at the expense of all its

other handicapped students. But the school system does have an obligation to keep abreast of changing educational strategies and implement them where success may be demonstrated.”

Fifth, IEP teams cannot justify a more restrictive placement for a child with disabilities because of a lack of demonstrated academic benefit in a less restrictive environment.

Daniel R. R. specified: “Academic benefits are not mainstreaming’s only virtue. Rather mainstreaming may have benefits in and of itself.”

Sixth, students with disabilities cannot be excluded from regular education settings on the basis of their handicapping condition or any other set criteria.

“The decision as to whether any particular child should be educated in a regular classroom setting, all of the time, part of the time, or none of the time, is necessarily an inquiry into the needs and abilities of one child, and does not extend to a group or category of handicapped students…” (Board of Education of Sacramento Unified School

District v. Holland, 786 F. Supp. 874 (E.D. Cal. 1992).