DYSPAREUNIA

advertisement

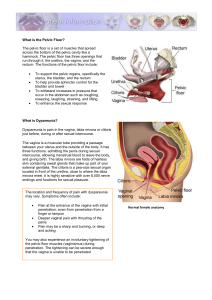

DYSPAREUNIA Professor Chris Sutton Professor of Gynaecological Surgery, University of Surrey, Guildford. UK The treatment of dyspareunia depends on the cause of the condition and apart from psychological causes, inducing vaginismus, the differential diagnosis includes inadequate lubrication, atrophy and vulvodynia (vulvar vestibulitis). The latter is a complex condition and although it is tempting to treat it by a laser skinning vulvectomy the problem usually occurs and has deep rooted psychological factors, sometimes requiring antidepressants and is exceedingly difficult to treat. Other causes, such as urethral disorders, cystitis and interstitial cystitis can also cause painful intercourse and are usually within the provenance of the urologists. Certain causes of superficial dyspareunia, such as imperforate hymen, hymenal tags or ridges at the posterior fourchette are amenable to carbon dioxide laser treatment directed via a colposcope using a moistened cotton wool ball as a back stop. The lasered area is usually left open to heal by primary intention and as with most laser craters there is very little in the way of stricture formation and fibrosis and the end result is usually a very neat healed area that is almost identical to the surrounding tissue. Causes of deep dyspareunia include endometriosis, pelvic congestion, adhesions or infections and adnexal pathology. The diagnosis usually requires laparoscopy and other ancillary investigations, such as transvaginal or transrectal ultrasound and many of these conditions can be treated by laparoscopic surgery. Endometriosis and pelvic venous congestion In his excellent monograph on endometriosis, Dan O’Connor reported on 717 patients that he had treated in his private practice and of these 668 were, or had been sexually active and 188 (28%) of these women admitted to dyspareunia. Dyspareunia is usually felt during intercourse, particularly in any coital position that facilitates deep penetration. The pain is usually fairly localised and can be quite severe, especially in patients with deposits in the recto-vaginal septum and uterosacral ligaments, to the point that most women will cry out and suggest a change of position and in some women the pain is so severe that they avoid intercourse altogether. This can cause considerable psychological problems within a marriage and is particularly the case if the couple are trying for a pregnancy. The pain changes in nature after intercourse and is often described as a dull ache which can last for a few minutes to several hours but it is rare, in my experience, for patients to have pain the following day. This is by no means a hard and fast rule and certainly some patients with endometriosis can suffer discomfort the following day, but usually these patients have associated venous congestion as part of the pelvic congestion syndrome (2) and occasionally these conditions can co-exist or be found separately at the time of diagnostic laparoscopy. In his excellent text book “The Principles of Gynaecology”, Sir Norman Jeffcoate drew attention to a type of dyspareunia ‘which is not uncommon, in which the patient describes abdominal and pelvic discomfort as occurring hours after coitus, often the next day. The cause of this is always psychological; the patient is providing an excuse to avoid coitus – she may even be bored with it. The mechanism of the pain is usually colonic spasm, but may occasionally be uterine contractions’. (3) The pelvic congestion syndrome is a distinct clinical entity which is difficult to treat. Typically there is pelvic pain of variable intensity which is worse pre-menstrually and greatly increased by fatigue, standing and especially coitus. The pain associated with coitus (dyspareunia) leads to anxiety and often frigidity and marital disharmony. Bladder irritability, presenting as urgency rather than frequency, is often present due to varicosities in the region of the trigone. The condition is extremely difficult to treat and although psychotherapy is helpful, these patients often end up having a hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy which will provide relief, because the veins are essentially draining the uterus. If the venous congestion is mainly involving the ovaries, success has been reported by venous embolisation of the ovarian and/or internal iliac veins (4) or, by extra-peritoneal resection or ligation of the ovarian veins. (5,6) These patient constitute a difficult group of patients to treat. They often have high levels of anxiety, depression, anger or hostility, somatisation and altered family roles than those in controlled groups. (7) They often have psychological disturbances and, in many instances, a history of physical or sexual abuse. (8) The diagnosis can be confirmed by transvaginal ultrasound with colour Doppler or by pelvic venography. Pelvic varicosities are usually obvious at laparoscopy, particularly if the pelvic sidewalls are examined with the patient flat or with the head raised and a probe used to displace the bowel from the pelvis. Uterine retroversion A retroverted uterus can cause deep dyspareunia, particularly in the presence of adenomyosis or an adenomyotic nodule in the upper posterior wall, which is then in direct relation with the posterior fornix. The altered position of the ovaries in uterine retroversion can also cause discomfort during intercourse and the pre-operative use of a Hodge pessary to antevert the uterus is recommended as a diagnostic test before operative correction by laparoscopic ventrosuspension (9) or laparoscopic plication and suspension of the round ligament. (10) Such operations can be extremely uncomfortable for a few days postoperatively and great care must be taken to avoid distorting the course of the fallopian tube. Laparoscopic ventrosuspension appears to be performed less often nowadays, although relief of deep dyspareunia can be very dramatic and Raslin et al (11) reported reduction of deep dyspareunia in 81% of patients at least one year after operation. Deep infiltrating endometriosis (adenomyosis) Probably the commonest reason for deep dyspareunia in young women is the presence of deep infiltrating endometriosis in the rectovaginal septum and in the uterosacral ligaments. In our department we use the CO2 laser via the laparoscope and the colposcope to vaporise the adenomyotic nodules and the associated fibromuscular hyperplasia. This is associated with a 70% reduction in dyspareunia and this problem is dealt with in the previous paper “Can surgery relieve pain and sexual activity?” (vide supra). References 1 O’Connor D.T. Clinical features and diagnosis of endometriosis in: O’Connor (Eds) Endometriosis. Ch.5 pp 68-84. Churchill Livingstone, London 2 Beard R.W. Chronic pelvic pain. Br. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1998; 105 : 8-10 3 Jeffcoate T.N.A. (1967) Problems of sex and marriage. In: Principles of Gynaecology (3rd Edition) Chapter 37 p 733. Butterworths, London 4 Venbrux A.C. and Lambert D.L. Embolisation of the ovarian veins as a treatment for patients with chronic pelvic pain caused by pelvic venous incompitence (pelvic congestion syndrome) In: Sutton C. (Ed) Endoscopic Surgery. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 11; 4:395-399. 1999 Lippincot, Williams and Wilkins, London, UK 5 Rundqvist E. Sandholm L.E., Larsson G. Treatment of pelvic varicosities causing lower abdominal pain with extraperitoneal resection of the left ovarian vein. Ann. Chir. Gynaecol. 1984; 73: 339-341 6 Hobbs J.T. The pelvic congestion syndrome. Br.J.Hosp.Med. 1990; 43:200206 7 Reiter R.C. A profile of women with chronic pelvic pain. Clin.Obstet.Gynaecol. 1990; 33: 130-6 Walling M.K. Reiter R.C., O’Hara M.W., Milburn A.K. Lilly G., Vincent S.D. Abuse history and chronic pain in women. 1: Prevalences of sexual abuse and physical abuse. Obstet. Gynaecol. 1994; 84: 193-9 8 9 Gomel V. Taylor P.J. Uterine displacement In: Gomel V., Taylor P.J. (Eds) Diagnostic and operative laparoscopy. St. Louis; Mosby, 1995: 299-308 10 Batioglu S., Zeyneloglu H.B. Laparoscopic plication and suspension of the round ligament for chronic pelvic pain and dyspareunia. JAAGL. 2000. 7 (4): 547-51 11 Raslan S., Lynch C.B., Rix J. Symptoms relieved by endoscopic ventrosuspension. Gynaecol. Endosc. 1995; 4: 101-4