Scientific method and scientific variables

advertisement

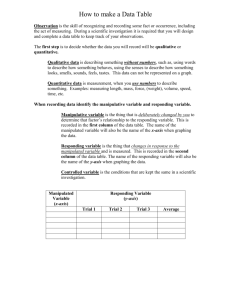

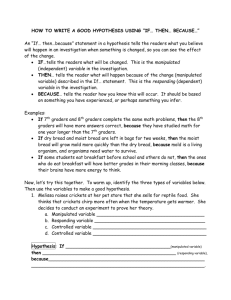

Science is a structured method for learning the rules of the universe. The method that is employed for making these discoveries is the Scientific Method, (which you have probably heard of) and which uses the following steps: (for our purposes the words “hypothesis” and “prediction” can be used interchangeably) Ask a question from a hypothesis test the hypothesis make a conclusion about the hypothesis Generally speaking, the “rules of the universe” take the form of relationships between variables. In science, the word variable refers to anything that can be observed and measured. (examples: time, volume, mass, voltage, speed, etc.) In most scientific investigations there are three basic types of variables: manipulated, responding, and controlled. The manipulated variable (also called the independent variable) is one that the investigator will make changes in. The manipulated variable is the one that the investigator is able to make decisions about ahead of time (Will it be increased, or decreased? Will it be changed a little, or a lot?) The responding variable (also called the dependent variable) is the one that responds to changes in the manipulated variable The goal of most scientific investigations is to find a relationship between the manipulated and responding variable. If other variables might also have an effect on the responding variable, then they must be kept from changing so that their influence is not confused with that of the manipulated variable. The Controlled variables are those which are intentionally prevented from changing so that they will not have an effect on the dependent variable. How to plan and conduct a scientific investigation: 1. Observe a phenomenon that grabs your interest (example: My father stored his batteries in the refrigerator — weird.) 2. Identify two variables (only two) that might be related to each other, and ask a question about the relationship between them. The best format for this question is: “Does changing the _______ have an effect on ________?” If you use this format, it is easy to determine which variable is your manipulated variable and which is your responding variable. Whichever variable you put in the first blank is your manipulated variable, and the one in the second blank is the responding variable. ( Does changing the temperature have an effect on the ability of a battery to hold a charge?) ↑ ↑ Manipulated variable Responding variable 3. Make a prediction about the relationship between the manipulated and responding variables. This prediction is also called the hypothesis. A good way to phrase your hypothesis is by using the “if, then, because” format, which takes the form of “If (the manipulated variable does this), then (the responding variable will do that), because (of a reasonable hunch I have).” (Example: If the temperature is kept low, then the batteries will hold their charge longer, because low temperatures prevent chemicals from breaking down.) 4. Plan out an experiment that will let you test your hypothesis. At this point you need to determine how you will measure your manipulated and responding variables. (Example: temperature (manipulated variable) will be measured in degrees Celsius of the environment in which the batteries are stored, and ability of the batteries to hold a charge (responding variable) will be measured in the number of minutes the batteries can power a toy car) In order to determine the relationship between the manipulated and responding variables, the manipulated variable must be changed! This is often done by having a control group that is “normal” (batteries stored at room temperature), and an experimental group that has been manipulated to show some type of change (batteries stored in a refrigerator). Also, you need to determine what controlled variables you will be necessary. Remember that when you control a variable, you keep it from changing. Any variable, other than the manipulated, that you think might cause changes in the responding variable must become a controlled variable and kept at a constant value throughout the experiment. If you do not control variables that you should have, then the validity of your experiment is called into question. The validity of an experiment is the degree to which others will believe your results to be true. Without validity, an experiment is just a waste of time and money. (Example: brand of battery, size of battery, age of battery, and the toy car would all have to be kept the same in order to protect the validity of this experiment; therefore these would all be controlled variables) 5. Make a list of the materials you will need. 6. Write out the procedure (all the crucial steps needed to conduct the experiment) in a logical order. The procedure must be written in such a way that a person could read it and reproduce the experiment exactly as you performed it. 7. Conduct the experiment and record your data on a data table. The data table should always be divided into two columns, one for the manipulated variable, and one for the responding variable. Temperature ( °C) Ability to hold charge (minutes) Example: 8 °C 25 min 20 °C 18 min It is extremely important to repeat the procedure several times in order to ensure consistency in the results, otherwise your data will lack validity. (Ex: repeat with a greater number of batteries, repeat over a number of different temperatures) 8. Analyze the data and make a conclusion about your hypothesis. The conclusion should always refer back to the data and indicate whether the data supports the hypothesis or not. (Ex: The data supports the hypothesis, because the batteries stored at 8 °C lasted 7 minutes longer than the ones stored at 20 °C) 9. After reaching your conclusion it is always important to suggest ways in which the experiment could be improved. (Ex: store batteries for a longer period of time, use more batteries, use a more reliable testing mechanism, etc.) Never, never, never say : “human error”