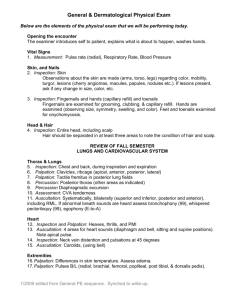

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

advertisement

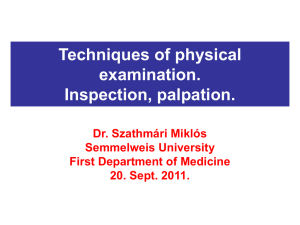

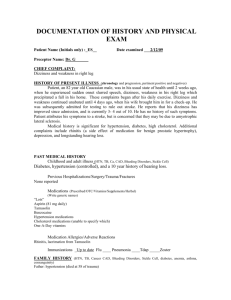

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION Basic methods of Examination A systematic approach to the bedside examination of a patient is essential to determine the significance of an abnormal physical finding. It includes five basic methods-namely, inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation, and olfactory examination. Inspection Inspection is seeking physical signs by observing the patient. Of the several methods of examination inspection is the least mechanical the hardest to learn, but it yields most physical signs. More diagnoses are probably made by inspection than by all other methods combined. The method is the most difficult to learn because no systematic approach can encompass the variety of signs. More than any other method, inspection depends entirely upon the knowledge of the observer; we tend to see things that have meaning for us. The layman looks at a person and concludes that there is something “peculiar” about him; the physician gives a glance and diagnoses acromegaly. From his study of disease, he can dissect the “peculiarity” and recognize the diagnostic components, such as the enlarged supraorbital ridges, the widely spaced teeth the macroglassia, the buffalo hump, the huge hands and feet. Practice is required to learn inspection. 1. General inspection. The initial act of physical examination is the inspection of the body as a whole. Most clinicians believe that composite pictures of disease, although composed of many sighs, strike them at a glance; they attempt to teach others perceive likewise. In looking at the patient as a whole, many facts are noted methods in physical examination/inspection. General inspection about motor activity, body builds, outstanding anatomic malformation, behavior, speech, nutrition, and appearance of illness. 2. Local inspection. Focusing observation on a single anatomic region yields hundreds of physical signs. Since only signs perceived by inspection can be illustrated, the myriad of pictures used in books on surgical diagnosis hint the importance of the method in that field. The dermatologist relies almost entirely on the appearance of skin lesions to make a diagnosis. 3. Usage more or less confines the term inspection to observation with the unaided eyes. Actually, visual, visual signs are the chief or only rewards in the use of the ophthalmoscope, slit lamp, gonioscope, otoscope nasoscope, laryngoscope, bronchoscope, gastrocope, thoracoscope, peritoneoscope, cystoscope, anoscope, and sigmoidoscope. The pathologist uses the microscope; the radiologist inspects the fluoroscopic screen and photographic films. Palpation The usual definition of palpation is the act of feeling by the sense of touch. But this is too limited; when the physician lays his lands upon the patient, he perceives physical signs by his tactile sense, temperature sense, and his kinesthetic sense of position and vibration. Palpation is widely used in the physical examination especially in the abdomen examination. 1. Sensitive parts of the Hand: Tactile sense. The tips of the fingers are the most sensitive for fine tactile discrimination, and temperature sense. Use the dorsa of the hands or fingers; the skin is much thinner than elsewhere on the hand. Vibratory sense. Palpate with the palmar aspects of the metacarpophalangeal joints rather than with the finger tips to perceive vibrations such as thrills or the precordial cardiac thrust. Probe the superiority for yourself by touching first the fingertip, then the palmar base of your finger, with a vibrating tuning fork. Sense diagnostic Mode: Symptoms and signs. Use the grasping fingers, so you perceive with sensations from your joints and muscles. 2. Structures Examined by palpation. Palpation is employed on every part of the body accessible to the examining fingers: all external structures, all structures accessible through the body orifices, the bones, the joints, the muscles, the tendon sheaths, the ligaments, the superficial arteries, thrombosed or thickened veins, superficial nevers, salivary ducts, spermatic cord, solid abdominal viscera, solid contents of hollow ivccera, accumulations of body fluids, pus, or blood. 3. Quality Elicited by palpation: Texture. The skin and hair, Moisture. The skin and mucosa. Skin temperature. At various levels of the body. Masses. The size, shape, consistency, mobility, pulsation (expansile or transmitted) precordial cardiac thrust. Crepitus. In bones, joints, tendon sheaths, pleura, subcutaneous tissue. Tenderness. In all accessible tissues. Thrills, over the heart and blood vessels. Vocal fremitus. 4. Special Methods of palpation: Light palpation. Deep palpation. Ballottement. Fluctuation. Fluid wave. Percussion In physical diagnosis, percussion is the method of examination in which the surface of the body is struck to emit sounds that vary in quality according to the underlying tissues. Methods of percussion: Immediate or indirect percussion. In the method the left middle finger is laid upon the body surface to serve as a pleximeter; it is struck sharp blow with the tip of the right middle finger, the plexor immediate or direct. The body surface is struck directly with one or more fingers of a hand. 1. Sonorous percussion. This term is applied to any method of percussion when its purpose is to ascertain the density of the tissue by the sound emitted when struck. Various densities emit sounds given special meanings. The percussion notes may be arranged in sequence according to the density that produces them, from least to most dense: tympany hyperresonance, resonance, impaired resonance, dullness, flatness. Certain steps in normal tissues. Tympany is the sound emitted by percussing the air-filled stomach; resonance is produced by striking the air-filled lungs; flatness results from the thigh. In general the pitch or frequency of the sounds progresses through the series from lowest for tympany to highest for flatness; the duration of the sound ranges in the series from long to short. Sonorous percussion is employed to ascertain the density of the lungs, the pleural space, the pleural layers, and the hollow viscera of the abdomen. 2. Definitive percussion, where two structures in apposition have greatly contrasting densities, as demonstrated by their percussion notes, mapping of area of greater density furnishes a concept of the size of the structure or the extent of its border. Any method of percussion used for this purpose is termed definitive percussion. Definitive percussion is commonly employed to ascertain the location of the lung bases, the width of the lung apices, the height of fluid in the pleural cavity the width of the mediastimum, the size of the heart, the outline of dense masses in the lungs the size and shape of the liver and spleen, the size of a distended gallbladder and urinary bladder, the level of ascitic fluid. Auscultation Although auscultation might literally imply the act of hearing to obtain physical signs, usage restricts it almost solely to hearing through the stethoscope. Rales and friction rubs. Crepitus can be heard in joints tendon sheaths, muscles, fractured bones, and in subcutaneous emphysema. The heart makes its various valve sounds with their splitting, murmurs, rhythm disturbances, pericardial rubs and knocks. Auscultation of the abdomen reveals bowel sounds, murmurs from aneurysms and stenotic arteries, especially the renal. The stethoscope is applied to the scrotum to detect bowel sounds in a scrotal hernia. As every musician knows, the ear can be trained to recognize sounds more accurately. Each person learns to recognize the voices of many associates by patterns of pitch and overtones. Olfactory examination In olfactory examination physician makes use of his sense of smell to obtain the abnormal odors of the patients and identify the signs of diseases. General Inspection General inspection is a series of accurate and meaningful observations. It includes a general survey of the patient’s sex, age, mental status, mood, posture, body movements, gait speech, breath odor, state of nutrition, stature, temperature and skin. General inspection begins with history taking. General appearance Even before the formal physical you will begin making observations that may alert you to disease. Throughout the history and physical, these cumulative observations form the basis for logical diagnostic deductions. As the patient moves into the examining room, you might note the gait. Is it painful? Is there evident favoring of one side of the body, as in stroke? A wealth of information can be gained by shaking hands with the patient. Warm, moist hands may suggest hyperthyroidism. When the patient speaks, does the tone of his voice suggest the hoarseness of laryngeal cancer, the weakened, thickened, and lowered voice of hypothyroidism; the “vocal ataxia” or “scanning speech” of multiple sclerosis or cerebellar disease? The face has always been the mirror or the mind. It shows pain, fear, anxiety, and sadness. It is in the face that we first notice whether our patients are pale, ruddy, cyanotic, or icteric. Thickened features suggest hormonal imbalance-e.g., of the thyroid or growth hormone. Fullness may be a consequence of edema, obesity, or a result of excess corticosteroids. A malar flush may signal lupus or mitral stenosis. Shiny skin and tight features first alert us to possible scleroderma. Cranial nerve dysfunction may be manifested by ptosis, strabismus, or facial asymmetry. Habitus refers to your patient’s general shape-his or her body build. Cachexia is an extreme thinness and debility caused by some serious disease, such as cancer or chronic infection. Signs of recent weight loss, such as loose clothes, newly punched belt holes, and redundant skin folds, clue the clinician to a loss of flesh or fat that may or may not have been noticed by the patient. Simple obesity is a deposition of body fat in excess of some arbitrary standard. Pathologic obesity is deposition of body fat to the point of physiologic compromise of the individual, who may have respiratory, cardiac, or orthopedic difficulty. In these conditions excess fat is apportioned generally around the body-face, trunk, buttocks, and extremities. Deposition of fat around the trunk, with thin extremities in which muscle wasting is evident, may suggest hypercorticosteroidism. Vital Signs Because a heartbeat, breathing, and body warmth are the clinical signs of life (the absence of which signaled death in the era before the advent of modern laboratory aids such as the electroencephalogram), the so-called vital signs (pulse, respiratory rate, temperature, and blood pressure) continue to be the most frequently examined of all physical findings. Temperature The temperature is generally taken by placing the thermometer under the patient’s tongue for 3 minutes. The temperature may be taken orally or rectally, and in the United States the Fahrenheit scale is usually used. Falsely low levels may result from incomplete closure of the mouth, breathing through the mouth, leaving the thermometer in place for too short a time, or the recent ingestion of cold substances. Falsely elevated levels may result from inadequate shaking down of the thermometer, previous ingestion of warm substances, smoking, recent strenuous activity, or even a very warm bath. In most persons there is a diurnal (occurring every day) variation in body temperature of 0.3~1C. The lowest ebb is reached during sleep, at which time the temperature may fall as low as 35.7~36.1C. As the patient begins to awaken, the temperature slowly rises. You will note that the upper limit of normal on the standard thermometer is 37C. Rectal temperatures are usually 0.3 to 0.5C higher than oral temperatures, but they tend to be less subject to alteration by the oral factors mentioned above and are generally more constant and reproducible. Pulse The radial pulse is best taken at the base of the patient’s thumb. If the examiner uses two of three fingers along the course of the artery, he or she may determine the pulse contour as well as the rate. Initially, and always if the pulse is irregular, the examiner should count the pulse for a full 60 seconds. If the pulse rate is between 60 and 100, and the rhythm is absolutely regular, many physicians will “shortcut” and count the pulse for 30 seconds, then multiply by two. If the radial pulse is poor or irregular, the pulse may be taken by listening to or palpating the apex of the heart (the apical pulse). The normal resting pulse rate ranges from 60 to 100. It may b in the 50 in a conditioned athlete, or 100 or over in an excited patient. Rates less than 60 are often referred to as bradycardia, and rates over 100 as tachycardia. The pulse rate and rhythm should be recorded, and if abnormal contour is discovered, that too must be noted. Respirations Many physicians find it of value to count the respirations while appearing to take the pulse, since the natural tendency of the patient is to breathe awkwardly under observation. Normal respiratory rate is between 8 and 14 per minute in adults and is somewhat more rapid in children. Note abnormalities of respiratory rate and rhythm. Extremely slow respiration usually indicates central nervous system respiratory depression due to disease or drugs. Periodic or Cheyne-Stokes respiration occurs with serious cardiopulmonary or cerebral disorders. Deep slow breathing (Kussmaul’s respiration) characterizes acidosis, a state in which the physiologic response to increased metabolic acid in the blood is a compensatory “blowing off” of carbon dioxide. Extreme tachypnea is present during many acute illnesses. It may be due to chronic or acute pulmonary or cardiac disease or systemic disorders, such as shock, severe pain, and acidosis; although it may represent undue excitement or nervousness, especially when accompanied with sighing, an organic cause should be excluded. The patient’s preferred position is important. Can he lie flat comfortable? Patients with congestive heart failure prefer the sitting position, as do patients with pulmonary disease during acute attacks of infection or bronchospasm. Patients with pericarditis often sit and lean forward. Blood pressure The normal adult blood pressure varies over a wide range. The normal systolic range varies from 95 to 140 mm Hg, generally increasing with age. The normal diastolic range is from 60 to 90 mm Hg. Pulse pressure is the difference between the systolic and diastolic pressure. Mean pressure can be approximated by dividing the pulse pressure by three and adding the value to the diastolic pressure. Routing measurements should be made with the patient sitting and recumbent. Skin The skin has been called the “mirror” of an individual’s health, since diseases of any organ system is often reflected from it. Inspection is the most important part of the examination of the skin. Color, shape, skin eruption, muculae, roseolae papulaes wheals, maculopqpulaes wheals, maculopapulaes spider angioma, petechia, purpura, ecchymosis, hematoma are noted. Obviously, skin color varies greatly from person to person and even from area to area on the same person. If possible by use of photographs or findings from earlier examinations, the previous skin pigmentation should be ascertained so that the present coloring can be evaluated more precisely. Usually, an area of increased or decreased pigmentation in skin that is otherwise normally pigmented signifies some abnormality-for example, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation or vitiligo. The normally occurring skin pigments are melanin, hemoglobin, and carotenoids. Diffuse or localized melanin hyperpigmentation can be seen in such conditions as Addison’s hypoadrenocorticism, hyperthyroidism, pregnancy, hemochromatosis, and, most commonly, after exposure to sunlight. Melanin pigment is lacking in albinism (diffuse) and vitiligo (patchy). Erythema of the skin results from increased amounts of oxygenated blood in the dermal vasculature, such as might occur with fever or sunburn. Increases in deoxygenated blood hemoglobin result in a bluish tint to the skin (cyanosis) in such conditions as congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and congenital heart disease with right-to-left shunts. Localized red or purple changes result from vascular neoplasms, birthmarks, and hemorrhage into the skin (petechiae and ecchymoses). Pallor results if the hemoglobin content of the skin is decreased, as in anemia or shock. Changes in the color of the skin may result from the deposition of pigments normally not found in significant quantities in the skin. Thus, the yellow or even greenish hue of jaundice results from increases in tissue bilirubin in the skin and sclerae. Carotenemia also results in yellowing or the skin but, unlike jaundice, the sclerae are not involved. This pigment change is caused by increased amounts of carotenoids in the skin and results from myxedema, diabetes, or ingestion of excess amounts of foods containing these pigments, principally carrots. Carotenemia is occasionally present during pregnancy. Certain metal salts, such as silver, gold, and bismuth, when administered over prolonged periods as mediacations, may be deposited in the skin and cause a greyish discoloration. Foreign bodies such as carbon-containing particles can also cause localized pigmentation of the skin-for example, tattoos. Generally, palpation of the skin is used to confirm and amplify the findings observed on inspection. Inspection and palpation are inseparable interrelated and the examiner often uses them synchronously. Such findings as temperature, moisture, texture, elasticity, and presence of edema in the skin are detected by palpation. Although the skin temperature is a poor gauge of the temperature of the inner body care, it may reflect a maladjustment in the thermoregulatory mechanism of the body. Thus, if a febrile person’s skin is warm and dry, one knows that sweat evaporation is not cooling the body and that the patient’s temperature is probably rising. On the other hand, if the skin is warm and wet, then the sweating is probably acting to reduce the temperature. Skin temperature depends on the amount of blood circulating through the dermis. Thus, localized hyperthermia indicates localized increased blood flow, as noted in localized burn or furuncle. Generalized skin hyperthermia suggests increased blood flow in the entire integument-for example, generalized sunburn and hyperthyroidism. Localized reduced blood flow results in coolness of that area-for example, peripheral arteriosclerosis and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Generalized cutaneous hypothermia signifies a generalized reduction of skin blood flow-for example, shock. Sweating results from autonomic discharge arising from stimulation of either the central nervous system or the peripheral nervous system. Various combinations of skin moisture and temperature findings can be evaluated on the basis of the previously described physiologic principles. Thus, cool wet hands in indicate vasoconstriction and adrenergic sweating-a combination often resulting from autonomic nervous system stimulation caused by anxiety. “Skin texture” refers to the quality and character of its surface. Is it rough and dry as it may become in hypothyroidism, the postmenopausal state, or “winter itch?” Is it velvety smooth, as seen in hyperthyroidism? Loss of elasticity of the skin refers to its inability to return promptly to its normal position when stretched or pulled. This occurs most commonly in such areas of chronic actinic damage as the backs of the hands and the face. Increased elasticity of the skin and joints occurs in the Ehler-Danlos syndrome (cutis hyperelastica). Laxness or laxity of the skin refers to sagging or looseness of the integument and is seen following rapid weight loss and in the aged as the result of a lifetime of gravitational pull on the loose tissues of the face, buttocks, and other areas of the body. Since the skin is a large depot for body water and electrolytes, much can be learned about the state of total body hydration by careful palpation. Thus, if the skin is loose, wrinkled, and lax in areas not previously subjected to chronic sun-damage, this suggests dehydration of the entire body. On the other hand, excess body water may also be stored in the skin and may be manifested by pitting edema, wherein firm pressure against the fluid-filled area results in an indentation in the skin. Edema Generalized edema is easily detected during inspection and usually results from nephrotic syndrome and sepsis and rarely from severe heart failure. Dependent edema involving the inferior extremities, on the other hand, is a consequence of systemic venous hypertension associated with right heart failure and can be detected by inspection. Hair Normal hair distribution is well appreciated by most examiners and need not be considered here. However, it should be remembered that facial, axillary, and public hair depend on the presence of sex and other hormones and thus is related to both the sex and the age of the patient. Scalp hair should be specifically examined for length, texture, fragility, sheen, and the ease with which hairs can be manually removed from their follicles. Lymph node Lymph nodes are distributed throughout the body but for most purposes can be divided into five major groups: cervicofacial-supraclavicular, axillary, epitrochlear, inguinal, and femoral. Other lymph node groups that occasionally become pathologically enlarged are the suboccipital, postauricular, suprasternal, and popliteal. Evaluation of the numerous lymph nodes of the mediastinum, abdomen, plevis, lymph nodes of the mediastinum, abdomen, pelvis, and lower extremities must be done by computed tomography (CT) or lymphangiography. Lymph nodes are examined by palpation. In general the tips of the first four fingers are sued, and five major qualities of the nodes are noted: location, size in centimeters (using a ruler), degree of tenderness, fixation to underlying tissue, and texture (hard, soft, etc.). Normal lymph nodes are not palpable. However, mild enlargement (<1 cm) of the inguinal nodes is quite common, and probably results from repeated superficial infections of the fee and legs. These nodes are soft, nontender, and movable, with normal overlying skin. Femoral node enlargement, in contrast, is more likely to be of clinical significance. Similar small, soft, movable nodes are also found in children in the cervicofacial and axillary areas as a result of exposure to upper respiratory pathogens and superficial infections of the upper extremities. Lymphadenopathy may be either localized or generalized. The former is generally associated with a local infectious process in the anatomic area drained by the nodes in question, or neoplasm. Texture, size, tenderness, and fixation can all weigh in favor of one or the other of these possibilities; hard nodes favor neoplsms, as do greatly enlarged (>3 cm), nontender, and fixed nodes. Small, soft, tender, red, and movable nodes are more often a result of inflammation or some other type of antigenic challenge. Location is also of importance; isolated occipital, postauricular, or epitrochlear lymphadenopathy is unusual in primary lymphoma and more commonly results from locallized inflammation. Posterior or anterior cervical, supraclavicular, mediastinal, or intraabdominal adenopathy is more commonly associated with neoplasia. Posture The patient’s position or posture may reveal significant information. (for example: arthritis, congestive heart failure, carcinoma of the body or tail of pancreance) thus, the position of the patient at the time of examination may suggest certain disease possibilities. Body movements Body movements are classified as voluntary and involuntary. Involuntary movements are usually abnormal and may occur in either conscious or comatose states. 1. The tics: These are habit spasms and usually involve the muscule of the eyes, face neck. They generally occur in tense or emotional persons. 2. Convulsive movements Convulsive movements are a series of violent involuntary muscule contractions. (1) Tonic convulsions are custained contractions. (2) Clonic ones are characterized by intermittent contraction and relaxation. (3) Tremors are trembling movements that are result of various causes such as fatigue, alcoholic intoxicaton. Certain drugs, thyroxicosis, parkingsonism, hysteria and nervous. (4) A flapping tremor can frequently be seen in the presence of hepatic cama. This is best seen in the hands, although it may occur in the feet or tongue, with the arms outstretched on the bed, the wrists dorsiflexed and the fingers spread apart, there occurs episodes of rapid alternating flexion and extension movements at the patient’s wrists and the metacarpophalangeal joints. Gait Abnormalities of gait are also noted during inspection. Neurologic deficits resulting from cardioembolic strokes or hypertensive cerebrovascular disease may be associated with abnormalities of gait. A parkinsonian gait may indicate Shy-Drager’s syndrome, which may be associated with orthostatic hypotension. Certain metabolic disorders such as hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, Cushing’s syndrome, and acromegaly can be suspected during inspection, and these metabllic diseases may be associated with various cardiovascular abnormalities including systemic and pulmonary hypertension and myocardial and pericardial diseases. Speech The character of a patient’s voice and the manner of his speech may be of considerable diagnostic aid, involvement of larynx by inflammation. TB or malignancy may result in hoarseness. In cerebral vascular accidents, the speech is often thick, and words are enunciated with considerable difficulty. In paralysis of recurrent laryngeal nerve the voice is weak and loss its normal resonating quality. Three different basic speech defects are encounteaed: pphonia, aphasia, and anarthria. Breath odors Nutrition As part of every P. E. the physician should record the patient’s sex, age, weight, height, temperature, pulse and respiratory rate. 1. Overweight or obesity may be either exogenous or endogenous in origin. Edema must be differentiated from obesity, in edema the tissues pit (indent) when pressed with finger. This phenomena is not present in obesity. 2. Underweight. The examiner should evaluate the patient’s present weight in term of his average weight; that is , has patient always been slender or has been lost weight, pepople may lost weight as the result of voluntarily decreased calaric intake or because of various wasting diseases, such as pulmonary TB, malignancy and hyperthyroidism. Stature “Stature” here refers to height and build. People’s height is below normal. Gigantism is of two essential types, both of which are caused by hypersecretion of the anterior pituitary growth hormone. This overactivity of anterior lobe gegins before the body epiphyses fuse, there results an individual of abnormally large stature with absent or retarted sexual development. On the other hand, the anteriar lobe becomes overactive following fuse of epiphyses, acromegaly results.