Designing Studies: Sampling & Experiments Worksheet

advertisement

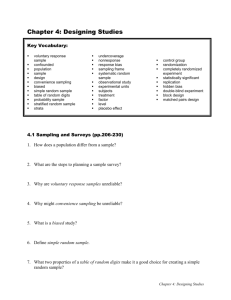

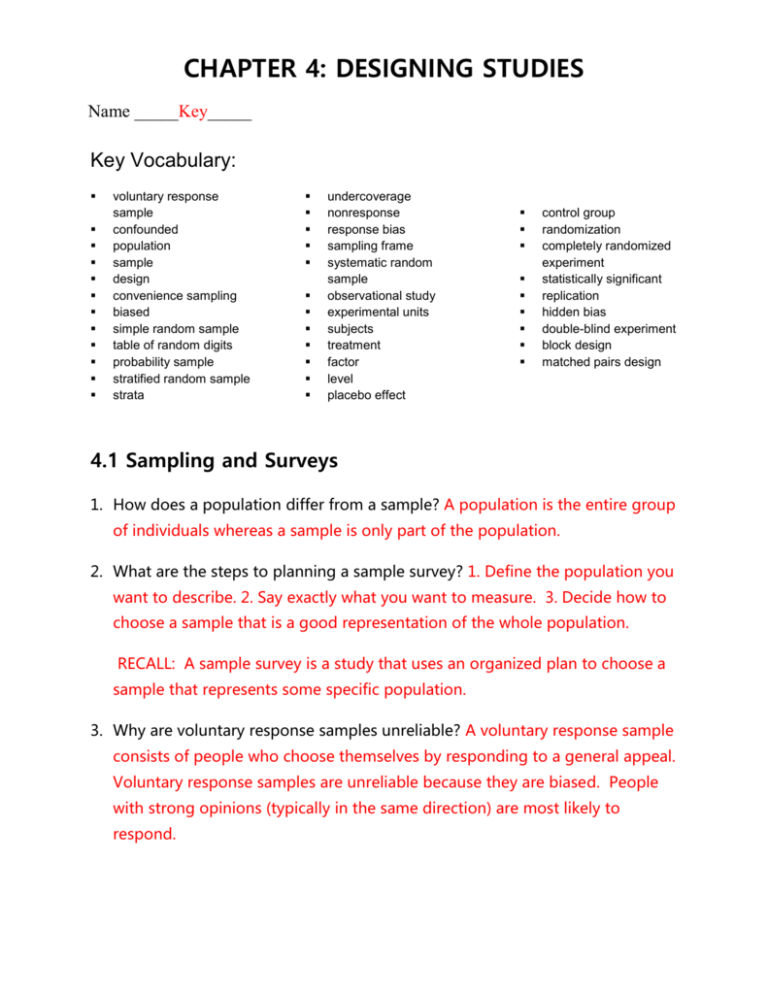

CHAPTER 4: DESIGNING STUDIES Name _____Key_____ Key Vocabulary: voluntary response sample confounded population sample design convenience sampling biased simple random sample table of random digits probability sample stratified random sample strata undercoverage nonresponse response bias sampling frame systematic random sample observational study experimental units subjects treatment factor level placebo effect control group randomization completely randomized experiment statistically significant replication hidden bias double-blind experiment block design matched pairs design 4.1 Sampling and Surveys 1. How does a population differ from a sample? A population is the entire group of individuals whereas a sample is only part of the population. 2. What are the steps to planning a sample survey? 1. Define the population you want to describe. 2. Say exactly what you want to measure. 3. Decide how to choose a sample that is a good representation of the whole population. RECALL: A sample survey is a study that uses an organized plan to choose a sample that represents some specific population. 3. Why are voluntary response samples unreliable? A voluntary response sample consists of people who choose themselves by responding to a general appeal. Voluntary response samples are unreliable because they are biased. People with strong opinions (typically in the same direction) are most likely to respond. CHAPTER 4: DESIGNING STUDIES 4. Why might convenience sampling be unreliable? Since convenience sampling involves choosing individuals who are easiest to reach, it often produces unrepresentative data; i.e. this method produces results that are not necessarily reliable. Furthermore, the results are typically biased. 5. What is a biased study? A statistical study that systematically favors certain outcomes; either overestimating or underestimating the outcome. 6. Define simple random sample. (SRS) A simple random sample of size n consists of n individuals from the population chosen in such a way that every set of n individuals has an equal chance to be the sample actually selected. 7. What two properties of a table of random digits make it a good choice for creating a simple random sample? (1). Each entry in the table is equally likely to be any of the 10 digits 0 – 9. (2). The entries are independent of each other; knowledge of one part of the table gives no information about any other part. 8. State the two steps in choosing an SRS? (Using Table D) Give each member of the population a numerical label of the same length. Read consecutive groups of digits of the appropriate length from Table D. Your sample contains the individuals whose labels you find. 9. How do you select a stratified random sample? First classify the population into groups of similar individuals called strata. Then choose a separate SRS in each stratum and combine these SRSs to form the full sample. Note: If the individuals in each stratum are less varied than the population as a whole, then a stratified random sample can produce better information about the population thatn an SRS of the same size. CHAPTER 4: DESIGNING STUDIES 10. What is cluster sampling? Cluster sampling involves dividing the population into smaller groups. Ideally, these clusters should mirror the characteristis of the population. Then choose a SRS of the clusters. All individuals in the chosen clusters are included in the sample. 11. What is the difference between a strata and cluster? Cluster samples are often used for practical reasons, as in the school survey example. They do not offer the statistical advantage of better information about the population that stratified random samples provide. This is because clusters are often chosen for ease or conveniences, so they may have as much variability as the population itself. In essence, strata should contain similar individuals with large differences between strata; whereas a cluster should look just like the population, just on a smaller scale. 12. Give an example of undercoverage in a sample. Undercoverage occurs when some groups in the population or left out of the process of choosing the sample. An example of undercoverage in a sample is collecting data for a high school study but neglecting to allow freshman students to participate. Textbook example: An opinion poll conducted by calling landline telephone numbers will miss households that have only cell phones as well as households without a phone. Page 221 13. Give an example of non-response bias in a sample. Non-response bias occurs when an individual chosen for the sample can’t be contacted or refuses to cooperate and/or participate. For example, retired people may be more likely to respond to a particular survey; thus giving their opinion(s) more weight. A poll about Social Security reform, with mostly senior citizen CHAPTER 4: DESIGNING STUDIES participants, could give a misleading impression of the actual views of the population. 14. What factors can cause response bias in a sample. Response bias involves giving an incorrect response. Factors causing response bias include: gender, race, age, perception, memory recall, philosophical views, etc. 15. How can the wording of questions cause bias in a sample? Confusing or leading questions can introduce strong bias. Changes in wording can greatly change a survey’s outcome. Even the order in which questions are asked matters. 16. What is the difference between nonresponse and voluntary response? The term “voluntary response” can be misused in an attempt to explain why certain individuals do not respond in a sample survey. Their idea is that participation in the survey is voluntary (optional) so anyone can refuse to take part. This is actually nonresponse. (Note: Nonresponse can only occur after a sample has been selected. In a voluntary response sample, every individual has opted to take part, so there won’t be any nonresponse. 4.2 Experiments 1. How does an experiment differ to an observational study? An observational study observes individuals and measures variables of interest but does not attempt to influence the responses. An experiment; however, deliberately imposes some treatment on individuals to measure their responses. An experiment is a statistical study in which a treatment is imposed upon people, animals, or objects (the experimental units) to observe the response. 2. What is a lurking variable? A variable that is not among the explanatory or response variables in a study but that may influence the response variable. CHAPTER 4: DESIGNING STUDIES 3. What is confounding? Confounding occurs when two variables are associated in such a way that their effects on a response variable cannot be distinguished from each other. In other words, it becomes difficult to determine which of two lurking variables is having the effect on the response variable. 4. Explain the difference between experimental units and subjects. The experimental units are the smallest collection of individuals to which treatments are applied. When the units are human beings, they often are called subjects. 5. Define treatment. A specific condition applied to the individuals in an experiment is called a treatment. 6. What is the difference between factor and level in an experiment? Example on page 235. A factor refers to the explanatory variables in an experiment. An experiment that studies the joint effects of several factors requires a treatment that is performed by combining a specific value called a level. 7. Explain how to perform a completely randomized design. Comparison alone isn’t enough to produce results we can trust. It is necessary to assign treatments at random (using some sort of chance process) to the experimental units. This is a completely randomized design. 8. What is the significance of using a control group? The primary purpose of a control group is to provide a baseline for comparing the effects of the other treatments. 9. The basic principles of statistical design of experiments are: Control for lurking variables that might affect the response: Use a comparative design and ensure that the only systematic difference between the groups is the treatment administered. CHAPTER 4: DESIGNING STUDIES Random assignment: Use impersonal chance to assign experimental units to treatments. This helps create roughly equivalent groups of experimental units by balancing the effects of lurking variables that aren’t controlled on the treatment groups. Replication: Use enough experimental units in each group so that any differences in the effects of the treatments can be distinguished from chance differences between the groups 10. Describe the placebo effect. It is the measured response to a dummy treatment. The strength of the placebo effect is a strong argument for randomized comparative experiments. A placebo (fake treatment), as used in research, is an inactive substance or procedure used as a control in an experiment. The placebo effect is the measurable, observable, or felt improvement in health not attributable to an actual treatment. In other words, patients get better because they expect the treatment to work even though they have received an inactive treatment. 11. Define randomization. Randomization is the process of assigning subjects or objects to a control or experimental group on a random basis. 12. Define statistically significant. Something is statistically significant when the observed effect is so large that it would rarely occur or be explained by chance. 13. Describe a block design. A block is a group of experimental units that are known before the experiment to be similar in some way that is expected to affect the response to the treatments. In a randomized block design, the random assignment of experimental units to treatments is carried out separately within each block. Blocks are another form of control. 14. When does randomization take place in a block design, and how does this differ to a completely randomized design? It occurs separately within each CHAPTER 4: DESIGNING STUDIES block. A randomized block design allows opportunity to form separate conclusions about each block. Blocking also allows more precise overall conclusions. It differs from a completely randomized design in the sense that it doesn’t assign treatment by chance to all experimental units. Blocking helps to reduce unwanted variability among experimental units. 15. What is the goal of a matched pairs design? Matched pairs are a common form of blocking for comparing just two treatments. In some matched pairs designs, each subject receives both treatments in a random order. In others, the subjects are matched in pairs as closely as possible, and each subject in a pair receives one of the treatments. 16. State the two most common ways in which matched pairs experiments are designed. Each subject receives both treatments in a random order. The subjects are matched in pairs as closely as possible, and each subject in a pair receives one of the treatments. 17. What are the advantages of a double-blind study? It removes bias factors. Neither the subjects nor those interacting with them and measuring their responses know who is receiving which treatment. 4.3 Using Studies Wisely 1. What are the criteria for establishing causation when we can’t experiment? Lack of realism can limit our ability to apply the conclusions of an experiment to the settings of greatest interest. To answer cause-and-effect questions, we simply need to perform a randomized comparative experiments. There are instances when we can’t. It’s difficult to randomly assign people to text while driving. Therefore, the best data we have to consider comes from observational studies. CHAPTER 4: DESIGNING STUDIES 2. What is meant by inference about cause and effect? A well-designed experiment that randomly assigns treatments to experimental units allows inference about cause and effect.