UNRT_C4D Girls` Leadership_Draft_11 Nov 2011

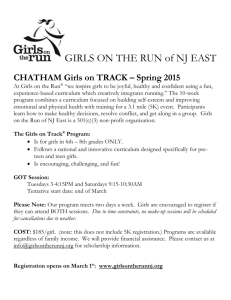

advertisement