PlasmaTech 1 gas flo..

advertisement

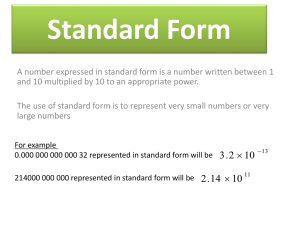

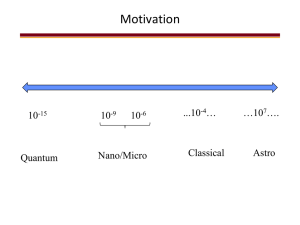

Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 Lecture 1: Basic gas Properties – Fluid Dynamics As gas atoms/molecules (or particles) move through out a volume they collide and randomly distribute their energy. A basic tenant of statistics is that random processes result in Normally distributed results. This is know as the central limit theorem, see for example Box Hunter and Hunter, “Statistics for experimenters” (Yu Lei has the book right now so I don’t have the title quite right.) The normal distribution is y 2 py const exp . 2 2 Here is the population variance, is the population standard deviation, and is the central value. The distribution looks like 1 1.2 1 0.8 p(y) Normal Distribution 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 y 1 2 3 4 5 Concept of Temperature Maxwell and Boltzman proposed that this same distribution can be used to model the velocity distribution of particles in thermal equilibrium. (This is known as the Maxwell Distribution, Boltzman Distribution and the Maxwell-Boltzman Distribution.) Using this assumption we have that the velocity distribution is mv 2 f v const exp , 2kT Page 1 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 while the energy distribution is . f const exp kT Here k is Boltzman’s constant and T is the temperature. Notice that the temperature is simply a measure of the random energy of the system. NOTE that often ‘kT’ is simply written as ‘T’ and hence ‘T’ is given units of energy. Problem 1 Show that if in one dimension f v dv n then 1/ 2 m . const n 2kT Also show that if in three dimensions 3 f v dv n then 3/ 2 m . const n 2kT Here n is the particle density. Typically, the velocity distributions are well behaved and we have distributions as such: The Maxwellian Distribution Page 2 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 1.2 1 0.8 f(v) Maxwellian 0.6 0.4 2Vth 0.2 0 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 V/Vth Where 1 2 3 4 5 mv 2 m 1/ 2 f v n exp . 2kT 2kT This is what happens if there are enough collisions to evenly distribute the energy. In other cases, however, we will be working in with a system in which the rate of collisions is not large enough to evenly distribute the energy. Some typical examples are: The bi-Maxwellian Distribution Page 3 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 1.2 1 0.8 f(v) Bi-Maxwellian 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 V Where m mv 2 f v 1 n exp 2kT1 2kT1 . 1/ 2 2 m m v n exp 2kT2 2kT2 1/ 2 The drifting Maxwellian Distribution Page 4 1 2 3 4 5 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 1.2 1 0.8 f(v) Drifting Maxwellian 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 V Where 1/ 2 mv v0 m f v n exp 2kT 2kT 2 . and the ‘bump-on-tail’ Page 5 1 2 3 4 5 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 1 0.9 0.8 0.7 0.6 f(v) Bump-on-tail 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 -5 -4 -3 -2 -1 0 V 1 2 3 4 5 Where f v fMaxwel l f drift . While other distributions are certainly possible, these four comprise most of what is observed in laboratory plasmas. Normalization of the velocity distribution. The velocity distribution is normalized so that if all particles of all velocities are accounted for then one has the local particle density. This means that f vdv n . Thus in one dimension mv 2 m 1/ 2 f v n exp or in three-dimensions 2kT 2kT mv2 m 3/ 2 f v n exp 2kT 2kT Concept of Thermal Velocity We know that m 1/ 2 mv 2 f v n exp 2kT . 2kT The central part of the distribution, ± sigma, will have ~69% of all the particles at or below a given v. This velocity is known as the thermal velocity, vth. Thus we can ‘derive’ 1/ 2 v v0 2 m f v n exp 2 2kT 2vth Page 6 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 thus vth2 kT . m Note that in some texts vth2 2kT . We will not use this definition. m Average velocity v vf vdv f v dv 1 vf v dv n v 2 1 m 1/ 2 n v exp dv n 2kT odd function 2vth2 even function 0 (Odd functions int egrated from to is zero.) This is very different than the average speed, which is v 1 v f vdv n 1/ 2 m 2kT v 2 v exp 2 dv 2vth v 2 1 1 1/2 2 0 vexp 2 dv vth 2 2vth v2 v 1 1/2 v vth 2 0 exp 2 d 2 vth 2v th vth 1 u 2 u 2 vth 2 0 exp d 2 2 2 1/2 1/2 1 vth 2 expy dy 2 0 1/ 2 2kT m in one-dimension. In three-dimension the average speed is 1 v v f v4v2 dv n 8kT1/ 2 m Page 7 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 Average energy in one-dimension E 1 1 m v 2 v 2 f vdv 2 n v 2 1 m 1/ 2 2 m v exp 2 dv 2 2kT 2vth v 2 1 1 1/ 2 2 m 2 v exp 2 dv 2vth 2 2v th 2 1/2 v v 2 v exp vth 2vth2 d vth 1/2 y 2 2 y exp dy 2 1 kT 8 1 kT 8 1/2 1 y 2 y 2 y exp exp kT dy 8 2 2 1/2 1 kT 8 2 kT2 1/2 In three dimensions the average energy is 3kT E . The derivation of this is left homework. 2 Concept of Mean-free path As atoms/molecules pass through a volume, they collide with other atoms/molecules. A prime example of this is Brownian motion – the motion of a dust particle in air that moves in disjointed fashion. also kno wna s a random walk We can calculate the mean-free path, mfp, if we consider the following picture. Page 8 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 If we were to repeatedly fire test particles at the target, a fraction of the test particles will be scattered by collisions with atoms in the target. The fraction scattered is simply the area ratio. N Fraction scattered A where N is the number of atoms in the target. Assuming that our target is a part of a larger piece of material, in which we know the density, n, of the material then Fraction scattered nAdx ndx . A Now let us send a continuous flux, , of test particle – or a current density J, at the target then the change in J across the target is J Jafter Jbefore 1 ndx J before Jbefore Jndx or Page 9 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 dJ Jn dx J J 0 expx / mf p 1 where mf p . n We can make approximations of the cross section of the target atom, based on the radius of the target atom. This is known as the hard-sphere approximation, which is at best imprecise. The reality is that the interaction, and hence collisions, is related to the target atom electron orbitals and particle energies, i.e. it is quantum mechanical in nature. From our above discussion, we can calculate the Mean frequency of collisions v vn mf p And the mean period of collisions 1 Of course the average collision frequency for a distribution of velocities is n v noting v . Gas pressure Lets assume that we have a particle in a box of sides l . Assume that the particle is reflected with M mvx mvx init ial momentum fi nal momentum no loss of energy (why?) when it hits wall A1. Thus E 0 but 2mvx Where we have assumed that v y 0 v z . Now let us assume that the particle travels across the 2l volume without striking anything else and reflects off side A2. The round trip time is t vx The force applied to side A1 is M 2mvx mvx2 F t 2l vx l and the pressure is F mv 2 P 2 3x l l Putting in more particles we find Page 10 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 P all mv2x N m 3 3 l part icles l all mv 2x part icles N mn v 2x 1 2n n v 2x 2n Ex 2 nkT the ideal gas law! Lecture 2 Gas Flow Conservation of Flux, which we will prove later If a gas passes through a series of pipes with various cross sectional areas, then the flux is conserved. Physically this should be obvious. Think of this as the same as saying that we do not have rarefaction/compression of the gas, nor do we have a source/sink for the gas. 1 2 3 P2 P1 P3 P4 A1 A1 n1 v1 A2 n2 v2 A3 n3 v3 ... Flow resistance/conductance If a gas flow through a pipe, we expect some pressure differential to cause the flow. The ratio of the pressure to the flow is known as the resistance, R. P R . The conductance is simply the inverse of the R, 1 # /s / area C R P Force / area These equations are very similar to the resistance in a circuit, where we replace voltage with pressure. Thus for a series of pipes Page 11 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 Ptotal but Ctotal Ptotal Pi and so i Ptotal 1 Ctotal i Ci i Ci 1 1 Ctotal i Ci or in a similar vane, Rtotal Ri . i For Parallel pipes we find Ctotal Ci and i 1 1 Rtotal i Ri Pumps We can think of pumps as simply another conductance, S. After all we are trying to have a certain go through the pump and the pump acts as if the back side has a pressure of zero. Here however, the pump conductance is given a special name, S, for ‘speed’. If a pump has a pipe connecting it to the chamber, we get an effective pump speed from 1 1 1 Seff S Cpipe Example: Given a pipe with a conductance C= 100 L/s and a pump speed of S = 200 L/s we find that the effective pump speed is 66.6 L/s. This means that we using only 33% of our possible pumping ability. This can become critical in the design of a process system. Types of gas flow. There are three radically different types of gas flow. They are: Laminar fluid (viscous) flow Turbulent fluid flow Molecular flow Page 12 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 The distinction between Laminar (‘layer’) and turbulent is often seen in wind tunnel experiments on new cars. Lamin ar flow Turbulent flow One can determine if one is operating in fluid flow or molecular flow by determining the Knudsen number, Kn. mean free path for all colli sions Kn mf p d charact eristic distan ce across system 1 Molecular ~ 1 Transition Fluid 1 We can calculate the conductance in molecular and fluid flow regimes from the following equations. (Note these equations are at least partly experimental approximations.) Fluid Flow through a round tube P1 d P2 L with the requirements P1 > P2 and L >> d. Laminar Flow (the most common for us) d 4 P1 P2 C ; gas viscosity 128 L 2 Here P1 and P2 are in mbar and L and d are in cm, giving C in L/s. Turbulent Flow 3/ 7 gas cons tan t 1/ 7 2 2 2 4 /7 d 4 5 3 P1 P2 R C d T P1 P2 3.2 4 2L M molar Molar mass Here, Mmolar is in g/mole, R is 83.14 mBar L/Mole/K and T is in K. Fluid Flow through an orifice Page 13 Class notes for EE6318/Phys 6383 – Spring 2001 This document is for instructional use only and may not be copied or distributed outside of EE6318/Phys 6383 P1 P2 D d with the requirements P1 > P2. 1/ 2 1/ (1 )/ P1 d 2 2RT P2 P2 C 1 P1 P2 4 Mmolar P1 1 P1 C where P is the adiabatic cons tan t CV 1/ 2 Molecular flow through a round tube 1/ 2 RT d 2 2Mmolar C ; where 1 1.12 is a fudge factor 4 1 3 L 4 d Page 14