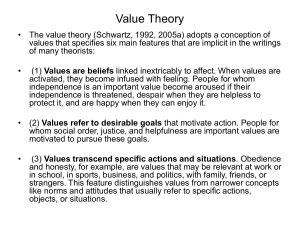

Basic Human Values: Theory, Measurement and

advertisement