Living standards of the total population

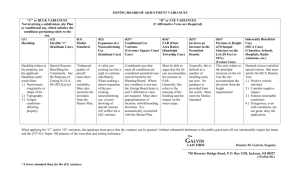

advertisement